"The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not 'Eureka!' but ‘That's funny ... '" So said Isaac Asimov.

“That’s funny ... ” is exactly what I said upon learning that an unusual foundation received better feedback from its grantees on the helpfulness of its reporting and evaluation process—not once, but twice—than 260 other funders the Center for Effective Philanthropy (CEP) analyzed. Whatever are they doing?

The Inter-American Foundation (IAF) is based in the United States, was set up by US Congress in 1969, and makes grants to support grassroots development across Latin America. On average, its grantees are tiny (with revenue about $225,000), and IAF provides nearly two-thirds of their budget for almost four years.

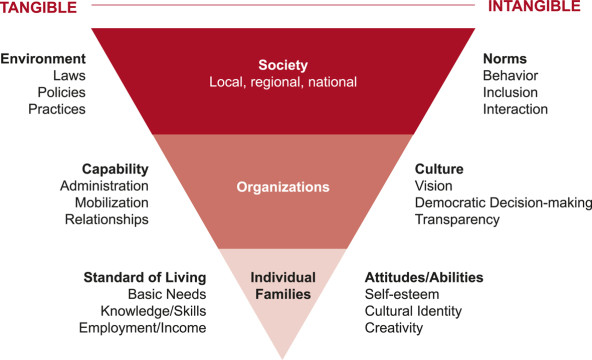

Two features of IAF’s process are conspicuous. First, each grantee can choose the metrics on which to report. IAF’s “metric menu” comprises metrics of tangible and intangible results, as well as effects on individuals, communities, and society. Grantees can request that IAF add new metrics to the menu if none of the existing ones fits. This system is unusual in both its flexibility and in the breadth of work it can accommodate. Second, IAF is highly engaged: IAF visits each grantee several times. This includes biannual visits from an in-country “data verifier,” who supports grantees in the collection, interpretation, and filing of their performance data, and, obviously, checks accuracy.

Couldn’t it just be that …

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

It's not that the grantees just blindly love IAF. Interestingly, of all the funders that CEP has analyzed, IAF scored in the lower half on how fairly grantees feel that the foundation treated them and in the bottom seven percent on its policy influence.

Nor do the results seem like a total fluke: If they were, it would be strange that: 1) IAF has come out on top of this metric twice (though clearly two swallows don’t make a summer), and 2) IAF comes out on top by some margin—in fact, the distance between IAF and other top-scoring foundations for the helpfulness of IAF’s reporting process is larger than the margin for other metrics.

Findings

The first surprise in our findings was that, when asked to list the components of IAF’s reporting and evaluation process, most grantees we interviewed (seven of nine) included the financial reporting and financial audit. These are not normally considered part of reporting or evaluation.

Furthermore, grantees considered the financial audit the most valuable component—more so than the visits, the framework, and so on. Our organization, Giving Evidence, invited each interviewee to allocate an imaginary 100 points between the components of IAF’s reporting and evaluation system, according to the value they ascribe to it: Financial audit came in first, garnering more than a fifth (21 percent) of the total points.

(An interesting side note: We found that grantees barely used intangible metrics such as increase in self-confidence, “belonging,” or internal transparency. They used indicators of tangible outcomes—such as jobs created, credit extended, and skills learned—more than five times as often as intangible outcomes. By far the most preferred indicators are around impact on individuals, as opposed to organizational or societal impact.)

IAF’s Reporting Framework.

IAF’s Reporting Framework.

Overall, the clear finding was that IAF’s reporting and evaluation system is part of its intervention. It helps grantees gain four benefits, each perhaps as useful as the money itself:

- Data: Many of IAF’s grantees previously weren’t gathering data very much or at all, and the process helped them gain an empirical basis for decisions.

- Capacity: Grantees learn to collect, handle, interpret, present, and use data. This is particularly important for organizations that have less-developed management and analysis skills, or that have not previously collected data.

- Confidence: Some grantees gain confidence in their ability to collect data, and in the accuracy and completeness of their data, which is useful in their dealings with other organizations, such as funders and prospective partners.

- Credibility: IAF’s grantees frequently used terms such as “accountability” and “transparency” to describe how data positively influenced their interactions with beneficiaries and communities.

In other words, funders can think of their reporting and evaluation system as a program to build capacity around data. That grantees value such “programs” and funder engagement in reporting fits with findings elsewhere. For example, the S.H. Cowell Foundation and the Richard M. Fairbanks Foundation also scored well when CEP asked their grantees about the helpfulness of their reporting processes, and both those foundations have a highly engaged and consultative reporting process.

Implications for other funders

Many of IAF’s early-stage, “very grassroots” grantees said things like: “Before, we would have gone without collecting these data,” or “We didn’t know how to collect this information [until] the evaluator explained to us.” This suggests that funders supporting young organizations—where part of the idea is to build their skills from a relatively low base—may need to offer significant support before their grantees can produce reliable data. Conversely, funding small or young organizations without helping with data-handling may simply produce data that are wrong. Many grantees said that they used the data they produced for IAF for other projects and their own internal purposes.

We hope that the findings and insights in this case study are helpful to others, and encourage others to share detail about their own ways of operating and their performance results, so that we can build collective understanding of what ways of funding work best in which circumstances.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Caroline Fiennes.