In October 2014, the nonprofit news organization ProPublica released “Deadly Force, in Black and White,” a study of police killings of civilians in the United States. By examining data collected by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation between 2010 and 2012, ProPublica found that young black men were 21 times more likely to be killed by police than were young white men. In most cases, white policemen were responsible for the killings. The average age of the black victims was 30. Police reports typically cited “resisting arrest” or “fleeing arrest” as the reason for such shootings. Often, however, the police didn’t provide a reason and instead described the circumstances of a given shooting as “undetermined.”1

Complete with graphics and links to official documents, “Deadly Force, in Black and White” is a great piece of original journalism. Media outlets quoted it, and civil rights organizations cited it in support of police reform. But in November, just a month after ProPublica released the report, an event occurred that highlighted the limited ability of media coverage to affect facts on the ground: A grand jury in Ferguson, Mo., declined to indict police officer Darren Wilson in the shooting of an unarmed black man named Michael Brown. When it comes to changing the world, it seems, powerful forces such as systemic racism often matter more than careful reporting and hard data.

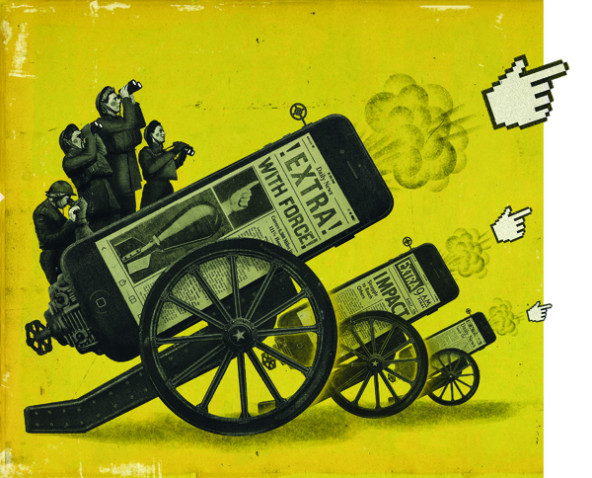

(Illustration by Curt Merlo)

(Illustration by Curt Merlo)

ProPublica, like a growing number of other media organizations today, relies extensively on donor funding to support its work. As a consequence, these media outlets face increasing pressure to demonstrate that journalism can make a difference in the world. Donors are seeking ways to measure the impact of the media projects that they fund, and media organizations in turn are working to track the real-world effects of what they publish—partly in the hope that proving their worth will help enable their survival.

The days when media companies could survive by relying solely on advertising and subscription revenues are over. Disruptive technologies, among other factors, have steadily eroded the business models that traditionally supported US news organizations. One alternative source of funding, of course, is the public sector. But Americans have always been uneasy with government support for media. The United States—unlike Germany and the United Kingdom, for example—has never developed robust taxpayer-supported public media institutions. In the absence of both commercial and public sources of revenue, more and more media organizations are willing to accept novel funding arrangements from the philanthropic sector.

Private philanthropy, along with government agencies, has long supported struggling newspapers and community radio stations in developing countries. Donors in this category include the Ford Foundation, the Open Society Foundations, the US Agency for International Development (USAID), and a host of European governments and international aid organizations. USAID, for example, has funded community radio stations in Mali, and the Open Society Foundations has supported media initiatives led by Burmese exiles.

But we are now adjusting to a reality in which major US and European news organizations depend on philanthropy. The Guardian newspaper receives funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for its Global Development Web page, and NPR gets support from that foundation for its coverage of topics such as education. In addition, as traditional media outlets cut their investigative budgets, donor-supported organizations like the Center for Public Integrity, the Global Investigative Journalism Network, ProPublica, and SCOOP have emerged to fill that gap. Philanthropic organizations, in fact, have fueled an explosion of independent investigative reporting in recent years. The Omidyar Network, for instance, has funded a Web-based outlet called Sahara Reporters, which focuses on exposing corruption in Nigeria.

Some of the most influential new donors on the scene today—including the founders of the Gates and Omidyar philanthropies—come not from a journalism background but from a business tradition in which management by metrics is commonplace. Partly under their influence, a movement has emerged to find ways to track the effects of donor-supported journalism. All around the world, media outlets are learning that some funders are uncomfortable with supporting journalism merely as a “public good.” They want to see proof of impact.

