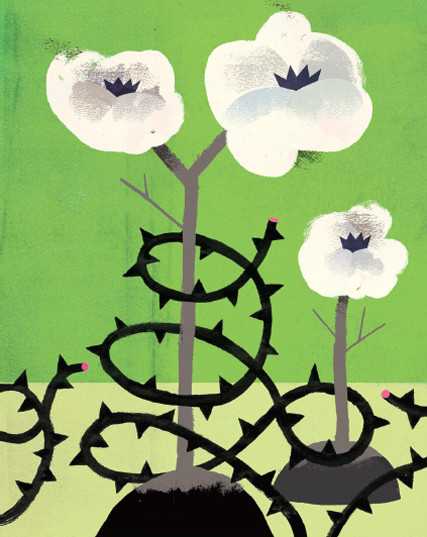

(Illustration by Justin Gabbard)

(Illustration by Justin Gabbard)

“The hardest part is reopening the land,” says Stella Atimango, an agricultural extension worker standing in a former battle zone beside neat rows of recently planted cotton on a one-acre farm in northern Uganda. Beyond Atimango, the tiny cotton field was surrounded by an abandoned countryside, the result of two decades of fighting between the Ugandan military and the Lord’s Resistance Army. Today, smallholder farmers use hand hoes and oxen to reclaim their land. The famine in East Africa is lending even greater urgency to Atimango’s work.

“Once the land is cleared,” she adds, “our elders take the lead because their sons and daughters grew up in the refugee camps and don’t even know what farming is, much less growing cotton. The older ones—their backs are weaker, but they remember how to be farmers.”

Small-scale cotton growers are rebuilding northern Uganda after years of bloodshed and brutality in one of Africa’s longest-running civil conflicts. As founder and CEO of the nonprofit agricultural lender Root Capital, I traveled to Uganda recently to visit our clients and to witness for myself the intersection of Root Capital’s work with post-conflict reconstruction—an issue of vital importance to our clients in northern Uganda and many countries in Africa and Latin America.

In preparation for the trip, I read about the growing consensus among scholars and policymakers that a strong link exists between economic impoverishment and conflict. In countries from Rwanda to Liberia, both absolute poverty and intergroup inequality contribute to the incidence of conflict. Fortunately, policymakers and practitioners are beginning to realize that the converse also appears to be true: Economic reconstruction can help consolidate peace after war; and in rural areas in particular, investment in agriculture is a post-conflict necessity. A 2009 UN report found that “in many rural areas reestablishing agriculture can represent one of the best opportunities for absorbing target groups, for strengthening household incomes and food security, and for stimulating economic growth in post-conflict areas.”

From Colombia to the Ivory Coast and South Sudan, economic development plays a vital role in consolidating the transition to peace and security in two ways—by absorbing former combatants into other activities, and by reducing support for violence as ordinary people experience improvement in their material lives. Root Capital has seen in countries such as Rwanda that working together at a coffee washing station can reduce tensions between former combatants, reinforcing the positive effects of other reconciliation initiatives.

The agricultural sector plays a particularly important role in reconstruction. Because the majority of people in many post-conflict countries are agriculturalists and because the industrial base takes longer and requires more capital and infrastructure to rebuild, agriculture is the only sector that can rapidly absorb large amounts of labor and rebuild household economies.

Yet, in spite of the crucial role economic development plays in stabilizing conflict-prone societies and supporting peaceful transitions, it is precisely in these situations that private sector investment is missing. Data show that foreign private investment generally waits a decade before entering countries recovering from internal strife—not coincidentally, the same period that is most crucial for ensuring a lasting peace. Private investors are understandably wary of risking their capital on enterprises that combine the risks of agriculture with the risks of post-conflict settings.

Perhaps more surprising is the paucity of development assistance dedicated to rehabilitating the agricultural sector in post-conflict countries. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization found in its 2010 “State of Food Insecurity” report that “agriculture accounts for a third of protracted crisis countries’ gross domestic product and two-thirds of their employment. Yet agriculture accounts for only 4 percent of humanitarian ODA [official development assistance] received by countries in protracted crisis and 3 percent of development ODA.”

Meanwhile, fully 40 percent of armed conflicts that end in a negotiated settlement revert to violence within 10 years. From where will the investment come that’s so desperately needed to mend broken societies and prevent old wounds from reopening?

