(Photo by Thatcher Cook for PopTech)

(Photo by Thatcher Cook for PopTech)

PopTech, the annual conference in Camden, Maine, has many enthusiasts—groupies even, who claim that when it comes to conferences on innovation, technology, and social entrepreneurship, PopTech is the only annual confab worth going to. The 15-person staff of PopTech adore these endorsements, of course. But they feel they overlook a central fact about PopTech: It is not just a three-day conference; the nonprofit organization is actually a year-round think tank, mentoring organization, scientist and social innovators network, and cultivator of problem-solving labs, projects, and initiatives.

“When we describe ourselves, we have a fill-in-the-blank problem,” says Andrew Zolli, executive director and curator of PopTech. “One of the reasons is because we’re a new kind of organization.”

Zolli, who is a “futures researcher” loquacious and commanding on the intersecting forces of technology, sustainability, and global society, argues that to understand PopTech one must understand its origins not just in the community of technologists like Ethernet inventor Bob Metcalfe and former Apple Computer president John Sculley who bought summer homes in Camden and started the conference in the early 1990s—but in Camden, Maine itself.

“PopTech’s success is rooted in Camden,” argues Zolli. The town boomed economically during the height of the British Empire, thanks to Maine’s textile finishing mills and its well-situated harbor. Camden also boomed culturally because, like many towns along the north Atlantic coast in the 18th and 19th centuries, it fostered a secular meeting hall—in its case, an ornate Victorian opera—where the matters of the day were discussed with vigor.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

PopTech is an extension of that New England vigor, argues Zolli. And, indeed, PopTech inside the Camden Opera Hall can have the feeling of a secular church meeting, though one for highly educated, international, and often visionary citizens. It is also, like the TED, Davos, and Aspen conferences, a grand show for philanthropists, foundation people, and the rich and well connected who seek to do good in the world.

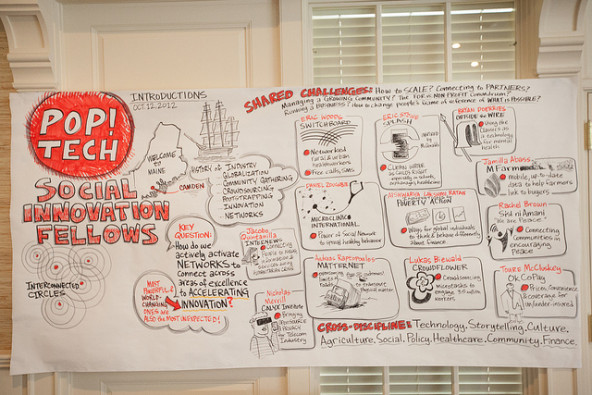

Among the people on display at the conference are PopTech’s fellows, who give five-minute presentations on their organizations or research. They come in two forms: Social Innovation Fellows and Science Fellows, who are generally under 40 and have resumes, as one attendee put it, which “make one feel like a complete loser.”

Take Hayat Sindi, who is the only person to become both a PopTech Social Innovation and Science Fellow. Born to a family of eight children in Makkah, Saudi Arabia, Sindi convinced her father to let her study in England. In her teens, she left for London alone, taught herself English, took her A-levels, and a year later was accepted to King's College. From there, she became the first woman from the Gulf to earn a PhD in biotechnology (from Cambridge), served as a visiting scholar for five years at Harvard, and co-founded the nonprofit Diagnostics for All, dedicated to creating low-cost diagnostic devices for the developing world. She is winner of the Makkah Al Mukaram prize for scientific innovation and is a 2011 National Geographic Society Emerging Explorer, a 2012 UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for Sciences (the first Saudi woman to hold the role), and a devout Muslim who prays five times daily, starting at 4:30 am. Sindi was at PopTech this year to promote her latest endeavor, the i2 Institute, which launches in November to create an ecosystem of entrepreneurship and social innovation for scientists, technologists, and engineers in the Middle East. In essence, she is out to stem Mid East brain drain and cultivate more scientists like herself—who see science as a humanitarian mission, not, as she puts it, a means for earning “money, publications, and a good job.”