The Media Metrics Quandary

The task of “proving impact” doesn’t come naturally to most journalists. They reject a utilitarian view of their worth, preferring to believe that news is a public good that merits support for its own sake. They view themselves not as campaigners for a cause but as fair and impartial observers. At the same time, they like to think that they can change the world simply by “getting the story out.” Aron Pilhofer, executive editor of digital at The Guardian, summarized the prevailing view in a much-quoted blog post: “The metrics newsrooms have traditionally used tended to be fairly imprecise: Did a law change? Did the bad guy go to jail? Were dangers revealed? Were lives saved? Or least significant of all, did it win an award?”2 In any event, journalists tend to be wary of adopting universal metrics. They know that each media organization has a different audience that it wants to reach and different ideas about what constitutes “impact.”

There is skepticism on the donor side, too. Some donors have taken the stance that media impact is impossible to gauge: There are too many variables to measure, and the time scale for evaluation is too short, they argue. “Media organizations need to make the case that their work could lead to change, but I am very skeptical about what I see as a growing impact-industrial complex,” says one grantmaker from a prominent US foundation. The debate about whether and how to ask grantees to measure impact has created a fault line in the world of donors. In some ways, this dispute echoes the ongoing debate over strategic philanthropy. Here, too, critics argue that basing donor decisions on outcome-related evidence forces grantees to focus on conducting evaluations to prove the worth of their work—at the expense of actually doing that work.3

Journalists and donors both note that the media is only one part of a larger ecosystem. The multitude of variables that affect any process of social change makes it hard to isolate—let alone measure—the impact of journalistic efforts. People sometimes credit the media with helping to cement opposition to the Vietnam War, or with inspiring the protests that led to the Arab Spring, for example. But was it reporting on the Vietnam War that undermined public support for it, or was it the fact that middle-class college students didn’t want to fight in that conflict? Was the Arab Spring a “Facebook revolution,” or was it a predictable response to deteriorating economic conditions and widespread youth unemployment?

For years, economists and political scientists have studied the effects that media coverage has on areas such as government accountability, public corruption, and voting behavior.4 Their research shows that news coverage does affect a wide range of outcomes, including government spending decisions and governmental responses to natural disasters. At the same time, scholars warn that it’s hard to trace a direct connection between, say, a single newspaper story and an identifiable real-world effect. “If we were to monitor the effect of 100 news stories on people’s behavior and noticed no difference, we could conclude that there is no media impact. But then story 101 may cause people to take to the streets in protest. Perhaps that one story hit a nerve, or perhaps stories 99, 100, and 101 packed into a snowball that spurred the mobilization,” says Paul F. Lagunes, assistant professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University, who studies the effectiveness of anti-corruption programs. “Then there’s the question of unobserved change. A news story may modify the way we view the world without spurring us to take immediate action.”

What’s more, the metrics that media organizations typically use were not designed to measure social impact. Most of these metrics originated in the advertising industry. They estimate the size of an audience for broadcast and print outlets, or they count the number of visitors to a website. But knowing that an article reached millions of readers is only one part of answering the larger question of whether the article had an effect on voters and policymakers. After all, conveying information to a large number of people is not always the best way to promote social change. Minky Worden, director of global initiatives at Human Rights Watch, notes that efforts based on mass action often have limited efficacy. “Boycotts are kind of old-fashioned now,” she says. “Targeted sanctions, reaching policymakers at a key moment, or creative campaigns to change specific laws and policies can be more effective.”

Measure for Measure

Despite these concerns and caveats, several organizations are taking steps to develop usable standards for measuring media effects. Among those groups are the Gates Foundation, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Nieman Journalism Lab at Harvard University, the Norman Lear Center at the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, the Pew Research Center, and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. In looking at the approaches that these groups are adopting, we distinguish broadly between reach (how many people engage with a given body of media content), influence (how that content affects public dialogue), and impact (how the content helps drive policy change or movement building).

Reach | There’s no guarantee that a story read by millions of people will have more impact than one that reaches only a few hundred readers. But it’s easier to posit impact when a story finds a substantial audience. Numerous metrics exist to help news organizations gauge the audience for their content. In addition to the metrics commonly used by Web advertisers—page views, unique visitors, and so on—some outlets consider “attention minutes,” a variable that measures the amount of time that readers spend with an article or view. The leaders of Upworthy, a website that develops and markets articles that it deems “meaningful,” label attention minutes as their “primary metric.” More specifically, they look at two variables: “total attention on site” and “total attention per piece.”5 Many organizations also track the “social sharing” of a story by noting how often people cite it on Facebook, Twitter, and other social networks. Sharing of this kind expands the reach of a story beyond the base of a site’s regular readers.

