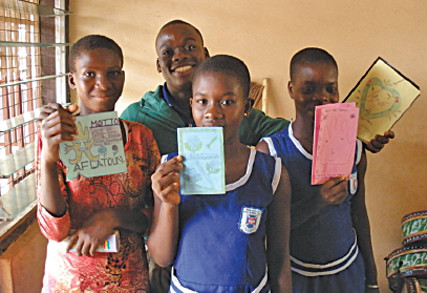

Junior high school students

display their Aflatoun

Savings Workbooks

at the Pantang School in

Ghana’s Abokobi district. (Photo courtesy of Jessica Benjamin, Financial Education Fund)

Junior high school students

display their Aflatoun

Savings Workbooks

at the Pantang School in

Ghana’s Abokobi district. (Photo courtesy of Jessica Benjamin, Financial Education Fund)

Even before the 2007-08 financial crisis, Americans weren’t in great long-term financial shape. We’ve overborrowed, with average credit card debt more than $5,000; and 50 percent of Americans haven’t adequately saved for retirement. One plausible approach to this problem has been to teach financial literacy, explaining basic principles of saving, planning, and spending responsibly. Unfortunately, research doesn’t generally show that savings seminars positively affect people’s long-term financial outcomes. The journey from knowing what we should do to actually doing it can be difficult.

That’s why we wanted to know what would happen if we started teaching good behaviors early. We asked: Are kids easier to influence? Could even a small and early influence on kids have big cumulative societal benefits over the course of their lives? To make it more interesting, we decided to look at a country with a very low savings rate: Ghana.

Aflatoun, an NGO based in the Netherlands, has developed a financial education curriculum for schools that uses local partners in 83 countries to train teachers. At the heart of the program is a simple group “bank” in the form of a locked money box and a passbook kept by the teacher, where kids in an afterschool program can save money and record deposits and withdrawals. Savings lessons are embedded in a broader social and emotional development curriculum, linking saving to individual rights and responsibilities, along with social and financial enterprise education.

The key to a rigorous study about whether a social program works is to compare how people’s lives changed with how they would have changed had the program not existed. When feasible, the best way to do this is with a randomly assigned comparison group. In this case, we evaluated two program groups: one who got the full Aflatoun curriculum, and one who got just the basic financial training. This latter group—who received the money box and skills training, but not the broader psychosocial development curriculum—we called the “Honest Money Box” group (HMB); having it allowed us also to compare the effects of a simpler intervention. Fifth and 7th graders in 135 schools participated, with schools randomly assigned to one of the two savings programs or the comparison group.

After a full school year, our surveyors asked both groups about a host of savings attitudes and behaviors. The surveyors also looked for differences among students who’d gone through the programs in risk tolerance, self-confidence, and interpersonal relations.

To tap the wisdom of the crowd, we posted a description of the study on SSIR’s website and asked readers to predict what we found. Readers could vote for positive effects of the full Aflatoun program, the HMB, both, or neither.

It turns out that both programs had a modest but measurable impact on savings. About 51 percent of kids in the comparison group reported savings, and participating in either Aflatoun or HMB boosted the savings rate by an additional 4 percent.

Most of the online voters predicted correctly, with 56 percent guessing both would have an impact. Twenty-seven percent said Aflatoun only, 12 percent said HMB only, and a pessimistic 5 percent said neither would have an impact.

Moving savings into a social context might also spur other social activities. At the Nkwanta South district school in a poor rural district of the Volta Region, students had never been involved in a club activity. But once they had a savings group, they started a stationery store, selling pencils, books, water bottles, and similar items. An Aflatoun group in the Pantang Basic School near Accra started selling pastries and a children’s newspaper at PTA meetings, and embarked on such pro-social activities as organizing their own savings outreach programs and visiting foster home children.

One of the few differences we found in financial outcomes between the Aflatoun and HMB programs was that kids in the HMB program were more likely to work outside of school. As one HMB student told us: “I work hard every Saturday and Sunday at the market. … I used to spend all my money on video games and other entertainment items, but since I joined the Honest Money Box club I have changed the way I spend.” Whether this is positive is still in question, because working could compete with school. A possible side effect of encouraging savings without broader psychosocial development could be an increase in child labor.

We did, however, see reductions in the attraction to risky bets, with students in both intervention groups showing higher levels of risk aversion. But by and large, we saw no differences from the comparison group across the range of other psychosocial factors we measured. So even in difficult conditions an intervention can increase savings, and a relatively straightforward program can have roughly the same outcome as a more rigorous one.

As in all single studies, there are caveats—we measured outcomes at only one point in time. Whether the effects persist is unknown, and we relied on kids’ self-reports. Yet having a well-balanced study with equivalent groups, who received either no training or basic training, also lets us see what really works for the future.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Annie Duflo & Dean Karlan.