SPONSORED SUPPLEMENT TO SSIR

SPONSORED SUPPLEMENT TO SSIR

Innovating for More Affordable Health Care

This special supplement includes eight articles that explore new ways for social investors to spur innovations that create better, faster, and less expensive health care in the United States. The supplement was sponsored by the California HealthCare Foundation.

Lifewave was facing an inflection point in late 2010. The early-stage company had a technology promising more accurate fetal monitoring in obese and overweight women, whose deliveries now account for 60 percent of all births in the United States. These women have pregnancies with high rates of complications and C-sections.

Early Lifewave clinical trials had produced promising results. Technology experts, investors, and clinicians also viewed the product favorably. But the company was having difficulty raising the necessary funds to get through the regulatory-approval process.

The California HealthCare Foundation (CHCF) was contemplating an investment through its Health Innovation Fund. If a CHCF investment were to be successful in moving the company to the commercialization stage, the Medicaid program in California, which pays for half of the pregnancies in the state, could reap significant savings.

Lifewave was the Innovation Fund’s first for-profit investment proposal. The foundation team began with a review of the company and its “mission fit” with CHCF’s charitable goals. The CHCF staff engaged in a spirited discussion about whether and how this investment could drive lower-cost care and improve access for underserved populations, its criteria for investment. Once the proposal passed the mission-fit screen, the team would finalize the terms of the investment, in consultation with legal and investment advisors experienced in both technology investment and foundation impact investing.

In order to secure an investment from CHCF that could help get it through regulatory approval, particularly given the challenges the company had faced seeking capital from traditional investors, Lifewave was prepared to adhere to the foundation’s investment goals—to improve outcomes for obese and overweight pregnant women, the providers who care for them, and the publicly financed system that pays for much of the care they receive. After approximately four months of due diligence, CHCF invested just under $1 million in April 2010.

The foundation is among many organizations looking for ways to enhance traditional approaches to funding social innovation. What drives their entry into “impact” or “mission” investing varies, but it generally includes a desire to scale up and spread successful programs, align an investor’s assets with its mission and goals, and work with innovative efforts across the spectrum of nonprofit and for-profit organizations. Several US health care foundations are following in the footsteps of their philanthropic counterparts in housing, economic development, and education. They are developing ways to find, make, and manage financial investments in private sector companies that can help fulfill their charitable missions.

This article focuses on foundation investments as a representative sample of the wider realm of social investments with a market orientation.

THE BASICS OF MISSION INVESTING

Mission investing, often referred to as impact investing, refers to investments in revenue-generating nonprofit and for-profit organizations whose work is consistent with an investor’s charitable purpose and goals.1 The emphasis is on investments, as opposed to grants. Unlike traditional grantmaking, mission investors expect that the funds will be paid back—recycled for their charitable purposes, so to speak. These investments offer investors a way to advance their philanthropic missions while supporting enterprises that may be more likely to achieve sustainability and scale than the typical grant-funded initiative.

Mission investments can include cash deposits, bonds, loans, or venture capital and private equity investments in companies, and they can be made directly, through funds, or via specialized intermediaries. Some mission-investing programs are market-oriented, generating financial returns that are comparable with typical investments in an organization’s portfolio. Within the foundation world, these are typically referred to as mission-related investments (MRI). Other programs take more risk or accept lower returns than commercial investors would take, but they also have the potential to generate significant impacts and deep alignment with an organization’s mission. These investments are a subset of mission investing referred to as program-related investments (PRIs). With all forms of mission investments, foundation social investors follow specific standards and regulations.

Social investors are exploring mission investing because they have experienced “successful” pilot projects that never made it beyond the initial site and often didn’t continue once the grant period was over. Although grants are the right tool for much of the work of social investors, fundamental limitations and challenges exist to scaling and sustaining organizations whose primary “fuel” consists of grants.

Moreover, many of the innovations that social investors care about are in the for-profit sector. This dynamic is particularly true in health. Whereas government pays for about 47 percent of health care delivered in the United States, private sector institutions deliver the vast majority of health care using technologies, devices, and tools that for-profit companies develop. In part because of health care cost escalation, health reform, and other forces, experienced innovators and investors are increasingly focusing their energy, capital, and creativity on developing solutions that ensure high-quality, lower-cost health care, as the articles in this supplement have demonstrated.

