Mercy Corps leadership training participants from (left to right) Taiwan, Haiti, Indonesia, and Taiwan. (Photo courtesy of Mercy Corps)

Mercy Corps leadership training participants from (left to right) Taiwan, Haiti, Indonesia, and Taiwan. (Photo courtesy of Mercy Corps)

Neal Keny-Guyer, chief executive of Mercy Corps, says he likes to think he would have recognized the potential of graduates coming out of Indian and African universities in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But he acknowledges that such national talent was long overlooked in the international aid and development world. In the late 1970s, when he was studying management at Yale University to prepare for a career in global relief and development, Keny-Guyer says, senior staff at international agencies came exclusively from the West. This was not surprising, because many aid organizations were founded by Westerners. Mercy Corps, for example, was founded in 1979 by American Dan O’Neill, who was spurred into action by massacres in Cambodia.

Keny-Guyer’s background is typical of international non-governmental organizations’ senior staff. An American from a middle-class family who found himself moved by problems he saw at home and abroad, he worked with inner-city youth in Washington, D.C., and Atlanta after earning a BA in public policy and religion from Duke University. In 1980, he went to Thailand to help Cambodian refugees, working for CARE and UNICEF. When he finished his MA in public and private management at Yale in 1982, he began working for Save the Children.

Fast forward to 2006. Keny-Guyer, who has worked for Mercy Corps since 1994, was in Sudan’s Darfur region, meeting with international staff—those in senior leadership or technical positions. Of the two dozen people he met, only two were from the West. The rest were multilingual, highly educated professionals from Africa and the Middle East. Keny-Guyer remembers thinking as he surveyed the room: “God, I’m kind of glad I’m not trying to get a job today.” Less than half of the organization’s international staff today is from the United States or Europe; 95 percent of the 4,500 people who work for Mercy Corps are from the countries where the organization is operating. At one time, Keny-Guyer says, worrying about recruiting and training was seen as getting “in the way of delivering the service” at big international NGOs. It’s difficult, he says, to specify when attitudes began to shift. “I think it was an evolution that reflected changes in the world.”

Increasingly, hiring talent with deep knowledge of local problems and challenges is also seen as a way to build effectiveness, impact, and sustainability.

For an international organization, having a truly international workforce can be seen as a matter of fairness and equity. And those are important perceptions and commitments for agencies fighting poverty, disaster, disease, and injustice. But increasingly, hiring talent with deep knowledge of local problems and challenges is also seen as a way to build effectiveness, impact, and sustainability into the job of doing good. And that is crucial for organizations facing new and complex crises, often with shrinking budgets and questions about whether old aid and development methods have worked quickly enough, or at all.

The obstacles to finding the right international staff can’t be played down; they include shaking off entrenched assumptions and institutional cultures and competing for talent with deep-pocketed multinational corporations. But organizations are stepping up, from startups bringing entrepreneurial fervor to development work, to larger, more traditional international agencies.

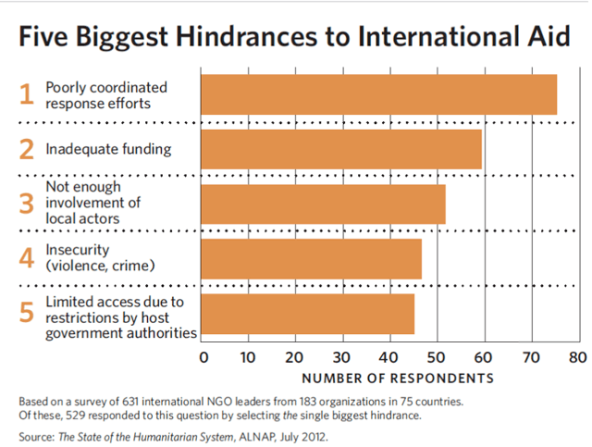

Paul Knox Clarke, who heads research and communications for the Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action (ALNAP), says that how international organizations are led, and who leads them, have become increasing concerns in recent years—for everyone from donors to on-the-ground aid workers. ALNAP was created in 1997 following a multi-agency evaluation of the Rwanda genocide. It brings together NGO officials, academics, and others committed to improving humanitarian response. A 2012 ALNAP study, based in part on interviews with more than 60 NGO leaders and those who closely observed them, found, “It is still unusual for nationally recruited staff to move into international leadership roles and for their leadership skills to be recognized.… There is a sense that more needs to be done, for example, through mentoring and challenging assumptions—albeit not openly expressed—about the experience and skills of nationally recruited staffs.” (See “Five Biggest Hindrances to International Aid,” below.)

