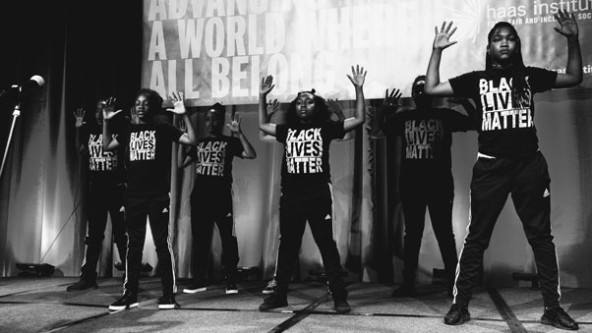

Destiny Arts Junior Company performs at the 2017 Othering and Belonging Conference by the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society. (Photo courtesy of Destiny Arts Center)

Destiny Arts Junior Company performs at the 2017 Othering and Belonging Conference by the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society. (Photo courtesy of Destiny Arts Center)

A few weeks ago, I had the chance to sit with a gender justice activist in a coffee shop in downtown Johannesburg, South Africa. Over cups of rooibos tea, she described the organizing behind #TheTotalShutdown and the strategic questions the movement faces in its negotiations with government. Gender justice activists in South Africa have long been wary of sitting down with government but are adapting new strategies in recognition of what government can do to drive large-scale change. Her experiences were a powerful, urgent reminder of both the strength it takes to lead significant social change, and the need to cultivate a collaborative space for leaders to process events and imagine new strategies with unexpected partners.

This is in the front of my mind because we, at the Atlantic Fellows for Racial Equity (AFRE), are closing out the first year of our fellowship program, in which 29 diverse leaders from the United States and South Africa gathered to deepen their work to address structural racism. It has been a remarkable experience, as well as challenging and humbling. The lessons we’ve learned will help us provide a more powerful experience for our future fellows and may be useful to others seeking to support social change leaders.

Transformational social change does not happen solely from large-scale protest movements like these, but it rarely happens without them.

The world is more connected than ever before, and so are the people challenging inequality and injustice. #TheTotalShutdown is an outgrowth of the worldwide women’s march, which helped spark one of the most significant movements for gender justice in recent decades, alongside movements like #BlackLivesMatter, protesting state-sanctioned police killings of unarmed black people in the United States, and #FeesMustFall, a student-led movement against the rising costs of universities in South Africa.

Transformational social change does not happen solely from large-scale protest movements like these, but it rarely happens without them. And while many people are focused on the work activists are doing, particularly when it comes to funding and evaluating successes, few are thinking about how to help them connect, learn, and collaborate with others who are similarly motivated, but are working for change in different ways and in different communities and contexts. Such partnerships can help create the insights, skills, and conditions for broad and lasting progress.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Connecting Social Change Leaders

AFRE is a direct response to this need. A year ago, we set out to create a space for leaders from different backgrounds and perspectives on racial equity to share ideas, build connections, and collaborate. We knew this would be difficult and complex, but the challenges were even more daunting than we expected.

Our program team and fellows mirrored the complexity of the racial equity field. Members of our community tended to gravitate to those with experiences and strategies similar to their own, and our program did not succeed at building generative connections across differences in ideology, race, ethnicity, and other forms of identity and affiliation. At times, the result was polarization rather than the cross-cutting discussion we hoped for, and in short order, we had our own total shutdown.

Moving forward required a willingness to face conflict and differences squarely, and learn from them. As social justice activist and lawyer Bryan Stevenson, says—we need to get into “proximity” with things that make us uncomfortable and perspectives that are difficult to hear. We weren’t perfect at it, but when we succeeded at stepping in, real learning resulted. We took away four main lessons from the experience, and they have changed every aspect of our work:

1. Focus on Vision

First, we needed to focus the fellowship experience on imagination and future-building, rather than on critique and deconstruction. This doesn’t mean discarding an analysis of our histories and experiences of violence and exploitation. But focusing only on current day realities can distract us from creating new visions and strategies for the future.

The animating principle behind AFRE is to help leaders who are working to dismantle anti-black oppression grapple with roadblocks so that they can construct audacious visions and effective strategies for change. Anti-black oppression is one of several structural forces that have shaped and distorted our societies, and we see it as an important entry point into achieving a larger vision of justice, dignity, and compassion.

But how do we engage in addressing deep racial inequalities while imagining a future that includes all of us? Our fellows have taught us that AFRE needs to be more than a space for analysis and collaboration rooted in resistance. We need to support leaders in forward-looking thinking, and build a self-sustaining network of resources and expertise the field can tap into for generations to come. This has required rethinking the sequence and content of our offerings to build in more time for inquiry and reflection on possibilities.