Or take 2012 PopTech Science Fellow David G. Rand. At 30 years old, Rand’s academic CV is six pages long, due to the awards, honors, journal papers, popular articles, lectures, and degrees he racked up before accepting an assistant psychology professorship at Yale for 2013. At Harvard, where he received a PhD in systems biology and is now on a post-doc, Rand studies cooperation, generosity, and altruism, combining approaches from psychology, economics, and evolutionary biology. His work integrates empirical observations from behavioral experiments with predictions generated by evolutionary game theoretic math models and computer simulations. Rand has been named to Wired magazine’s 2012 list of “50 people who will change the world” as well as the AAAS/Science Program for Excellence in Science, and his work has been featured on the front covers of Nature and Science—again, before becoming an assistant professor. He also leads an electro-punk project called Robot Goes Here, signed on Infidel Records.

Or take 2012 PopTech Social Innovation Fellow Bryan Doerries. Doerries is the founder of the New York-based Theater of War, which presents readings of ancient Greek plays to service members, veterans, caregivers, and families to help them talk about post-traumatic stress disorder and other challenges faced by military communities. The productions are not just readings of canonical plays by prominent actors; they “begin with the first line and end with the last [audience] participant speaker,” explains Doerries. In other words, they catalyze conversation among vets and their loved ones about the wounds of war. In 2009, the Pentagon did the unusual: it gave $3.7 million to Theater of War to visit 50 military sites and stage readings of Sophocles’s Ajax and Philoctetes for service members. This summer, Doerries staged The Book of Job, starring Paul Giamatti, in a 2,000-seat mega church in Joplin, Missouri, on the anniversary of the tornado that wrecked the town. It was an appropriate selection, given that the biblical story begins and ends in a storm, is about a man whose life is upended, and who questions why he is made to suffer.

Increasingly, fellows like Sindi, Rand, and Doerries are what PopTech is banking its future on. Under Zolli and president Leetha Filderman, whose previous work was in cutting-edge AIDS patient care, PopTech has invested in 110 fellows from 104 countries since 2008. This year, the Rockefeller Foundation has provided funds for the Bellagio/PopTech Fellows, the first class of which will include four people (artists, scientists, designers, technologists, or social innovators) who will conduct a two-week project on big data at the Rockefeller Foundation’s luxurious Lake Como residence.

Nice work if you can get it, you may think. But the idea behind these fellowships, says Filderman, is not just to support people of promise and to provide them recognition and connections, but to create a “global innovation network”—or in Zolli’s words, “to bring together people who are edge innovators and give them time to develop a new shared vernacular.” The aim of this new shared vernacular may seem fuzzy, but it is highly ambitious. Since PopTech moved six years ago from being an annual conference to a “foundation of the future,” as Zolli calls it, it has sought to make live the network theory fashionable in technology, social sector, and academic circles. Basically, its theory of change is that a network of interdisciplinary braniacs can create world-changing collaborations, discoveries, and innovations.

(Photo by Agaton Strom for PopTech)

(Photo by Agaton Strom for PopTech)

“If you [a grantee] have a relationship with a foundation, it’s a hub-and-spoke connection,” says Zolli, adding, “The whole model of how funders work in the world is not terribly networked.” What PopTech seeks to create through identifying and supporting “edge innovators”— people working on the edge of one or more fields or in “silos of excellence”—is a network in which connections are happening among the spokes (innovators), not the hub (PopTech).

So far, PopTech has only a few examples of this kind of spoke-to-spoke collaboration, but they are good ones. Sarah Fortune, a 2010 PopTech Science Fellow and assistant professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases at the Harvard School of Public Health, for example, presented two years ago in Camden the TB research coming out of her lab. During her presentation, she said that the workload for studying the images of bacteria that cause tuberculosis was both expensive and time consuming to decipher—and that her research was stymied as a result. She asked onstage, “Is there an app for that?” In the audience was 2009 PopTech Social Innovation Fellow Josh Nesbit who introduced Fortune to Lukas Biewald, CEO and cofounder of Crowdflower. The crowdsourcing Internet company breaks large digital projects into micro-tasks and distributes them to workers around the world. (Crowdflower claims a current workforce of 3.5 million people who fulfill 2 million tasks every day.) Biewald heeded Fortune’s call. According to Fast Company, CrowdFlower enlisted 1,000 people to make 40,000 “trusted judgments” about TB images in two days, returning them with more than 95 percent accuracy and demonstrating the potential for crowdsourcing basic science research.