One problem with focusing on reach is that it tends to favor offbeat or feel-good stories over more substantial reporting and analysis. Another problem is that reach-oriented metrics are ones that people can easily manipulate. If the number of clicks on a given article is the measure of its reach (and if advertising revenue derives from reach data), then those who manage websites will devise ways to increase that number. Hence the emergence of “clickbait” stories that carry attention-grabbing headlines and of “bots” that click on stories automatically.

Efforts to enable advanced approaches to measuring reach are now under way. A leading example is NewsLynx, a project hosted at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. NewsLynx aims to help news organizations and their funders map how stories spread across the Web. “We found that people were getting a bunch of notifications from Google Alert and then manually entering them into a spreadsheet. We are trying to make the drudge work of being an impact analyst easier,” says Brian Abelson, who helped launch NewsLynx. (For more information on that initiative, see “Reading Between the Lines.”)

Influence | How do media stories affect readers’ attitudes? How do they shape the public dialogue as a whole? We know that in some cases media coverage can change how people and organizations approach a given issue. Josh Greenberg, an associate professor of communication at Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario, studied the way that coverage of labor conditions in the shoe factories that supply Nike led to a change in how people think about solutions to the sweatshop problem. He showed that media outlets such as The Washington Post shifted their coverage away from the conditions in those factories and toward the role of individual buying choices. As a result, the discussion of how to solve the problem began to focus less on improving or enforcing regulations than on, say, encouraging consumers to buy fair labor footwear.6

In the past, news organizations had to rely on focus groups and survey research to understand how audiences absorbed their content. But with the rise of the Web, the toolkit for measuring influence has expanded dramatically. Hyperlinks, the glue of the Web, provide a clear proxy for influence. Media professionals sometimes claim that a link isn’t an endorsement. But there are clear indications that when an author links to a story, she signals that the story did influence her (positively or negatively) and that it therefore has helped shape the broader discussion of a given topic. Consider a study led by Yochai Benkler, a professor at Harvard Law School. Benkler and his colleagues used links to trace how Wikipedia contributors, grassroots activists, and technology bloggers influenced the debate over the Stop Online Piracy Act (also known as SOPA-PIPA), a bill in the US Congress that proposed significant changes to the laws that protect copyright holders on the Internet.7

Media Cloud, a joint project of the MIT Center for Civic Media and the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, offers a new way to discern patterns of influence. (One of us, Ethan Zuckerman, is a principal investigator for Media Cloud. So is Yochai Benkler.) It is an open source tool that monitors 50,000 social and journalistic channels, and it allows researchers to study two important media-based processes: agenda setting and framing. By measuring the volume of stories on a given topic, as compared with the coverage of other topics, Media Cloud can show how effective politicians, activists, and other parties are at putting an issue “on the agenda” for public debate. And by tracking the language that people use to talk about a topic, Media Cloud can highlight the various “frames” that get attached to a news event. A frame, in short, is a way of interpreting an event that supports one social or political agenda over another. A story about the killing of Michael Brown, for instance, might lead to discussions of topics such as urban poverty, racial bias, and militarized policing. By tracking published stories and clustering those that use similar language, Media Cloud helps identify which frames appear in reporting and which news outlets have introduced new frames into the public debate.

A difficult challenge in this research involves evaluating the role that media-based efforts play in setting an agenda or framing an issue. The #blacklivesmatter movement is a case in point. The killing of Brown, along with other episodes in which young black men died at the hands of police, led people to use that hashtag on Twitter in order to frame these tragedies as part of a larger narrative about police treatment of people of color. But violent protests against those deaths led to a reframing of the entire story as one that ended in “rioting.” Both events on the ground and people’s interpretation of those events, in other words, can help set the agenda for an issue.

Impact | Just because journalists have exposed people to information doesn’t mean that people will take action or demand policy changes in response to that information. Jonathan Stray, a fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, calls this challenge—that of translating media coverage into social impact—“the last mile problem.”8 In certain cases, however, it’s possible to link a specific journalistic project to a discernible policy outcome. Even an article that doesn’t gain wide circulation can cause change if those who do read it are willing and able to act on what they read. (The late Robert L. Bartley, who was editor of the Wall Street Journal opinion page for many years, once said, “It takes 75 editorials to pass a law.”9) Here are some examples of journalism that resulted in real-world social impact.

