It’s easy to look at global poverty alleviation work abstractly. I spend a lot of time reading about and debating the meaning of “social entrepreneurship,” “community engagement,” and other popular jargon of our field, far away from communities in extreme poverty. But it only takes a minute of visiting a small nonprofit in, say, Kibera, a Nairobi slum of 1 million people, to remind you that distance is the wrong reference point.

It’s easy to look at global poverty alleviation work abstractly. I spend a lot of time reading about and debating the meaning of “social entrepreneurship,” “community engagement,” and other popular jargon of our field, far away from communities in extreme poverty. But it only takes a minute of visiting a small nonprofit in, say, Kibera, a Nairobi slum of 1 million people, to remind you that distance is the wrong reference point.

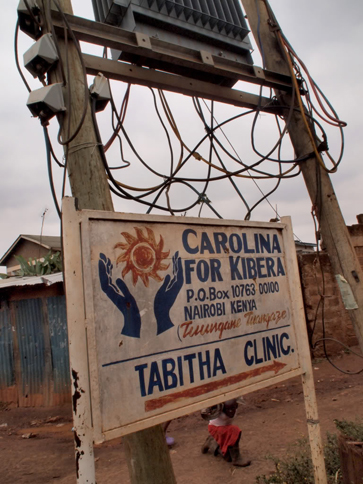

This spring, I met Rye Barcott on a book tour for his memoir It Happened on the Way to War: A Marine’s Path to Peace, and learned about Carolina for Kibera (CFK). Celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, CFK’s mission is to develop local leaders,

catalyze positive change, and alleviate poverty in Kibera. One of CFK’s core beliefs is that community problems require local solutions run by local leaders.

In 2000, as a 20-year-old, Rye was drawn to learn more about ethnic violence and spent a summer in a 10-by-10-foot shack in Kibera. While there, he met a nurse, Tabitha Festo, and a community organizer, Salim Mohamed, both of whom had powerful visions of how they could effect change in Kibera. Together, the three of them cofounded CFK with the broad goal of developing a new generation of leaders. The on-the-ground work in Kibera fell under the leadership of Tabitha and Salim. Rye worked from afar while he attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (CFK is a program of the Center for Global Initiatives at UNC). He continued to participate from afar while he served as a Marine in Iraq, Bosnia, and the Horn of Africa, and earned a master’s in business and public administration from Harvard.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Although Rye’s personal story is extraordinary, what attracted me most to CFK was its commitment to participatory development—the local community appears to have been the focal point of all that CFK has done from its founding to today, and that is apparent in its mission and operations. I believe, as many do, that one of the reasons so many efforts in global poverty alleviation have failed is that change hasn’t come from the community. CFK seems to walk the talk, and to put the community front and center in all things.

CFK’s entire staff in Kibera is Kenyan—many are from Kibera—and CFK’s office is in Kibera. The only full-time staff person in the US is Executive Director Leann Bankoski, who put me in touch with George Kogolla, the executive director in Kenya. George invited me to come to CFK’s office in Kibera when I visited Nairobi this summer.

After the adventure of finding CFK’s walled white and blue cement office (“drive to the Olympic Estate, it’s close to Chief Camp, park, and just ask someone to point you to CFK, everyone knows where it is”), my companions and I wedged ourselves into George’s back office. His office is attached to the small main room of the building, which was crowded with tables and computers where five staff members worked busily. Others bustled in and out.

George, soft-spoken and intent, spent a generous 90 minutes with us, describing CFK’s challenges and local orientation. CFK continues to grow its original initiatives (first two below) and has added new programs:

• The sports association teaches healthy life choices and promotes peace across gender and ethnic divides in Kibera. Over 5,000 children participate in the annual soccer tournament each year. (Chasing the Mad Lion is an upcoming documentary on the tournament.)

• The Tabitha Clinic is a community-based medical clinic and one of the few permanent structures in Kibera. More than 40,000 patients visit the new three-story clinic every year.

• Other programs for Kibera youth focus on reproductive health and women’s rights for 11- to 18-year-old girls; empower youth to talk about sex, HIV/AIDS, and reproductive health; and offer financial assistance to attend school. (Fifty percent of Kibera residents are under the age of 15.)

On one hand, the issues George discussed were unique to CFK; on the other, they seemed emblematic of executive directors and social entrepreneurs everywhere. “We are moving from a ‘doing’ to an ‘impact’ organization,” he told me firmly. He struggled to find local leaders. He was looking for a Kenyan to help with a strategic plan for Trash Not Cash, a community-managed solid waste management and recycling program that was intended to be a profit-driven social business. He was trying to create an effective program to develop local social entrepreneurs, who, he said, often didn’t understand the microlending concept. He had trouble transitioning local volunteers who received small stipends to full-time employment outside of CFK. He also spoke about fundraising hurdles and the challenge of increasing giving from Kenya.

While managing all these activities and many more, he hosts college student groups and western visitors like me. As we left the office to walk to the clinic, I met students and a professor from the UNC School of Social Work, who were conducting an intense few weeks of health research—just one of many university groups that have worked with CFK, including MIT and Stanford.

Woven through our conversation was the theme of community, which was certainly underscored by the office’s location. I can’t imagine a better place for an organization that “recognizes the youth of Kibera as resilient, wise, innovative, and eager to lift their community above the poverty and violence that plagues it.” CFK’s community focus promises to effect change that will stick. Seeing CFK in action gave me a much richer understanding of what community engagement really means.

Woven through our conversation was the theme of community, which was certainly underscored by the office’s location. I can’t imagine a better place for an organization that “recognizes the youth of Kibera as resilient, wise, innovative, and eager to lift their community above the poverty and violence that plagues it.” CFK’s community focus promises to effect change that will stick. Seeing CFK in action gave me a much richer understanding of what community engagement really means.

Ms. Ridley joined the Stanford Social Innovation Review in 2006 as publishing director. Previously she was group president at CMP Media, where she ran a division of technology publications, events, and websites. Ridley is also founder and board chair of Friends of Timboni Feeder School, a nonprofit that supports a K-5 school in Kenya. She holds a B.A. in political science from the University of Connecticut and a Masters in International Management from the Thunderbird School of Global Management.

Ms. Ridley joined the Stanford Social Innovation Review in 2006 as publishing director. Previously she was group president at CMP Media, where she ran a division of technology publications, events, and websites. Ridley is also founder and board chair of Friends of Timboni Feeder School, a nonprofit that supports a K-5 school in Kenya. She holds a B.A. in political science from the University of Connecticut and a Masters in International Management from the Thunderbird School of Global Management.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Regina Ridley.