The importance of engaging the private sector in efforts to address social problems is increasingly apparent. Wicked problems defy single-point solutions, and no single organization or sector working in isolation can solve them. This widespread understanding is matched by a growing number of businesses exploring the integration of social impact into their core strategies. “We’re seeing companies interested in moving from chipping away at problems to solving them,” as Tom Murray, vice president of corporate partnerships at the Environmental Defense Fund, put it. “If you are talking about ... climate change, over-fishing, or deforestation, no one can push solutions on their own—it will take collaboration across industries and supply chains. And these efforts are business driven, not driven by values or altruism.”

Janet Webb, CEO of the California-based timber company Big Creek Lumber, echoed this sentiment as she framed the motivation for her company to join a nascent social impact network of conservation groups and land-owners to effectively steward Santa Cruz mountain forests. For Webb, participating in a social impact network is about being “at the table” and having an opportunity to reframe what good land stewardship looks like: “Getting involved was more concern-driven than anything else,” she said. “We feel strongly that responsible resource utilization is a critical component of region-wide land policy and that there are significant environmental benefits to procuring local products for local markets. If we do not participate, this perspective may be left out of these important discussions entirely.”

The steady drum beat for more cross-sector collaboration and the recognition of the importance of private sector participation raises a set of important questions for any social change leader focused on mobilizing an ecosystem to address systemic challenges: How can a network of groups and institutions, not just a single organization, successfully compel private sector organizations to be part of their effort? How can we shift the conversation about addressing social needs from one based on a moral imperative to one that reveals a market incentive? And ultimately, how can we design an aligned action network that delivers both business value and drives social impact?

These are a few of the questions we set out to answer in a recent study on the power of involving business in social impact networks. We identified and analyzed more than 50 social impact networks that involve both civil society and the private sector, scoured the current literature, drew on the experience of both of our organizations in supporting and facilitating these networks, and interviewed more than 20 practitioners with direct experience leading or participating in networks that involve companies.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

The exciting and encouraging news is that there is already a range of networks in operation across the globe, where the private sector plays substantive roles. We found cross-sector networks designed to engage global seafood supply chains in rebuilding depleted fish stocks, collective efforts to reduce deforestation, and collaborations purpose-built to surface new market-based solutions to building healthy and sustainable food systems, to name a few. The challenge going forward is enabling more organizations to meaningfully and effectively engage with the private sector. To reduce the perceived chasm between the social and private sectors, social sector leaders need the skills and courage to act as bridge builders. A more capable and confident social sector can make engaging the private sector a normal part of systemic problem-solving strategies.

What we came to understand was deceptively simple: If we want to see more cross-sector collaborations, we have to get better at crossing sectors. What this entails, at a very tactical level, is that social change leaders intent on recruiting the private sector into their network craft business cases that clearly articulate the value of engaging. A business leader needs to see a clear path to participation, sense how that participation will serve a high-priority business need, and feel confident that their commitment is both well-defined and tightly bound.

Sundaa Bridgett-Jones, a senior associate director at The Rockefeller Foundation, underscored the necessity for a clear “value prop” when she shared her experience courting a large multinational for the Global Resilience Partnership, a nascent cross-sector network focused on building resilience in communities throughout three crisis-prone regions in Africa and Asia: “We had almost a year of conversation with them, and in the end, the value proposition still was not hitting the mark. While it may sound engaging to have an open white-boarding session about how to partner, we have learned that with business, it does not work as well as having a focused ask underpinned by a clear understanding of why that ask would be valuable to us and the partner.”

Crafting a focused ask that makes explicit the value for all partners is the critical first step in any “sector crossing”—an often overlooked but sorely needed move—and it has four main components:

1. Describe the business value the network can deliver.

At the heart of any social impact network that involves businesses is a value exchange that gives both business and social change leaders a reason to make participation a strategic priority. Social change leaders have a better shot at engaging the private sector if they can provide value to companies, both directly to their core lines of business and indirectly by addressing their broader needs.

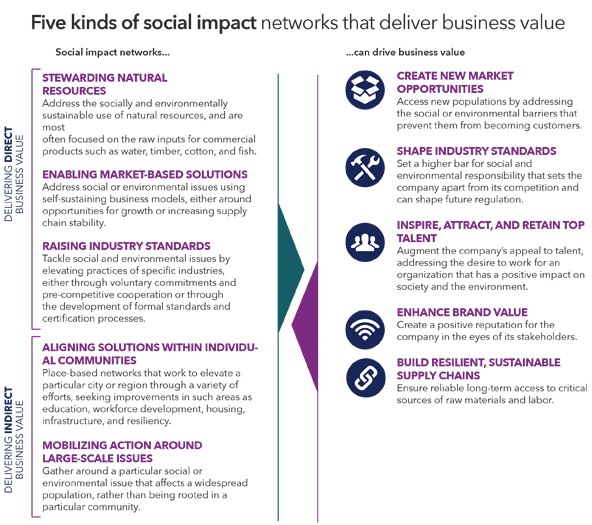

For instance, how would working collaboratively with a broad set of stakeholders to steward a region’s watershed serve a company’s interest? How would ensuring access to quality education for disadvantaged youth address the talent needs of a local business? Authentic participation by the private sector can accelerate a certain set of social impact goals—goals that also directly benefit a company’s core business. And conversely, the motivations for companies to join a social impact network fall into five kinds of potential business value (see chart below). Understanding this calculus for commitment is important.

