(Illustration by Sandra Dionisi)

(Illustration by Sandra Dionisi)

In the fall of 1988, there was an unusual changing of the guard in the world of philanthropy, with three new people stepping into CEO positions at big foundations—Rebecca Rimel at the Pew Charitable Trusts, Adele Simmons at the MacArthur Foundation, and Peter Goldmark at the Rockefeller Foundation. These leaders wanted to bring their collective resources to bear on tough issues. They selected energy as one of their focus areas. None of the foundations had an energy program, but after much discussion, the three leaders decided to do something radical and create a foundation whose sole mission would be to help the world meet its energy challenges.

The Power of Philanthropic Partnerships

This special supplement looks closely at the lessons the Orfalea Fund has learned about how to create effective partnerships with nonprofits, government agencies, and other philanthropies.

-

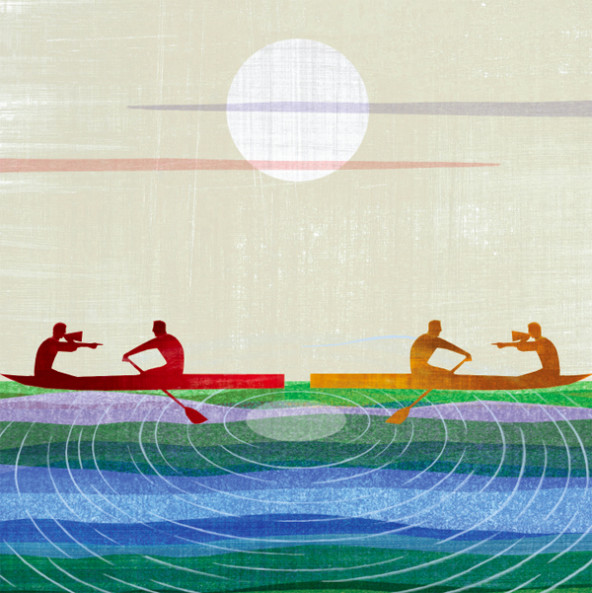

“Where Two Rivers Meet, The Water Is Never Calm”

-

Migrating a Partnership Ethos

-

The Pillars of Partnership

-

Accepting the Challenges of Partnership

-

Valuing Stakeholders in Early Childhood Education

-

Early Lessons Propel a Movement

-

Building Disaster-Ready Philanthropy

-

Strengthening Santa Barbara County’s Disaster Resilience

-

Choosing the Right Partners for School Food Reform

-

A Changing Landscape for School Food

-

Lessons From a Sunsetting Fund

-

When to Lead, Follow, and Let Go

-

The Gates of Hope

This was an ambitious move for three major institutions with very different cultures. At that time, there were no roadmaps to guide partnerships or collaborative relationships for philanthropic ventures. And yet, some 27 years later, 13 other major foundations have joined the partnership; it is still going strong. There are many more such stories, both national and local. But the path to successful partnerships is also littered with many attempts that have failed. Even today, with a growing body of experience as our guide, joining forces to make a difference is not an easy prospect.

A Difficult Learning Experience

At The Orfalea Fund we have had many successes, but our partnerships did not always succeed. For example, consider one of our School Food Initiative’s investment areas: School Gardens. Research demonstrates that children participating in school garden programs are motivated to consume more fruits and vegetables, can identify more vegetables, and often develop preferences for eating a variety of vegetables. Motivated by those findings, the fund partnered with a community college to build and maintain 35 gardens in six school districts, and to support educators in using the gardens to enhance students’ learning experiences. With the assistance of garden education managers (GEMs), lead teachers, and parent volunteers, the gardens would serve as an outdoor classroom in which children reconnect with their food and learn about biological processes, community building, and cooperation.

The concept was strong, but several challenges soon emerged. We struggled with hiring practices, overhead costs, and staff turnover. We knew that hiring part-time GEMs with a restricted maximum hourly wage would limit our applicant pool, but we also knew that growing the number of program employees would increase overhead costs and jeopardize the initiative’s sustainability. Additionally, we faced pushback from our partner because food literacy did not fit easily into its STEM-focused curriculum, and we received minimal buy-in from schools and school districts because the program was to be operated by an independent partner with direct funding support. We were not aligned with our partner on how to approach problem solving, and we were unable to leverage the strengths on both sides of the partnership to overcome our challenges.

The dissolution of that partnership was one of our greatest lessons. In hindsight, we realized that the fund had inadvertently created reliance on our funding support, and when the program became unwieldy, we had pressured our partner to think differently—admittedly, to think like us—in solving problems. It was an untenable situation, so we sought a new partner. The School Gardens program is now led by another local partner, and has been restructured to eliminate inefficiencies and maximize impact with the direct engagement and support of schools and school districts.