Numbers, Clarke says, are hard to pin down. But he adds that few would argue that the leaders of most international NGOs are representative of the global population. Yet such organizations were established to work in different cultures, often in situations that demand collaboration with governments and other agencies. “It’s crossing cultures. So it’s important to have people who understand the cultures,” he says. A model familiar to many who have worked in aid and development is the charismatic Westerner, often a man, arriving in a developing world crisis to impose order. What Clarke calls a “heroic assumption” about what makes a good leader can be self-perpetuating. “If you have the white man’s idea of leadership, it’s not surprising that you keep getting white, male leaders,” he says. Other cultures might bring more collaborative ideas. Pursuing diversity, Clarke says, “might usefully challenge some of the assumptions about what leadership actually is.”

LEADERS BREAKING THROUGH

Nigerian-born Michael O’Brien-Onyeka is among the few who have broken through to the ranks of international NGO leadership. In early 2012, he became executive director of Greenpeace’s Africa operations, based in Johannesburg, South Africa. O’Brien-Onyeka also has held high-level posts for Amnesty International, the National Democratic Institute, and Oxfam in Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. The 43-year-old grew up in the aftermath of Nigeria’s civil war in the late 1960s, which he says honed his social conscience. As a sociology and law student at the University of Lagos in the 1990s, he campaigned against military rule, becoming Amnesty International’s spokesman in Nigeria.

O’Brien-Onyeka says history explains why most senior posts at most international organizations are held by Westerners. The organizations were formed in the West and built experience and expertise there. ALNAP has identified some 4,400 NGOs working in the humanitarian sector worldwide, which is dominated by the United Nations, the International Red Cross, and five giant international NGOs: Médecins Sans Frontières, Catholic Relief Services, Oxfam, Save the Children, and World Vision, all based in Europe or the United States, with an average of nearly six decades of experience and expertise. Overall, 45 percent of the international NGOs are based in the United States, according to ALNAP.

But O’Brien-Onyeka says Western domination cannot be the future, if such organizations want to continue to make a difference. Greenpeace, for example, has been in and out of Africa, waging campaigns against Western oil companies operating in Nigeria and accused of environmental degradation. “People jet in, work with local organizations, put up the Greenpeace flag, stay for two weeks, then leave. It’s not sustainable,” says O’Brien-Onyeka. “To do longterm work, you can’t shy away from investing in people. It makes socioeconomic sense to invest locally in people.” Greenpeace opened its Africa office in 2008, implementing a new vision to “Africanize the Africa staff of Greenpeace,” says O’Brien-Onyeka. A year later, Kumi Naidoo, a South African who had been an antiapartheid activist in his homeland, was named international executive director of Greenpeace, the first African to head the 42-year-old organization. Today, “we face a global challenge,” says O’Brien- Onyeka, referencing climate change and environmental protection. “It’s good to get input from leaders from the South.”

Monique Gbha-Sato, from Centre d’Ecoute, a Mercy Corps partner in the Central African Republic. (Photo by Sean Sheridan for Mercy Corps)

Monique Gbha-Sato, from Centre d’Ecoute, a Mercy Corps partner in the Central African Republic. (Photo by Sean Sheridan for Mercy Corps)

O’Brien-Onyeka believes that Greenpeace shares “basic principles of equity, fairness, equal opportunity” with other organizations where he has worked. But in much of the developing world, Greenpeace has to uproot the perception that it is “middle-class, Caucasian, slightly hippy-ish”—both out of touch with the concerns of poor people and clumsy at influencing public opinion or government action. A sense that international agencies are pushing Western agendas can lead to resentment that is only exacerbated if those same agencies are seen as denying locals advancement. “I consider myself a passionate pan-Africanist. But I don’t want to follow the bunker mentality route,” O’Brien-Onyeka says. “If our politicians got their acts together, maybe we wouldn’t have international NGOs running around.”