Articulating the value exchange that makes explicit how a network effort can both make progress toward a social impact goal while delivering business value is critical, a point highlighted by Ryan Whalen, director for initiatives and strategy at The Rockefeller Foundation: “Before you approach a company, ask: ‘Are we ready to approach them, and do we have the right pitch for the right person?’ You don’t have endless bites at the apple. So make sure you make your case in an honest and serious way, not in an aspirational way. It demands a much colder calculus than most of what we do in social impact work.”

2. Discover the companies and individuals who would bring value as participants.

Knowing the right companies to engage and the right individuals within those companies can sometimes feel like finding a needle in a haystack. There’s often an assumption that the best portal into a company is through its corporate social responsibility (CSR) function, but it can be even more effective to ground the effort in a business unit where the strategic priority for participation is apparent.

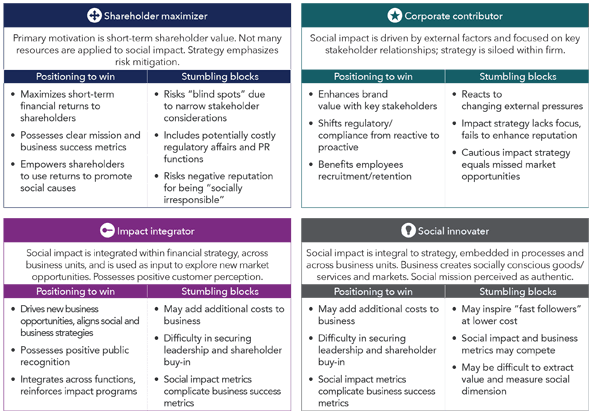

One way to identify the signal from the noise is to understand what type of company you’re considering. A 2015 Deloitte survey of the Fortune 500 mapped the distribution of firms across four typical ways that large companies relate to social impact (see graphic below). As you assess a company’s particular situation, look for indications that it might be an example of one of the four archetypes. While not an exact science, the traits of that archetype can help fill in the picture of the company’s motives and interests, and help you craft a more-focused ask and nuanced value proposition.

3. Define how a company can participate.

Once you sharpen the value exchange, set clear expectations of the minimum a company will need to bring to the table as a participant. Consider who needs to come to convenings, provide input, or make decisions. Think about the amount of time and preparation required by companies—and whether you will ask them to find creative ways to put their organizations’ non-financial resources to use.

Cheryl Dahle, founder of the Future of Fish—a bold experiment in cross-sector collaboration engaging entrepreneurs, industry players, and investors in seafood supply chain challenges—explained the importance of valuing participants’ time: “We are always trying to earn our entrepreneurs’ time. We want them to leave every meeting feeling that their time was well spent and they got something out of it.”

A naïve mistake is to see private sector participation only in terms of financial support—and to assume that businesses are like donors, willing and able to write blank checks in support of the network’s goals. Hal Hamilton, an experienced hand at recruiting companies to participate in the Sustainable Food Lab, a cross-sector network that surfaces market-based solutions to build healthy and sustainable food systems worldwide, reflected on the importance of widening the aperture of partnership possibilities when engaging a business: “There’s a greater possibility of real partnership if the project is material to the business, and you can make deeper impact by baking the sustainability goals into procurement and strategy. There’s a lot of money in the world, but there is not enough integration of sustainability and social equity goals into the way business happens. That’s where the gold lies.”

4. Craft the network story for a business audience.

Crafting a compelling story about what the challenge is, what the network wants to achieve, and how it will measure success is critical. At Monitor Institute, we call this “telling the story that’s not yet true.” It means creating a sense of what’s possible, architecting a larger story of change and impact that is bigger than any one organization’s story but still allows every member of the network to see themselves in it. To do this, frame the nature of the problem the network will address, the barriers to a solution, the stakes for overcoming those barriers, how the problem impacts commercial markets (such as its effect on natural resources, supply chains, talent pools, consumer attitudes, or government policies), the resulting business value that could be created, and what changes the network can achieve.

Future of Fish does this well. Its problem is that many fisheries are on the path to collapse. If a given fishery collapses, the result will not only entail significant environmental problems but also include lost livelihoods for the fisherman, fish brokers, grocery stores, and restaurants. To put it bluntly: an entire ecosystem is at risk. It’s a dire story that spawned a sophisticated set of strategies to address it: “The driving belief behind Future of Fish was that it was going to take more than one idea and one business to change a global supply chain,” says Cheryl Dahle. “We needed a platform that [acts like] a machine to continually invent new ideas and continually launch new businesses.”

This story, like many others we uncovered, is a testament to a new way of mobilizing a wider array of stakeholders to address wicked problems. And it’s a call to authentically understand just what it takes to do the “crossing” in cross-sector collaborations. As we build the skills to traverse sectors, we hope these networks will grow.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Faizal Karmali & Anna Muoio.