Too often, people try to promote climate-friendly initiatives based on emotion rather than facts. Take green bonds—fixed income securities that are structured like conventional bonds, except that their proceeds go to environmentally friendly projects.

Data show that green bonds are an effective way to invest in sustainability, but their advocates are sometimes driven more by environmental passion than by observation-based forecasts of how the market will actually evolve. Skeptics, on the other hand, suspect that the green bond market never will be significant.

It’s true that understanding the evolution of this new market has been challenging. Green bonds still represent only a small percentage of the global bond market, although their issuance has grown rapidly since they emerged nine years ago. Governments, banks, and corporations issued close to $42 billion in green bonds in 2015. That number is expected to rise considerably in 2016, given current trends and the potential for growth, largely from municipal issuers in the United States and international issuers such as China and India.

For reasons like these, we believe green bonds will achieve mainstream acceptance in the next five years or so. But for this to happen, they will have to become less exciting, more “boring” and predictable, and more ingrained into the financial services system.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

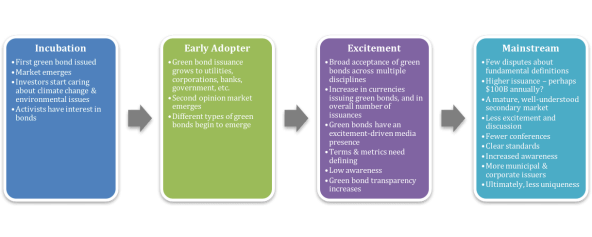

We believe green bonds are currently moving toward the predictability that investors want. They have already passed through what we term the “incubation” and “early adopter” phases, and are currently in the “excitement” phase. Their use is expanding rapidly, but awareness is still limited and several questions about standards remain unresolved. Governments, banks, and others can help speed green bonds’ movement into the mainstream by establishing clearer certification and ratings systems, issuing more of them, and educating the public about their financial and environmental benefits. These players’ participation in the global market will give investors confidence, and as confidence increases, the market will grow closer to becoming what we term “boring.”

Incubation Phase

The European Investment Bank, the World Bank, and Nordic investors invented green bonds around 2007 as a way of using fixed income investments (fixed payments on a fixed schedule) to mitigate climate change. Initially, they were the only issuers of this new financial instrument. Green bonds’ “incubation phase,” from roughly 2007 until 2010 or 2011, demonstrated that participants from all corners of the market could come together to reach mutually desirable goals. Issuers liked green bonds because they allowed them to diversify their financing sources and account for climate change risk while enhancing their image and increasing constituent awareness. Investors liked them because they were transparent, socially responsible investments with stable and predictable returns.

For the first time, finance professionals began to regularly discuss climate change issues, and climate change activists began to see green bonds as a way to funnel more money toward climate change solutions. They started to realize, as Sean Kidney, CEO of the Climate Change Initiative put it, that “the green bond market has the power to converge institutional investors and activists, and even make institutional investors into activists.”

At the end of this initial phase, annual issuance of green bonds had topped $1 billion for several years in a row.

Early Adoption Phase

Beginning in 2010 or 2011, green bond issuances grew beyond a few highly customized arrangements toward a much more scalable investment ecosystem. In roughly 2012, utilities, corporations, banks, state and local governments, municipalities, and others joined world financial authorities as issuers of green bonds.

Innovation and adaptation characterized this early adoption phase, which ran until around 2014. After a green bond structure proved it could attract sufficient investors in a certain market, new issuers tended to follow. For example, in July 2014 the DC Water Authority issued its first green bond, with a 100-year term—the longest for a green bond thus far—to solve a sewage overflow problem after the EPA mandated cleanup of DC-area rivers. This was the first green bond in the United States to use a second party opinion group, Vigeo, to assess its “greenness.” The model proved very attractive, and the $850 million in orders for the bond significantly exceeded its face value of $350 million. The bond’s long term, its use of a second opinion, and its popularity led other cities with similar environmental challenges to mimic its structure.

Excitement Phase

The green bond market entered the current “excitement phase”—marked by rapidly increasing issuance of and activity related to green bonds—around 2014, when issuance tripled from 2013. In this phase, the World Bank has issued over 100 green bonds in 17 currencies. Green bonds have spread from Europe to the Americas and last year entered Asian markets. China and India are issuing growing numbers of them. Oil companies and automobile manufacturers have also issued green bonds, as has Apple, Inc.

Conferences, scholarly articles, and media coverage around green bonds are exploding. Most, if not all, large investment banks have specific teams that focus on green bonds. Rating and review agencies are actively building systems for investors and issuers so that they can better evaluate the market and its inherent risk. For example, Standard & Poor’s is now officially rating green bonds. Rating methodologies are evolving rapidly and include new and strict standards for evaluating bonds’ “greenness.”

In this phase, we’re also seeing the beginnings of a secondary market, in which buyers resell green bonds to other purchasers, and the creation of the Green Bond Principles. Designed by a group of issuers, investors, and intermediaries, these guidelines establish the level of transparency and disclosure needed to properly issue a green bond. These structural changes are necessary to support green bonds’ massive growth. However, a number of matters remain unresolved. Agreement on what the label “green” entails, performance metrics, and many other standards need to be defined universally.

Mainstream Phase

To enter the mainstream, the green bond market will need to foster an increased awareness of what green bonds are and why they are an easy and beneficial investment. This could be achieved by offering green bonds to investors as part of a regular investment portfolio, building out green finance curricula in schools, or offering green bond education to people who are directly involved with fixed income investments. Financial service providers, colleges and universities, and others all can play a role.

Some commentators predict that annual green bond issuances may reach $100 billion in 2016. Our view is that this is likely a bit optimistic. But once achieved it may itself, as a commonly cited milestone in the industry, be a marker of green bonds entering the mainstream, and will most likely give investors confidence in the green bond market. Other confidence-inspiring indicators that green bonds have achieved mainstream “boringness” will be when oversubscription—demand for green bonds that exceeds the face amount of the issue—becomes normal and not notable, and when a vibrant secondary market gives them liquidity, meaning that people can sell them as easily as they can buy them. As the market enters the mainstream phase it, standards for green bond certification will also evolve and become clearer.

If green bonds make a successful transition from innovative novelty to mainstream investment product within the next few years, it will be greatly beneficial to our environment. We can assist in this transition by moving the market to a place where green bonds provide the predictability that investors seek. This will give issuers an opportunity to diversify their investor base and allow investors to hedge the risks associated with climate change. As investments in green bonds grow, quality of life and health will improve and governmental and nonprofit costs will decrease, ultimately leaving the world a much better place.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Abby Ivory, Paul F. Brown & David Chen.