In our previous post, we looked at the networked coalition of players who must be engaged in city-wide efforts to address the water and sanitation challenges that plague India’s slums. Here, we look at how the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation has begun to apply a well-known tool, systems mapping, to 1) help evaluate which cities are ready for city-wide change and 2) identify how we can best apply our resources to support those who must be involved in any successful effort to bring about sustainable city-wide improvements.

In Ahmedabad, foundation grants to the Mahila Housing Trust (MHT) supported the provision of water, sewage, and toilet connections for thousands of families living in 35 slums. The focus of the grant was to help MHT engage with local government, educate community members about the need for basic services and build demand, and establish microfinance support for families interested in obtaining loans to access water and sanitation services in their homes. A few years after the facilities were constructed, customer satisfaction surveys suggest that usage continued to be high (more than 80 percent). An impact study (which included a different sample set than the survey) showed that incidence of water-related diseases—including typhoid, jaundice, diarrhea, cholera, malaria, and other stomach problems—had decreased by more than 50 percent in slums where households received both water and sewage connections.

While successful, this effort was predictably complex. Delays in approvals, lack of space, intra-slum politics, and inadequate government support were among the hurdles we had to confront to achieve any kind of success. These hurdles and the lessons we learned along the way led us to ask: Did we have to reinvent the wheel for every water-sanitation project we considered? The short answer was no. We could adapt systems-mapping as a reusable (and flexible) tool to help us identify and select cities that have the capacity—across a range of critical actors—to achieve city-wide implementation and adoption of water and sanitation services.

A 2009 paper, “Unique Methods in Advocacy Evaluation” by Julia Coffman and Ehren Reed, describes systems mapping as a valuable tool for evaluating efforts to change systems: “System maps offer a useful alternative to most conventional theories of change and logic models … which tend to be linear and have difficulty capturing intended changes in relationships or connections in a complex system.”

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

As an exercise, creating a systems map involves the creation of a literal, visual map that identifies the parts and relationships in a system. The map highlights what may change, documents expected changes, and identifies “ways of measuring or capturing whether those changes have occurred.” This approach is particularly useful for mapping complex ecosystems that are made up of multiple organizational networks, diverse physical and social environments, and individuals who inhabit the identified ecosystem. In one well-documented example, the Innovation Network used systems mapping to evaluate the international aid organization CARE and recommend more effective ways for the organization to reach the US government with its advocacy efforts.

In practice at the foundation, systems maps help us understand, before we engage in a project, how relevant organizations in a given city or—in the case of our work in water and sanitation in urban India, slum—work and interact. Our systems maps document:

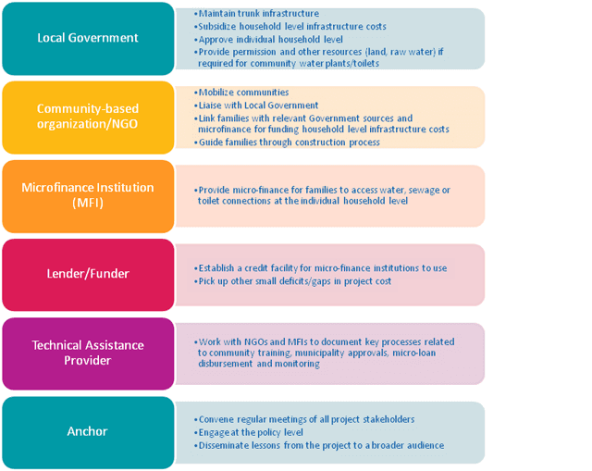

- The roles and responsibilities of key organizations that affect the success of a project and that can influence particular types of outcomes (see figure below). These include local government, participating families, microfinance institutions, community-based organizations, technical assistance organizations, and others.

- The implicit and explicit relationships among organizations that must participate to ensure project success.

- The functional strength of each key organization. Water sanitation projects in urban India require a consortium comprising stakeholders who coalesce into an organizational network that will implement the effort citywide.

- Environmental considerations, including: the type of job available to most slum residents, which may range from day laborer to shop keeper; existing infrastructure; construction limitations that may affect how a given project is engineered; and legal status of slums (many in urban India are illegal; others are officially recognized as legal residences).

The roles and responsibilities of stakeholders who are likely to affect the success of a citywide water sanitation effort.

The roles and responsibilities of stakeholders who are likely to affect the success of a citywide water sanitation effort.

The ability to view each component of a systems map in conjunction with the others offers a layer of discipline that guides our funding. For instance, if the majority of slums in a city are not legally recognized, we know that household level infrastructure improvements may be unworkable, because 1) it is unlikely that the slums have pipelines, and 2) government will not approve individual household connections. In these “illegal” slums, community-level solutions that include a clear maintenance plan are likely the best solution.

Alternately, some local governments have little money set aside to support the urban poor. Supposing that most families live in recognized slums and want to construct individual toilets, then we can assess a bigger role for microfinance and move to the next step: evaluating families’ capacity to qualify for and manage microloans.

By tailoring the support we provide, we avoid the inevitable pitfalls of superimposing a “one size fits all” approach that doesn’t match the needs of individual communities.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Urvashi Prasad & Semonti Basu.