NGOs should be pushed to transfer skills to local workers, O’Brien-Onyeka avers. He says Greenpeace is committed to such internal development, focusing on developing skills among local staff. This capacity-building works both ways, as local leaders can bring insights and depth to international organizations. O’Brien-Onyeka says Africans on the ground have questioned whether Greenpeace’s trademark protests—activists scaling oil platforms, chaining themselves to power plants, sailing Rainbow Warrior ships into the path of illegal fishing vessels—can sway publics and governments on the continent. “In Africa, our mandate is to be a solution-oriented organization,” O’Brien-Onyeka says. “We have to present a feasible alternative, not just talk about it.”

The good news for organizations cultivating leaders from developing countries is that the pool of candidates to be hired and nurtured is growing. According to a 2010 UNESCO report, fewer than 200,000 students were attending universities and other tertiary educational institutions in sub-Saharan Africa in 1970. That number grew at an average of 8.6 percent a year—compared to an international rate of 4.6 percent—to reach more than 4.5 million in 2008. Asia, too, is making gains. According to UNESCO, 6 percent of India’s post–high-school-age population was in a tertiary institution in 1991. By 2010, that number had increased to 18 percent. In China, between 1991 and 2010, the percentage of college-age youths attending college went from 3 percent to 26 percent.

The NGO field is growing, too. ALNAP, the humanitarian response group, estimates that the international humanitarian sector alone employed 141,000 people in 2010 and that the annual growth rate for personnel has been at least 4 percent in recent years. ALNAP also has found growth in national and local NGOs, but exact numbers are hard to pin down.

The good news for organizations cultivating leaders from developing countries is that the pool of candidates to be hired and nurtured is growing.

Kiran Martin’s NGO, Asha, is among that number—and she is part of the national leadership phenomenon. While enrolled in the University of Delhi’s Maulana Azad Medical College, she decided that she wanted to do something to help her hometown’s poor. In 1988, as a newly qualified pediatrician, she began visiting a nearby slum where there was a cholera outbreak. She went on to organize a network of activists working to improve health, education, and other services in the slums. Asha (Hindi for “hope”) now serves 50,000 slum dwellers in 50 Delhi slum colonies. It also works with several international organizations, partnering their global experience and fundraising capability with Martin’s local knowledge.

“If you really want to see people’s lives transformed, then it’s a long-term commitment,” Martin says. “Otherwise, you’ll be providing a service; you’re not going to eradicate poverty. To eradicate poverty, you have to deal with so many stakeholders. And that’s very difficult for a foreigner to do. Flying in and out, I don’t think is the answer.” Martin adds that it was only after Asha was well established in the late 1990s that international NGOs began trying to recruit her.

AN UPSTART THAT LOOKS LOCAL

Click on Village Enterprise’s website, and East Africans are country directors, assistant country directors, regional managers, and operations managers in Kenya and Uganda. You might think it is a local NGO, like Asha. But Village Enterprise is based in San Carlos, California. Its website displays its commitment to training local leaders. “It’s even more local than it looks,’’ says Dianne Calvi, CEO of Village Enterprise, which invests in café owners, tailors, carpenters, kale and tomato farmers, and other tiny businesses in extremely poor communities in East Africa. Village Enterprise also finds local leaders to mentor micro-entrepreneurs. “All of our mentors are local. They’re actually from the communities in which they work,” Calvi says.

Brian Lehnen and Joan Hestenes started Village Enterprise in 1987, operating it as an all-volunteer organization from their San Diego home. In 1995, Lehnen abandoned a biotechnology career to run Village Enterprise full time. By the time he retired in 2010, handing over the nonprofit to Calvi, Village Enterprise had helped create more than 20,000 small businesses. “There has always been at Village Enterprise a real appreciation for the importance of local participation for building support within communities,” says Calvi. “The value of indigenous leadership” is part of the organization’s culture.

