SPONSORED SUPPLEMENT TO SSIR PRODUCED FOR THE COLLECTIVE IMPACT FORUM

Collective Insights on Collective Impact

This special supplement features the most recent thinking and learning about how to use the collective impact approach to address large-scale social and environmental problems.

-

Essential Mindset Shifts for Collective Impact

-

Defining Quality Collective Impact

-

The Role of Grantmakers in Collective Impact

-

Power Dynamics in Collective Impact

-

Roundtable on Community Engagement and Collective Impact

-

Aligning Collective Impact Initiatives

-

Learning in Action: Evaluating Collective Impact

-

Achieving Collective Impact for Opportunity Youth

-

Making Public Policy Collective Impact Friendly

Collective impact is at a strategic inflection point. After almost three years of extraordinary hype, investors are wondering what this concept really means when they receive proposals that simply replace the term “collaboration” with “collective impact.”1 Researchers are perplexed by so-called new ways of doing business that look eerily similar to what they have already studied. And most important, leaders and practitioners in communities are confused about what it really means to put collective impact into action.

As the founding managing director (Jeff Edmondson) and a national funder (Ben Hecht) of StriveTogether, we remain bullish on the concept of collective impact. For us, it is the only path forward to address complex social problems—there is no Plan B. Yet to realize its promise, we need to define in concrete terms what “quality collective impact” really means. For that reason, we have spent the last 18 months aggressively working on a coherent definition to increase the rigor of these efforts, so that this concept does not become watered down. We feel confident that if we agree on core characteristics, we can stop the unfortunate trend of “spray and pray”—haphazardly launching programs and initiatives and hoping that good things will happen. Instead, we can crystallize the meaning of collective impact and solve seemingly intractable problems.

First, some background on the organization. StriveTogether is an outgrowth of The StrivePartnership in Cincinnati, Ohio, which is based at KnowledgeWorks and was featured in the first article on collective impact, published in the Winter 2011 issue of Stanford Social Innovation Review. StriveTogether has pulled together more than 45 of the most committed communities around the country to form the StriveTogether Cradle to Career Network. Its aim is not to start new programs—we have plenty. Instead, the network is focused on articulating how cross-sector partners can best work together to identify and build on what already works—and innovate as necessary—to support the unique needs of every child.

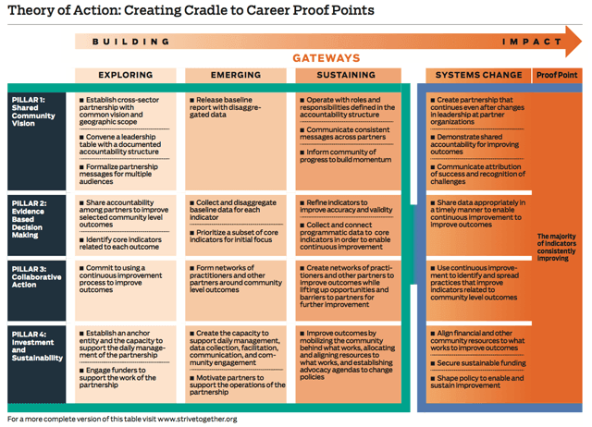

Fortunately, the members of the network have been willing to “fail forward” by sharing not only their successes, but also their struggles, using the lessons they have learned to advance the field. Their experiences during the last three years have contributed to the creation of a vital tool called the StriveTogether Theory of Action (TOA), which provides a guide for communities to build a new civic infrastructure.2 The TOA highlights a community’s natural evolution and provides the quality benchmarks that, taken together, differentiate this work from traditional collaboration. It uses what we call “gateways,” or developmental stages, to chart the path from early on (“exploring”), through intermediate and later stages (“emerging” and “sustaining”), and finally to “systems change,” where communities see improvement in educational outcomes. We define systems change as a community-wide transformation in which various partners a) proactively use data to improve their decision-making and b) constantly weigh the impact of their decisions on both their own institutions and the broader ecosystem that works to improve the lives of children. The ultimate result—which we are witnessing beyond Cincinnati in partnerships like The Roadmap Project in Seattle—are examples of communities where we see sustained improvement in a limited set of measurable outcomes that are critical for kids to succeed and for communities to thrive.

