In December 2013 my organization, the Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO), became one of the first nonprofits to launch a Pay for Success (PFS) project in the United States. In this four-year, $13.5 million transaction, CEO will serve high-risk men recently released from prison and returning home to New York City and Rochester, New York. The intervention will provide 2,000 individuals with a program that CEO has proven, through outside evaluation, reduces recidivism. If individuals in the treatment group spend at least 8 percent fewer days in jail or prison than the control group, and show at least a 5 percent increase in their immediate and long-term employment, the federal government and the State of New York will return investors a portion of the savings. Returns for the 44 private investors financing the project can reach as high as 12.5 percent. However, if these targets are not met, investors stand to lose their capital.

At its core, this is a performance-based contract. But instead of focusing on outputs like job placements, it hinges on our organization making an impact on recidivism and long-term employment. And while CEO has experience with performance-based contracts, in size, scope, and complexity, this project is like no other we have taken on in the past. To finalize the project design and contract, we worked closely with the intermediary Social Finance and New York State for more than a year. Mutual interest in the project’s success drove trust and collaboration between all parties. But as the provider, there was no playbook, road map or learning community to guide us through the intricacies of scoping this project or bringing the deal to closure.

The opportunity for CEO is significant: receive unrestricted capital to deliver our core program to the population for whom we make the deepest impact. There are risks. Random assignment evaluation, scaling up, and multi-year, multi-million dollar contracts all require significant preparation and due diligence for nonprofits. Additionally, we had to quickly become familiar with the language and priorities of the investment community. Terms such as “asset class” and “capital stack” were new to our lexicon.

PFS opportunities will continue to have a strong allure for nonprofits into the foreseeable future. Untapped capital, contracts that pay the real cost of services, and the chance to be on the cutting edge of innovation are just some of the attractions. Yet, given the nascent state of the field, there are few deals for nonprofits to use as models. As Tracy Palandjian, co-founder and CEO of Social Finance, has said, “If you have seen one Pay for Success deal, you have seen only one Pay for Success deal.”

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

There has been plenty written about how the impact investing community assesses risk in this emerging marketplace, but precious little on how the recipients of this investment—in most cases, nonprofit providers—should assess risk. Risk comes in two forms here: reputational and financial. These projects are highly visible; failing on center stage could be damaging to an organization’s future, and some deals may ask for a nonprofit’s financial involvement, which presents a whole other type of risk.

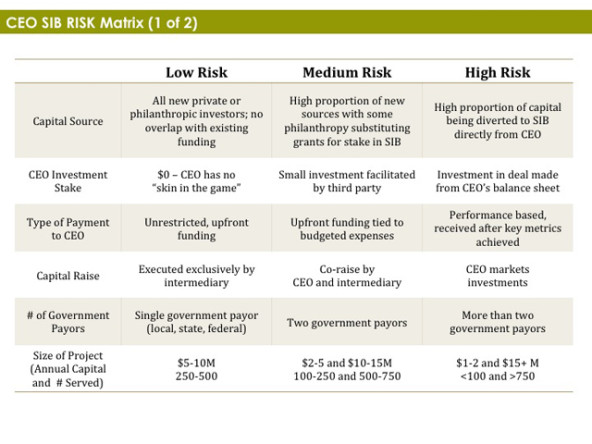

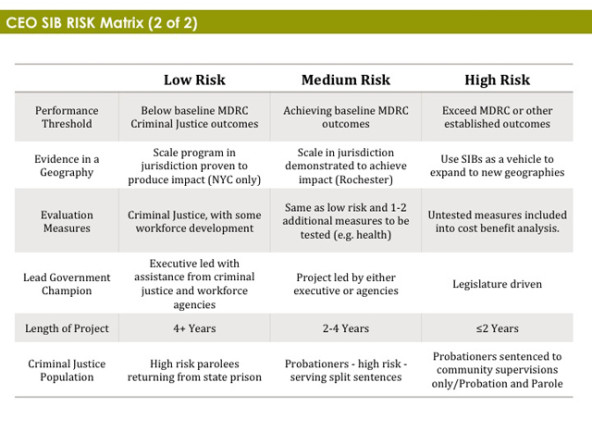

Drawing on our experience in the New York State transaction and early due diligence on a potential project in San Diego County, I have drafted a matrix that can help nonprofits assess the risks in both closing deals and operationalizing projects. Some elements in the matrix will be widely applicable, others specific to CEO. I hope that, where it is specific, there will be ready analogs that practitioners in other fields can swap in based on their own work.