Another example of PopTech fulfilling its network ambitions is Project Masiluleke. The initiative uses mobile phone technology to help spread health information about HIV and AIDS in South Africa. Under Poptech, Project Masiluleke created a partnership including iTeach, the Praekelt Foundation, frog design, MTN South Africa, Nokia Siemens Networks, and the National Geographic Society. “To date, the project is sending out 1 million messages a day,” says Filderman. “It is a real cross-sector collaboration of technology experts and health care experts.” Seeded with $500,000 in funds raised by PopTech (which does not have an endowment), the project also helped incubate an HIV self-testing kit against considerable odds. Back in 2008 when Project Masiluleke launched, HIV self-testing without an in-person counselor was considered too dangerous in South Africa. But the Project Masiluleke group argued the benefits outweighed the risks, and provided community feedback to back up the claim—and then supported a home test kit developed by frog design. Today, HIV self-test kits are now available in South African pharmacies and drug stores worldwide. PopTech can’t claim direct responsibility for this intervention, but it was among the forces that made it possible.

PopTech has been privately accused of favoritism and of relying on a small, clubby network to identify people and projects to support. Zolli is the person largely in charge of cultivating the network; he is an enthusiast with a big intellect and a healthy ego. (The theme of this year’s Camden conference was “Resilience,” which happens to be the title of Zolli’s recently published book.) Yet for those on the receiving end of this favoritism, PopTech has been a godsend. For Doerries, the founder of Theater of War (whom Zolli met through their mutual literary agent), it has meant that he could go ahead with the offer to perform The Book of Job as soon as the Missouri government made the offer. “I called Andrew [Zolli],” says Doerries, and “almost instantaneously he said he could support the project” though PopTech’s new Impact Fund, which provided $10,000. “There was no review process, the board didn’t convene,” say Doerries, which meant he could get the production moving immediately.

Doerries admires PopTech immensely for its nimbleness, for the way its accelerates the work of its fellows, and for its ability to convene an annual conference that is not “intellectual vaudeville.” But, he says, “in the larger scheme, the verdict is still out. … Can they harness all these individual organizations and people and then point them toward major issues in the world without necessarily giving them money—and accelerate their ideas?”

Doerries notes that the built-out organization run by Filderman and Zolli is only a few years old. “What impresses me most about PopTech is how it lives its values,” says Doerries, “When Leetha, Andrew, and the board have an intuition about an idea being of impact, they don’t hem and haw… They give you either money or social capital to make something happen, and then they help you bring the idea to a much larger audience. I know of no other foundations that do that.”

For Sindi, whose chosen career is a multinational social innovator rather than an Ivy League academic, “PopTech is family. They understand why I'm doing what I'm doing.” She remembers after her presentation at Camden in 2009, Zolli and Filderman scheduled a morning meeting and asked how they could help advance her work. Sindi has returned to Camden every year since, and her Middle East social innovation accelerator, i2, is partly inspired by and modeled on PopTech. Zolli will be a keynote speaker at i2’s Nov. 16 launch in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and Sindi hopes to bring some i2 fellows to present at Camden in 2013.

“They are translational leaders,” says Zolli of people like Sindi and Doerries and other “deep tribe” PopTech Fellows like Erik Hersman of Ushahidi and Ken Banks of Frontline SMS. “They are the people responsible for the social glue that coheres networks. And I truly believe there are 10,000 of them around the world.”

Zolli does not claim that he can identify these 10,000 people and give them a leg up, but one gets the feeling that he certainly would like to. “We’re trying to de-risk new approaches,” says Zolli, “so we can hand them off to the Rockefellers, etc. We’re trying to affect deep, structural change.”

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Tamara Straus.