It seems clear now that, from the beginning, our expectations regarding the goals, roles, processes, and responsibilities of partnership differed from those of our original partner. We had not aligned our standards and values, and so we became uncomfortable in our day-to-day interactions. It was an agonizing experience, and we knew that we needed to avoid repeating those errors. So we took the time to reflect deeply on the process of partnership, to see if we could determine how to position ourselves to be consistently productive collaborators.

We determined that there are at least three distinct phases of partnership and collaboration: initiating the partnership; developing the partnership; and maintaining and sustaining the partnership over time (or implementing an exit strategy). Each phase generates opportunities for disciplined rules of engagement that lay a strong foundation for a successful partnership. The fund’s Six Pillars of Strategic Partnership were codified after a handful of particularly challenging partnerships, but are based on lessons from the most productive experiences of our first decade.

Initiating Partnerships

Those who initiate a partnership need to be clear on what the goal will be and why a collaborative effort will lead to outcomes that might otherwise be unattainable. Then these parties must tackle an array of tough questions: Should it include other funders? Which nonprofits, educational institutions, NGOs, or government agencies ought to be involved? What qualities do participants need? What are the potential deal breakers? What “red flag” threats would rule out a potential partner, or signal that a partner would need to be monitored?

The initiators also need to be careful when identifying and approaching partners. Early in our experience, we fell into partnerships organically, but as we gained experience we learned to be more deliberate. We started to think further ahead. In addition to defining goals and providing financial support, funders may build or provide conceptual frameworks, identify and convene key local actors, establish ground rules for action, define success, and put in place a way to monitor and assess progress. But then what? The Orfalea Family Foundation began convening directors of Early Childhood Education (ECE) Centers in 2001, managing every aspect of an annual multi-day retreat. But we knew that our goal was to create something that would ultimately take off on its own. Now, with intentionally diminished support from The Orfalea Fund, the ECE sector runs its own council, facilitating learning sessions and tours, and identifying and sharing best practices among its members. When the fund sunsets, the now self-sufficient partners will continue to advance the goals we agreed on long ago.

In cases where partnerships are initiated and driven primarily by nonprofit groups and community leaders, foundations may find that their most important contribution is flexible funding to help launch, sustain, and evaluate the effort. Funders may also be uniquely valuable to a partnership for their contacts and relationships—additional resources that can support the partnership in different ways over time.

Developing Partnerships

Effective collaborations start with a discussion about values and mission statements, and agreement on operating principles that will govern and guide the work. In those early talks, it is helpful to cover topics such as: ground rules for discussions, planning, and decision making; metrics for the ongoing assessment of progress; and planning for the inevitable unintended consequences and “unknown unknowns.” Partnerships involving community-based nonprofits should also cover the balance of power between funder, grantees, and the community being served. A commitment to the principle of “deep listening” encourages better ideas and fewer surprises.

Potential partners also need to explore various types of collaborative structures in order to ensure effective leadership, and in some cases they need to provide for (or allow) different types of leadership at different levels of the partnership or network. The structural planning exercises we have found most helpful include: documenting each partner’s conditions, needs, assets, and strengths; developing a process that ensures active engagement; and identifying resource needs to support planning, implementation, evaluation, and other elements. If partners don’t pay attention to those kinds of specifics up front, relationships are likely to become unnecessarily strained. This is what occurred in our partnership with School Gardens. The Orfalea team believed that food literacy should anchor the curriculum, while our partner believed it should be STEM. The stalemate on this point strained our relationship and ability to resolve other issues.

Maintaining and Sustaining Partnerships

Designing a partnership carefully can provide the solid framework necessary for an effective ongoing collaborative effort, but design alone does not suffice. Several additional elements are also important: ensuring that all participants have a legitimate voice; creating a comprehensive plan of action that all parties embrace broadly and deeply; committing to reviewing—and meeting—evolving leadership needs; committing to reviewing and reworking partner roles as needed; and identifying appropriate metrics to measure progress, improve, and capture evidence of concrete success.

Most of all, though, partners must be resilient in the face of inherent tensions and inevitable conflict. Establishing clear rules of engagement does not eliminate the conflict inherent in a relationship, but doing so will mitigate the most damaging effects and help build trust. Your partner will frustrate you. You will frustrate your partner. Your partner will let you down. You will let your partner down. Accept the challenges of partnership because together you are stronger, together you are smarter, together you are deeper and wider. Together, you have a much better chance of achieving your goals. Where two rivers meet, the water is never calm. But doesn’t philanthropy stir things up to enhance and improve life for everybody?

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Lois Mitchell & Peter Karoff.