TOWARD ECONOMIC REVIVAL

Despite a tiring day of travel in a bouncy truck, I couldn’t sleep our first night in northern Uganda. We had driven across the Nile River earlier that day, heading north from Kampala toward the border with South Sudan and stopping in cotton country in the Gulu District. The area is currently recovering from nearly 25 years of armed conflict that left it the poorest region in Uganda, with a poverty rate of 61 percent that’s twice the national level.

Root Capital began working in Uganda five years ago, and we have since financed and trained a dozen rural enterprises that are improving livelihoods for one-acre farmers of everything from coffee and cocoa to vanilla and chili peppers. But in the north, we began lending only in the fall of 2010 to cotton farmers in Gulu District.

Three years ago, internally displaced farmers in Gulu and the neighboring Acholi District began returning to their land, only to discover their huts burned and destroyed, livestock killed, and farm tools gone. Although cotton had once been the economic mainstay of the region, the fighting had shuttered the only ginnery in Gulu for a decade.

In 2009, the Gulu Agricultural Development Company (GADC), a cotton ginner and exporter based in the town of Gulu, rented and rehabilitated the ginnery and began trading on a limited scale. In December 2010, GADC came to Root Capital and Acumen Fund, another social financier, for a loan when local banks couldn’t provide adequate financing. The joint facility of $1.4 million enabled GADC to reach its target of quadrupling its production from the 2009-10 harvest to 2010-11.

Within two years, GADC has become an anchor of the region’s economic revival, allowing 25,000 farmers to access seeds and connecting them to a secure market. The company also has a transition program through which farmers receive organic training from agronomists like Atimango on crop rotation and soil fertility management, as well as simple tools and tree seedlings for reforestation.

Two hours outside the town of Gulu, down red dirt roads lined by recently cleared fields, Atimango provides extension services for the organic cotton program of GADC. She is one of the agronomists working in the countryside with about 3,500 farmers in transition to certified organic cotton.

Young or old, many farmers still fear the possibility of renewed violence, and so not all are ready to build a permanent home. Although they continue to live in makeshift huts, the farmers are succeeding with cotton. With the world price of cotton at all-time highs during the 2010-11 season, cotton farmers with access to the direct export market earned prices more than four times those for maize. One young man we met used his cotton proceeds to buy a bull and a bicycle and build a new hut with a concrete floor. These kinds of returns are attracting young adults who grew up in the camps and are now farming their own fields for the first time.

An irony of the war is that, having been left fallow for so long, land here is productive and the conditions for organic farming are near ideal. In eastern Uganda, where cotton has been intensively cultivated for years, overfertilization and overuse of chemical pesticides have mined soils of nutrients and harmed beneficial insects and soil microorganisms. By contrast, Gulu District’s abandoned farmland became more fertile and still has “friendly pests,” such as black ants and wasps, available biomass for mulching, and lots of space between fields to protect organic farms from conventional agrochemical pollution.

GADC is training farmers to preserve these natural advantages; for example, by planting “trap” crops to attract insects away from the cotton, producing natural insecticides from local plant species, and conducting pest counts to determine whether to spray.

“Who wants to go to the hospital when you are not sick?” says William “Willy” Okumu, 49, a farmer who has adopted the practice of spraying only when necessary. Okumu, wearing a threadbare shirt reading “World Water Day,” was weeding his cotton field with a well-used hand hoe when we met. He lived in a refugee camp from 1996 until 2007.

Today, Okumu belongs to the Panyabono Organic Farmers Association, and he’s a lead farmer of a group of 300 members, all of whom joined together to sell traceable, organically certified product to GADC. Having started in cotton last year, he prepared the soil on another acre of land in April and planted cotton in June that was picked in January. In March and April of this year, he will plant other food crops that are grown in rotation with cotton, including leguminous beans that help fix nitrogen in the soil. With proceeds from last year’s cotton harvest, he bought his second son an ox plow to prepare his own land and hire it out to neighbors. Okumu’s cotton sales also paid for his second son to attend a medical college. “A few years back, virtually every school in the district was empty,” he said, noting that most of the farmers in his group can now afford school fees to send at least some of their children back to school.

Then there are Richard and Enin Wilobo, a couple who returned to their family home in 2009 after four years in a refugee camp, only to find their house burned to the ground and their few assets—mainly livestock and tools—gone. Richard has since rebuilt a hut and moved in with his wife and six children, whom he supports with income from selling his cotton crop. He said that living in the camp was hard, but that mainly he was happy to be back on his land with his whole family intact. For Richard and his neighbors, this is the peace dividend.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by William Foote.