This growing pool of innovation and capital creates an exciting opportunity for social investors to reach out to new partners who can help tackle important health care challenges. These investors now have the opportunity to align their own knowledge and assets with this emerging breed of entrepreneurs and investors. In addition, the long history of health foundation work with the Medicaid and Medicare programs and public hospitals offers a window into what it will take for innovative technologies and services to be successful as these public programs expand and evolve under health reform.

IMPACT INVESTING IN HEALTH CARE

What follows is a map of the emerging impact investment landscape among US health care foundations. The goals and approaches vary significantly, but the diversity among programs provides a sense of how those seeking to use investments to improve health have approached mission investing.

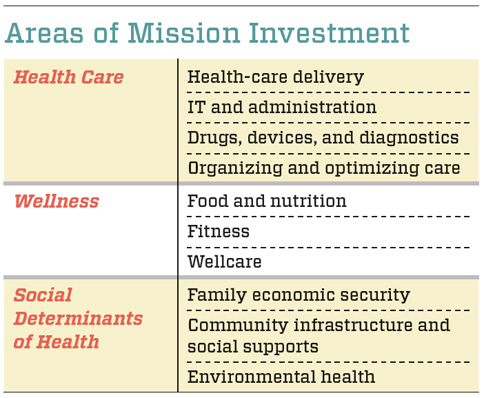

Interest areas extend beyond health care delivery to include the social factors that affect health (referred to as social determinants of health), such as poverty, education, air quality, and wellness issues like food and fitness. Opportunities for investment in both for-profit and revenue-generating nonprofit organizations exist in each of these areas, and each can offer social investors interesting opportunities to extend their traditional approaches to grantmaking and endowment management. (See “Areas of Mission Investment” below.)

Although health care foundations are working across a wide range of topic areas, impact investment projects are beginning to emerge under several common themes.

Lowering Investment Risk. Foundations can play an important role in lowering the risk for traditional financial investors, as the authors argued in the article that opened this supplement. (See “Funding the Safety Net” on page 4.) Their work can encourage investors—whose capital, expertise, and networks offer significant benefits—to support initiatives that might not otherwise meet the criteria for investment.

For example, The California Endowment (TCE), in collaboration with financial intermediary NCB Capital Impact and a diverse range of partners, established the California FreshWorks Fund, a public-private partnership loan fund created to increase access to healthy food in underserved communities, spur economic development that supports healthy communities, and inspire innovation in healthy food retailing.

In California, adults in neighborhoods with low access to healthy food options are 20 percent more likely to be obese than those with high access to healthy foods. The goal of the fund is to support supermarkets and other fresh food outlets in the “food deserts” of low-income communities. Through the fund, TCE and other social investors provide forms of debt and credit that remove some of the risk to commercial lenders and encourage them to provide major financing to projects.

Funding Specialized Financial Products. Several intermediaries, including some that operate largely in traditional markets, have worked in conjunction with foundations to create specialized financial instruments with significant health impact goals.

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation partnered with Community Capital Management, an experienced fixed-income manager, to find and purchase market-rate “community food bonds” that finance community facilities, schools, and community groceries. Inadequate access to healthy food in low-income communities and schools creates a critical impediment to good health, so the goal was to increase the supply of healthier, affordable food for vulnerable kids and their families.

Specific bonds supported a community garden where residents in an affordable eldercare center in Michigan could grow their own food; upgraded school lunch facilities to enable from-scratch meal preparation in a low-income school district in New Mexico; and an expanded facility for the Greater Boston Food Bank.

Establishing the Business Case. Recent advances in computing power, mobile technology, and networking have made possible an explosion of innovation that helps people track and manage chronic diseases more effectively. Although there is general agreement that these innovations can improve health, the business models necessary for them to reach sufficient scale have not been established. Social investors have an important role to play in developing the return on investment (ROI) cases—through studies, pilots, and business model development—that are necessary for new, cost-saving technologies to gain traction.