A panel of experts discuss “Racism in a Digital Age” at an event in Johannesburg hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation and featuring Atlantic Fellows for Racial Equity. (Image courtesy of the Nelson Mandela Foundation)

A panel of experts discuss “Racism in a Digital Age” at an event in Johannesburg hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation and featuring Atlantic Fellows for Racial Equity. (Image courtesy of the Nelson Mandela Foundation)

2. Look Out for Blind Spots

Second, we had to address major blind spots in our thinking about AFRE’s identity. Our program focuses on the United States and South Africa—two countries with a shared history of exploitation based on race, gender, class, and ability—and an exchange of ideas and experiences among black liberation activists. We aim to build on this rich history by offering a space for learning and relationship-building among a racially and ethnically diverse group of leaders from these two countries. Despite our best intentions, we missed important dynamics that undermined our ability to fulfill this purpose.

From the outset, our goal in creating a transnational program was to explore the global forces driving racial inequality. Although we grappled with this goal in macro terms, we underestimated how easy it is to replicate problematic power dynamics in the daily interactions of a fellowship program. We fell into a common pattern of centering US perspectives, thereby recreating inequities borne out of the relationship of Global North and South. As we spent time with our fellows, we also learned that South African and US-based fellows came to the program with different lenses on racial equity. Some US fellows approached racial equity through the lens of eliminating white supremacy, and its associated social, political, and economic privileges. Whereas South African fellows, coming from a country where the population and government leaders are predominantly black, focused their work on changing inherited power structures formed to subjugate black people.

A pro-black, pro-woman, pro-worker, pro-human world is one in which all of us flourish in the full complexity of who we are, with capacity to grow, learn, and change.

We realized we could not become a truly transnational program unless we focused on questions of experience, positioning, context, and analysis in more direct ways, and reconfigured our organizational structure and staff teams to match. For starters, we added more South African perspectives to our leadership team, and developed a process for ensuring that the language, facilitation, and underlying theories guiding our program resonate in both places.

3. Reach Beyond the Usual Suspects

Third, we had to confront our theory of change, and the importance of engaging diverse groups and players important to the movement. We originally focused on movement leaders, but in doing so, we missed the opportunities to connect them with others working to confront anti-blackness in its various manifestations—from both within and outside of the political system and social structures that perpetuate the status quo. Going forward, this means attracting people to our fellowship from institutions with power in society (including the government, finance, tech, creative, and health sectors), even if they do not define themselves as racial equity activists but are doing work that at its core contributes to achieving racial equity.

4. Listen and Learn From Difference

Finally, in creating a space for racial equity leaders to engage and collaborate, we learned how difficult it is to bring together people who are socialized in different experiences, cultures, and ideologies, even when they are united by shared motivations. We hadn’t anticipated the complexity of building understanding across different points of view and the designs needed to make it work.

So often, opening up ourselves to other points of view can feel compromising. Why should those of us directly impacted by racial inequality care about understanding the perspective and experience of people from historically dominant groups or with different ideological positions? There are several reasons this is important. Practically speaking, broad-based alliances are necessary to achieve the larger change we seek. Another reason is that it matters to our own humanity. It’s not surprising that the trauma of inequity, injustice, and diminishment shapes how we engage with others. But seeing the humanity in others and seeking to understand them, even when we disagree or have been hurt, is crucial to building a world shaped by joy, possibility, and potential. Because a pro-black, pro-woman, pro-worker, pro-human world is one in which all of us flourish in the full complexity of who we are, with capacity to grow, learn, and change.

This realization led us to focus the program on dialogue as a core pedagogy. We understand dialogue not as agreement, but as a process of learning across difference that is essential to achieving our social change goals. It also has meant building greater capacity within our program for facilitative leadership and restorative practices that build connection and understanding among diverse perspectives.

Moving Forward

Our first year taught us some basic—and difficult—truths about what it means to live our values. In responding to our fellows and to the moment, we have learned something that applies to all social change efforts past and present: that listening and learning from conflict and difference is vital for growth. It is also vital to building a bigger, more transcendent vision of the world we want and the strategies to get there. Our growing pains have helped advance a deeper and richer fellowship experience that better meets our vision and mission.

As I think back to my rooibos tea with the #TheTotalShutdown organizer, I didn’t have answers for the strategic questions she faces. I hope, though, that AFRE can be the kind of space where social change leaders can find answers to important questions like hers.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kavitha Mediratta.