The TOA is not perfect: for example, we realize this work is not linear. Nonetheless, the framework captures the fundamental building blocks necessary for collective impact. As more communities adopt it, it will help us identify the most important aspects of our work.

Four Principles

Four principles underlie our work across the Theory of Action and lead to long-term sustainability.

Build a culture of continuous improvement | Data can be intimidating in any field, but this is especially true in education, where numbers are most often used as a hammer instead of a flashlight.3 To counter this pitfall, community leaders from Albany, N.Y., to Anchorage, Alaska, are creating a culture that embraces data to generate ongoing improvement.4 At the heart of this process lie the “Three I’s”: identify, interpret, and improve. Community leaders work with experts to identify programmatic or service data to collect at the right time from a variety of partners, not simply with individual organizations. They then interpret the data and generate user-friendly reports. Last, they improve their efforts on the ground by training practitioners to adapt their work using the new information. Dallas’s Commit! partnership provides a good example. There, leaders identified schools that had achieved notable improvement in third grade literacy despite long odds. The backbone staff worked with practitioners to identify the most promising schools and interpret data to identify the practices that led to improvements. District leaders are now working to spread those practices across the region, using data as a tool for continuous improvement.

Eliminate disparities | Communities nationwide recognize that aggregated data can mask real disparities. Disaggregating data to understand what services best meet the needs of all students enables communities to make informed decisions. For the All Hands Raised partnership in Portland, Ore., closing the opportunity gap is priority number one. It disaggregates data to make disparities visible to all and partners with leaders of color to lead the critical conversations that are necessary to address historic inequities. The partnership engaged district leaders to change policies and spread effective practices. Over the last three years, the graduation gap for students of color has closed from 14.3 percent to 9.5 percent. In several large high schools the gap is gone.

Leverage existing assets | The all-too-common affliction “project-itis” exerts a strong pull on the social sector, creating a powerful temptation to import a new program instead of understanding and improving the current system. At every level of collective impact work, practitioners have to devote time, talent, and treasure toward the most effective strategies. Making use of existing assets, but applying a new focus to them, is essential to demonstrating that collective impact work truly represents a new way of doing business, not just an excuse to add new overhead or create new programs. In Milwaukee, Wis., and Toledo, Ohio, for example, private businesses lend staff members with relevant expertise to help with data analytics so that communities can identify existing practices having an impact.

Engage local expertise and community voice | Effective data analysis provides a powerful tool for decision-making, but it represents only one vantage point. Local expertise and community voice add a layer of context that allows practitioners to better understand the data. Success comes when we engage partners who represent a broad cross-section of the community not only to shape the overall vision, but also to help practitioners use data to change the ways they serve children. In San Diego, the City Heights Partnership for Children actively engages parents in supporting their peers. Parents have helped design an early literacy toolkit based on local research and used it to help other families prepare children for kindergarten. As more families become involved, they are actively advocating early literacy as a priority for local schools.

The Promise of Quality Collective Impact

For a more complete version of this table visit www.strivetogether.org.

For a more complete version of this table visit www.strivetogether.org.

Collective impact efforts can represent a significant leap in the journey to address pervasive social challenges. But to ensure that this concept leads to real improvements in the lives of those we serve, we must bring rigor to the practice by drawing on lessons from a diverse array of communities and defining in concrete terms what makes this work different. The StriveTogether Theory of Action represents a step in that direction, building on the momentum this concept has generated during the past three years.

As US Deputy Secretary of Education Jim Shelton has simply put it: “To sustain this movement around collective impact, we need ‘proof points.’” These come from raising the bar on what we mean by “quality” collective impact and challenging ourselves to meet higher standards. In so doing, not only will we prove the power of this concept, but we can change the lives of children and families in ways we could never have imagined.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Jeff Edmondson & Ben Hecht.