Calvi, who studied at Stanford University and at Italy’s Bocconi University, has worked in multinational management consulting and directing nonprofits. Before coming to Village Enterprise, she was president of Bring Me A Book, a literacy-building foundation that serves poor families in California and has grown to operate in Hong Kong, Malawi, and Mexico. While working with Bring Me A Book, which trains local community members as reading trainers, Calvi says she learned the importance of having leaders who spoke local languages and understood their communities intimately. She adds that she would not have been as tempted by the Village Enterprise position if its field staff were Stanford PhD students.

Village Enterprise mentors were once volunteers who were paid small stipends. The organization decided a few years ago to make the mentors full-time employees and increase their training. Some training is provided by Village Enterprise Fellows, who often are Westerners whose stints are short-term. “There can be good reasons for bringing non-local people to augment what the locals have,’” Calvi says. “The goal of our fellows is to transfer know-how.” Village Enterprise brought in an outsider, Barcelona-born Konstantin Zvereff, as its senior director of programs and operations, overseeing operations in Kenya and Uganda. Zvereff, an expert in finance, had the international experience Village Enterprise sought. “Finding Africans who have the skill set you’re looking for and the experience you’re looking for can be a challenge,” Calvi says. “Hiring at that level can be a challenge.”

The organization’s Uganda country director, Charles Erongot, is one of their star examples of leadership development. He started as a volunteer mentor 14 years ago, recently served as the main speaker at Village Enterprise fundraisers in the United States, and attended an international conference in Mexico to meet World Bank and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation officials. This foreign trip, his first, was a step toward developing the skills that might one day make Erongot a contender for Zvereff’s job.

Calvi says her organization has had little interest from non-Africans for its country director positions. Other agencies place their country directors in relatively cosmopolitan Nairobi or Kampala, whereas Village Enterprise country directors live in provincial centers, in houses on dirt roads, with daily power outages and no international schools nearby—reasons Westerners may not apply. “We really have a very lean, program-oriented field orientation,” Calvi says. “There really isn’t a need to have someone in the capitals.”

Calvi says staff conference calls can take longer, as participants navigate a Babel of accents, and the workplace can be a complex place when Western and local ways clash. “It is more challenging developing local leaders, because it’s always easier for people to work with people who are like them,” Calvi says. But “you really need local people to have significant impact.” Calvi describes a Ugandan mentor whose depth of local knowledge Village Enterprise has drawn on. Vicky Achan works in an area in Uganda devastated by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), whose leader Joseph Kony is wanted by the International Criminal Court on charges of war crimes. Achan’s entire family was killed by the LRA, a tragedy that gives her empathy and authority when she urges peace and cooperation. “Even more so in a crisis, it’s important that you have local people,” Calvi says.

A NOBEL LAUREATE ADJUSTS

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), founded in Paris in 1971, is perhaps the quintessential large crisis-driven international relief and aid agency. Winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize, MSF responds to crises—a cholera outbreak in Zimbabwe, a flood of refugees in Chad—with a well-practiced strategy. “You need to go very quick, with sometimes very large staff contingents,” says Gilles Van Cutsem, MSF’s medical coordinator in Cape Town, South Africa. “You will have much more external staff in a classic emergency than in a long-term project.”

MSF has had to develop a new strategy to confront the longterm crisis of AIDS in South Africa, however, which is home to the highest number of people in the world infected with HIV. The South African experience has had a profound influence on MSF’s culture. More than 5 million South Africans, out of a population of 50 million, are living with HIV. MSF knew it could not bring in enough experts to cope. So it initiated projects aimed at making the best use of South Africa’s scarce human resources. Nurses were trained to take on some of the tasks that once only doctors could do. Then health workers were trained to take on some nursing tasks, at times working outside clinics, to reduce clinic waiting times and free up doctors and nurses to start new patients on treatment and see patients with complications.

In the early years, South Africa’s president and its health minister denied that antiretroviral (ARV) drugs could be an effective treatment for AIDS. That position has changed, with a new health minister setting ambitious goals for getting more South Africans on ARVs. To cope with the resulting increased caseload, MSF has experimented with patient clubs, in which those who will be on ARVs for the rest of their lives meet bimonthly with a lay counselor to collect their drugs, undergo a general health assessment, and talk about any problems they are experiencing. Nurses attend some meetings.