As one example, CHCF made a recoverable grant for a pilot with Asthmapolis, a company with a global positioning system that tracks where asthma episodes occur. The service allows asthma sufferers to manage their treatment more effectively, and public health workers to better understand the environmental triggers that exacerbate symptoms and contribute to health care costs. As part of this effort, CHCF and Catholic Healthcare West will be working with the company and its pilot partners to demonstrate cost reductions due to the technology and to explore business models with a range of payers and providers in the commercial, safety net, and government sectors.

Moving Innovation into New Markets. Traditional financial investors and their portfolio companies first seek to gain a foothold in the most profitable markets. This often leaves large but less lucrative markets, such as Medicaid patients or rural areas, without sufficient access to innovations. Social investors can create the financial cushion to test innovations and take them into traditionally underserved markets. Foundations in particular can play a crucial role in investment syndicates as strategic investors and intermediaries to help safety net providers and commercial companies work together more effectively.

Small and rural hospitals often cannot attract or afford qualified staff to supervise their pharmacies 24 hours a day. Avoidable medication errors are the result. Pipeline Healthcare (PHC) offers “tele-pharmacy” services that provide expert, remote supervision for these hospitals. The company is able to share a single pharmacist among several hospitals, increasing efficiency and improving compliance.

CHCF is contemplating an investment in PHC as part of a syndicate that includes the foundation, an investment firm, and a technology company. Through the venture, CHCF would help hospitals that care for underserved Californians to lower costs and improve clinical outcomes, and PHC hopes to prove its cost-reduction case and value to safety net providers.

Facilitating Lending. One of social investors’ simplest tools is below-market-rate loans to help health care organizations fulfill their charitable missions. Foundations across the country have provided working capital and construction loans to clinics that serve low-income people, at rates below what they would have been eligible for from traditional lenders. The loans allow community health centers to devote more of their resources to serving people in need.

For example, the California Primary Care Association (CPCA), in partnership with financial intermediary NCB Capital Impact, created the Emergency Working Capital Loan Fund in 2008. CPCA launched the program when a state budget crisis resulted in payment delays to community health centers that serve people on the state’s Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, which is the primary source of revenue for these clinics. California clinics were eligible to apply for up to $250,000 to cover working capital needs as they waited for payment. Clinics return the funds as soon as Medi-Cal pays, typically within two to three months.

Participants in the fund have included CPCA, Sutter Health Systems, Catholic Healthcare West, the Nonprofit Finance Fund, the Mercy Partnership Fund, and the California HealthCare Foundation. All the organizations have made funds available at rates ranging from 1 percent to 5 percent. When loans are blended together according to the proportion the funders have lent, the interest rate to the borrower becomes 3.25 percent, well below market rates. The fund has been renewed most years since 2008, and its total capital has ranged from $20 million to $30 million. The funding partnership will be expanded this year to include several new participants, including two foundations. NCB Capital Impact continues to do all the loan underwriting and servicing, and together with CPCA has created a loan guarantee fund to mitigate the risk of late repayment or default.

Another example is Playworks, a national nonprofit that has developed a program to bring recess back to public schools. As public school budgets are cut and recess is removed from the school day, safe and engaging play is disappearing from the lives of many children. With significant grant funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), Playworks expanded from its original base in Oakland, Calif., to more than 250 schools in 15 cities. Even with the grant funding, Playworks still faced a significant working capital deficit, because its payments often came well after the organization had incurred expenses. RWJF partnered with OneCalifornia Bank to meet this working capital need through a deposit that the bank used as collateral against which to administer a loan to Playworks so that it could “keep recess going” while waiting for school funds to come in.

LOOKING FORWARD

These are just a few of the ways that the tools of impact investing can improve health care. They represent creative thinking and a willingness to cross long-established boundaries between sectors in the pursuit of common goals. As the United States seeks to reform its health care system to both lower costs and improve access, such collaboration is vital. Foundations and other social investors have an important opportunity to serve as strategic partners in supporting the brightest and most creative entrepreneurs in creating lower-cost and more accessible models of care.

See the complete healthcare supplement.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by John Goldstein & Margaret Laws.