Let me first explain the structure of the matrix. I have selected 12 “deal components” and provided low, medium, and high-risk scenarios.

A few important points before diving in:

- Risk does not correlate to reward. In some cases, the lowest-risk option provides the most benefit and the highest risk the least benefit.

- There are deal breakers. Some of the high- and even medium-risk scenarios are options that would preclude us from participating in a deal. There are places here where CEO wouldn’t go past low risk, other areas where we would take on more risk.

While 12 deal components are included in the matrix, I have selected five below to detail more extensively.

Let’s start at the top with Capital Source. Here we are asking: Who are the investors in the deal? This matters. One of our interests in participating in a PFS project was accessing new forms of financial support that were previously unavailable to CEO. A high-risk scenario would be if existing government and/or philanthropic support were diverted into a PFS deal. We are loathe to cannibalize existing funders. The low-risk option was attracting entirely new capital to participate in the deal. In future deals, I could envision CEO accepting the medium-risk scenario, but for our first deal, it would have been a deal-breaker to go past the low-risk scenario.

CEO Investment Stake: In the New York deal, CEO has no “skin in the game.” We are not an investor. CEO will not share in the windfall if we hit all of our performance thresholds and the investors get their full return. The organization has no direct financial risk. Instead, we will get paid, up front, for each person who enrolls in the project. Other nonprofits have gone in a different direction and have found funding for their stake in the deals. This was not viable for CEO. We wanted to put our organizational emphasis on planning and running the project with excellence and believed that simultaneously raising a substantial investment would interfere. What’s more, we did not feel our reserve could cover our stake if we were not successful in the capital raise. If a third party facilitated our investment (medium risk) or our balance sheet condition improved dramatically (high risk), we would not rule out those options, but these scenarios currently are not viable options.

Number of Government Payors: This component addresses the risk of deal closing. PFS projects are complicated enough for just one government entity to wrap their minds around, let alone multiple entities. That said, the work that CEO and other providers perform frequently saves government money across local, state and federal levels. Jail savings, prison savings, and Medicaid savings? It’s likely that we produce them all. The reward of coordinating across these systems would be significant but could present the greatest risk in getting to closure. The varying legal and procurement requirements—not to mention underlying motivations—can make the most ambitious projects higher risk. In CEO’s case, we have both federal Department of Labor and New York State support, which would have put us in the medium-risk category for deal closure. Having both parties in the deal allowed us to extend the project from two to four years.

Evidence in Geography: In this domain, CEO was comfortable in the medium-risk scenario. For the New York deal, we are implementing this project in our New York City office, which has already been subject to random assignment evaluation. But we are also including Rochester, New York, which has not been subject to a similarly rigorous evaluation. We were comfortable with this scenario, because only 15 percent of the treatment group participants will be from Rochester and in preparation for the deal we were able to perform a comparison group analysis that showed the Rochester office was performing at a level consistent with CEO’s previous evaluation. Moving forward, there is a possibility that CEO could take on the high-risk option of using PFS to scale into new geographies, but there would have to be a 12-18 month start-up period to ensure that program fidelity was achieved in advance of beginning the project.

CEO generally selected options in the low- to medium-risk categories, but we did so as they arose. My intent here is to begin a conversation amongst providers, intermediaries, government, and investors in which the risk/opportunity calculus for the nonprofits is integrated into the deal-making process. This matrix is just a starting point. To make tools like this fully functional, we will need to:

- Add additional components. By no means are the 12 I selected exhaustive. We will need a more extensive listing, divided by “risk for closure” and “risk for operationalizing.”

- Refine by geography and issue area. Providers in early-childhood, health care, and other arenas will have to consider whether these components are too narrow or broad for them to use effectively. Providers working in other states will need to add geographic-specific components

- Develop risk score and proportional weighting. If our efforts in adding and refining the matrix are successful, this tool could become a scoring mechanism to determine whether nonprofits should or should not enter into a PFS deal. For that to happen, we will need to develop a system for assigning weight to individual components and more clearly assigning “deal-breaker” status for those that present untenable risk.

PFS projects have the opportunity to fundamentally change how government works by placing an emphasis on funding high-performing, evidence-based practices. The field will have to scale, and more providers and projects will need to enter the marketplace. As more nonprofits enter this space, it is imperative that they have tools to fully assess the risks and rewards of this new, exciting financing mechanism.

Download a PDF of the matrix here.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Sam Schaeffer.