The majority of MSF staff in South Africa is South African, Van Cutsem says. He notes that MSF has an advantage in recruiting: “In general, MSF attracts incredibly motivated people by its reputation. We don’t pay very well, but we have a reputation of making things work.” One of his best hires, Nompumelelo Mantagana, was a nurse who lost close relatives to AIDS. Mantagana made it her mission to help people living with HIV, even when she found herself in opposition to the government’s policy of denial while working at a government clinic. She left her government job for MSF, then returned to the government as a senior manager when public policy shifted to embrace ARV treatment. Her experience and expertise was transferred, not lost, and South Africa was a step closer to being able to do without MSF. “It’s really the ideal situation,” Van Cutsem says.

Partly as a result of the deep commitment necessitated by its AIDS work, MSF established an office in South Africa, the first in Africa, in 2006. The office has given African voices greater weight within the organization, Van Cutsem says. He cited as an example South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), an independent AIDS activist group with whom his office has worked closely. When TAC set up a hotline for monitoring drug shortages at government clinics, it won praise from government officials, who said they were getting crucial information from TAC faster than from their own bureaucrats. When MSF saw the project’s effectiveness, it began working with groups in neighboring Mozambique to replicate it. “We’re still learning, every day, from this interaction with civil society,” Van Cutsem says. “It is seeing things from a different perspective. MSF is becoming more international than it ever was before, and that’s a very interesting development within MSF.”

THE SOCIAL ENTERPRISE VIEW

Mike Lin’s mission is to ensure the continued growth of cell phone use in Africa and Asia, where phones link doctors with patients and farmers and fishermen with markets. Lin takes a businesslike approach to development, which may be part of the reason he was quick to see the benefits of hiring and nurturing local talent. His San Francisco-based company, Fenix International Inc., markets ReadySets—cell phone charging devices powered by sun, wind, bicycle, or, in a pinch, conventional sources of electricity. The devices sell for $150 to small businesspeople. Villagers beyond the grid in countries like Uganda and Rwanda buy time on the ReadySets to charge their cell phones, allowing ReadySet purchasers to recoup the cost of their investment in a few months. “We see ourselves as a mission-driven, for-profit social enterprise,” Lin says. Fenix could easily have been a nonprofit. Instead, starting in 2009, it partnered with African cell phone companies, which are happy to help distribute and sell ReadySets because more power in remote villages means villagers spending more time and money on their cell phones.

Fenix founder Mike Lin (above left) helps an MTN Rwanda employee use a solar-powered cell phone charger. (Photo courtesy of Fenix)

Fenix founder Mike Lin (above left) helps an MTN Rwanda employee use a solar-powered cell phone charger. (Photo courtesy of Fenix)

Lin says that if everyone working at his Fenix social enterprise was Stanford-educated, like himself, his company would lack the ideas it needs to thrive. “That closed community, that monoculture, is ultimately a weakness,” he says. Lin has benefitted from an up-close look at the culture of emerging African multinationals. The cell phone companies with which he works draw staff from across Africa, some of whom Lin has unabashedly poached. “It’s a great way for us to grow.” He’s also found talent at the University of Nairobi and Uganda’s Makerere University. Fenix managers in Africa include an American leading East African operations, a British marketing director, and a Rwandan and a Ugandan heading the team in Rwanda. Several Ugandans are sales managers.

Some sales staff lack formal education but are driven and gregarious. They know their markets. With in-house training, they can be ready for other opportunities. “Qualified people are everywhere,” Lin says. “It’s about finding their strengths and addressing their weaknesses. We don’t care if they’ve never left their village.” And if he does decide a promising employee needs international experience? “That, again, is something you can develop. You buy them a plane ticket.”

Ned Tozun shares Lin’s enthusiasm about the depth and breadth of the talent pool. Tozun’s social enterprise, d.light, sells solar lanterns, a business inspired in part when Sam Goldman, d.light’s co-founder, was serving in the Peace Corps in Benin and saw a neighbor’s son badly burned in an accident with a kerosene lamp. Tozun and Goldman, who met at Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, have regional offices in Kenya, India, China, and the United States. They sell products in more than 40 countries. They have been able to hire locals away from multinationals—people, Tozun says, “who do want to change the world, and have corporate experience.” Tozun says he can’t ask staff to take salaries radically less than what they were earning from the likes of Unilever. But “people are ready to take some cut in order to do something they think is really valuable or fulfilling.” Many of his team members were educated outside the United States, giving Tozun a sense of the rigor of programs at universities in India and Africa. But he does not recruit directly out of university, preferring staff who already have corporate experience. That could change, Tozun adds, as d.light grows and develops in-house training capacity.