In 2012, Bloomberg Businessweek published an article that built on research by New Zealand scholars who had documented the forced labor of Indonesian workers on Korean-owned vessels. These vessels were fishing for catch to be exported by New Zealand companies.10 The article caused so much outrage that the New Zealand government quickly enacted legislation that made it a crime, punishable by imprisonment, to exploit migrant workers. The government also passed a law that will require all vessels that fish in New Zealand waters to abide by the country’s labor, health, and safety regulations. After the article came out, moreover, retailers such as Safeway, Wal-Mart, and Whole Foods launched investigations into their supply chains. Some US buyers canceled contracts with New Zealand fish suppliers.11

In 2010, ProPublica published a series of articles that tracked which US doctors had received payments from pharmaceutical companies. Over a two-year period, according to the series, those companies made payments to roughly 17,000 physicians, and these payments totaled more than $2.5 billion. ProPublica provided an app that people could use to find out whether drug companies had given money to their doctors.12 More than 180 outlets picked up the story. “This scrutiny,” according to ProPublica, “has prompted tightening of disclosure rules.”13 The University of Colorado, Denver overhauled the conflict-of-interest policies that apply to its teaching hospitals, for example, and Stanford University took disciplinary action against five of its faculty members.

In 2014, the Center for Public Integrity published a series on how Luxembourg had enabled major companies such as Coach, Disney, FedEx, Ikea, Koch Industries, and Pepsi to evade taxes by registering in that country so that they could take advantage of loopholes in various treaties.14 The story splashed across front pages throughout Europe. Within days, there were calls for Jean-Claude Juncker—a former prime minister of Luxembourg, who had just been chosen to head the European Commission—to resign from his new post. The European Union, meanwhile, moved to pass a law that would ban these kinds of sweetheart deals.15

Some investigative reporting teams have developed systems to track the real-world impact of their work. They use these systems to monitor editorials that cite their investigations or policy changes that come in the wake of their reporting. Each year, ProPublica publishes updates on the status of issues that it has covered in its major reporting projects. And Participant Media, an entertainment company that produces films with social and political themes, has launched the Participant Index, an attempt to capture outcomes that go beyond policy change. The company conducts surveys to determine whether people who have seen specific Participant films have then taken related actions—signing a petition, making a donation, or joining an organization, for example. Participant has invited newsrooms and advocacy organizations to use its method as well.16

The Impact of Measurement

Nonprofit newsrooms and the organizations that fund them will continue to hone their use of new and existing metrics. Tools that can measure not just “reach” but also “influence” and “impact” are in their infancy. Yet they are becoming ever more sophisticated, and our ability to apply them has advanced dramatically.

Today, we know a lot more than we did previously about news consumption habits and about the way that ideas spread, and this knowledge can help us understand how social change occurs. Research shows that change usually takes place over the span of decades and that media coverage has an impact only when other social forces are also at work. Take the case of female foot-binding in China. For hundreds of years, the philosopher Anthony Appiah notes, Chinese writers had called attention to the dangers of that practice. But only when young members of the country’s elite became ashamed of foot-binding did Chinese authorities begin to issue decrees against it.17

Some kinds of impact are easy to measure—the passage of a law, the ousting of a corrupt politician. Other forms of social change (like the demise of foot-binding in China) involve a transformation of cultural norms. Almost inevitably, that kind of change is a long and complex process. Even episodes of seemingly rapid change, such as the shift in Americans’ attitudes toward gay and lesbian marriage rights, typically follow an extended period of political activism and cultural ferment.

In that context, consider again the ProPublica report titled “Deadly Force, in Black and White.” It’s probably unrealistic to expect that such a report would lead to an indictment of the police officer who shot and killed Michael Brown. But that measure of impact is not the only one that matters. By bringing attention to the disproportionate use of force against black men, the ProPublica investigation may help shift public attitudes about that subject, and it may open a dialogue both about police practice and about the persistence of racial bias in the United States.

As media organizations become ever more dependent on funding that doesn’t come from advertising or subscriptions—funding that comes with pressure to demonstrate real-world impact—they and their supporters should heed the risks that this trend involves. Funders, for their part, must avoid the trap of supporting only groups that are able to deploy the latest technology. A small journalism NGO in Africa, for example, is unlikely to have the staff, skills, or resources to use sophisticated impact measurement tools. Would we want a world in which that kind of group cannot get funding? After all, until a journalist actually covers a story, we can’t know whether the story will make a difference.

Media organizations, meanwhile, must watch out for threats to newsroom independence. The increasing focus on measurable impact may become an excuse to decide that only some kinds of coverage are worth supporting. If newsrooms limit their reporting to stories that can have immediate effects or quantifiable results, they might be unwilling to cover large, persistent—yet vitally important—social problems. Ultimately, the impact that journalists can have on society will erode if they must serve the whims of funders. That is true whether the funders in question are government officials, advertisers, corporate owners, or well-intentioned philanthropists.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Ethan Zuckerman & Anya Schiffrin.