Tozun has searched a year to make some hires. Waiting to find the right person is less costly than taking on the wrong person, even though he has investors to please and deadlines to meet. D.light’s field managers are from India, Kenya, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria. Tozun’s vice president for operations came to d.light with more than 30 years of experience in China, his homeland and a vast and challenging market. “To have that sort of background in your tool set—it’s unbelievable,” Tozun says. And it’s not by accident. Months after founding their company, Tozun went to China and Goldman went to India to set up operations and recruit.

EMPLOYING AHEAD

A decade ago, Mercy Corps began internal discussions about what the organization could learn from the corporate world to develop staff. Mercy Corps started its in-country training program in 2009 with one aim: to equip locals to move into senior positions. A “mini-MBA” program emerged, says Neal Keny-Guyer, much of it web-based, with help from Portland State University’s business school.

Mercy Corps now seeks out staff at local universities, NGOs, and government. But Keny-Guyer does not limit the search to what he calls “traditional channels of leadership,” as they might yield candidates who are only part of the elite, or leave out women. Grassroots organizations that Mercy Corps works with can be a source of talent. “You want pathways for alternative leaders to emerge,” Keny-Guyer says. “That’s critical, but hard to do.” Because nations like China, India, Brazil, Turkey, and South Korea are developing their own aid and relief agencies, Keny-Guyer portrays the search for local talent as also a matter of enlightened self-interest.

Arsene Babako, Mercy Corps Protection Facilitator in Bangassou, Central African Republic. (Photo by Sean Sheridan for Mercy Corps)

Arsene Babako, Mercy Corps Protection Facilitator in Bangassou, Central African Republic. (Photo by Sean Sheridan for Mercy Corps)

Researchers at ALNAP have similarly noted these developments, citing increasing strength among “Southern International NGOs” in Asia. In its 2012 “State of the Humanitarian System,” an ambitious review that incorporates surveys of hundreds of national and international NGO personnel, ALNAP reported, “A growing number of aid-recipient states, particularly in Asia and Latin America, are establishing and strengthening national systems to manage response to natural disasters, and increasingly insist on engaging international aid actors on their own terms.” ALNAP was able to identify some 2,800 national and local NGOs doing humanitarian work in 140 countries, with 41 percent of those in sub-Saharan Africa, 27 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean, 20 percent in Asia, and 4 percent in the Middle East.

Michelle Ndiaye, who is Senegalese and works for a South African think tank, says partnerships among African, Asian, and Latin American development groups are becoming increasingly important. She cites China and India in particular. “The know-how that they have produced could help, because they’ve had similar development trajectories. They’re also learning from us.” Ndiaye has worked across Africa, for the United Nations, for international and national organizations, and in the private sector, in areas ranging from democratization and conflict resolution to the environment. She credits national organizations with finding and developing national talent, but says that they have trouble keeping the leaders they nurture because they offer little opportunity for growth. Now, she says, some NGOs are thinking regionally and even internationally, which will help them gain a greater say in setting the development agendas with international agencies. “It has to be a partnership,” she says.

Frederik Claeye, a specialist in managing NGOs who divides his time between universities in France and South Africa, has watched South African NGOs develop international ambitions. “They bring a different perspective to the table,” he says. “They challenge assumptions we hold about international development.” Keny-Guyer of Mercy Corps agrees that “any international organization has to find a way to partner with these new emerging powers.” Bringing talent, ideas, and perspectives into Mercy Corps in the form of senior staff from the nations where Mercy Corps is working is one way of preparing, he says. “It makes international NGOs more thoughtful, more sensitive, perhaps more effective as well. We’re partnering with a Chinese NGO in Burma. That would have been unthinkable a few years ago.”

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Donna Bryson.