(Illustration by Sandra Dionisi)

(Illustration by Sandra Dionisi)

Walking into the conference room in fall 2013 to inform all of our colleagues that they were going to lose their jobs is a moment we will never forget. We had worked for weeks on what we were going to say. Lives were about to change, and we knew the reaction would be heavy. Coworkers arrived unsure and curious. We had never before had a mandatory staff meeting that demanded that coworkers cancel other meetings and rearrange vacations to attend.

The Power of Philanthropic Partnerships

This special supplement looks closely at the lessons the Orfalea Fund has learned about how to create effective partnerships with nonprofits, government agencies, and other philanthropies.

-

“Where Two Rivers Meet, The Water Is Never Calm”

-

Migrating a Partnership Ethos

-

The Pillars of Partnership

-

Accepting the Challenges of Partnership

-

Valuing Stakeholders in Early Childhood Education

-

Early Lessons Propel a Movement

-

Building Disaster-Ready Philanthropy

-

Strengthening Santa Barbara County’s Disaster Resilience

-

Choosing the Right Partners for School Food Reform

-

A Changing Landscape for School Food

-

Lessons From a Sunsetting Fund

-

When to Lead, Follow, and Let Go

-

The Gates of Hope

There was the normal buzz in the room as people settled in. But when our board chair arrived, you could see interest levels intensify. She began her comments by saying that we were entering bittersweet times. Scanning the room, we could see people’s faces change as they internalized the announcement. Our entire team formally learned that day what some of us had known for years: that we had mapped out the timeline for when The Orfalea Fund would complete its programmatic work.

There was never a question about whether we would “sunset,” so that part was not a surprise. Our founders had made it clear from the fund’s inception that it would have a limited life, but the details of the timeline had not been established. It would not have been advantageous to do so; our founders imbued the organization with a certain style of entrepreneurial opportunism. We were free to redefine ourselves and our grantmaking strategy as we went along; our culture encouraged the flexible approach we needed for striving to achieve our goals while helping to build leadership in our partner organizations. Had we established an end date at our inception, we would not have allowed ourselves that flexibility. So the premise of sunsetting had always been there, but the nuances of when or how went unaddressed until now.

A Journey Without a Guide

When a small group of us at the senior management level of the fund started down the final path toward closing, we were surprised at how little information about philanthropic wind-downs was available. A few foundations have been deliberate about sharing their strategies, including the Beldon Fund, Markey Charitable Trust, Atlantic Philanthropies, and AVI Chai, but the resources we found, while helpful, were specific to their circumstances and insufficient to guide us on our unique journey. There are hundreds of books on exit strategies available to for-profit enterprises. But in the social sector, no clear set of guidelines exists.

Partnerships played a key role in our founders’ business—Kinko’s, the business services chain—and that approach deeply influenced the fund’s philosophy toward philanthropy, seeking opportunities for collaboration and concentrated initiatives. But therein lurked an ironic complication for the sunset process: We had worked so diligently to foster strong and enduring relationships; how would we extricate ourselves from those connections with loyal coworkers, community nonprofits, government agencies, and other grantmakers? At the earliest stages of sunset planning, the directive from the founders and the board was clear: Do it with integrity, do it mindfully, do it efficiently, and do it strategically so that all parties end up stronger in the end. Our work in sunsetting had begun.

To that end we devoted intense planning and preparation. Our work continues to evolve, but we have learned valuable lessons, and our sense is that sharing what we have experienced and learned (missteps and all) may be of value to other organizations with similar wind-down goals.

To make it all easier to digest, we have broken up our experience into six areas, each of which needs intense effort (and each of which has come with a steep learning curve). Here they are:

- Aligning the fund’s finances

-

Strategizing about internal and external communication

-

Paying attention to personnel logistics

-

Engaging coworkers in the transition process

-

Purposefully changing the fund’s culture

-

Ensuring our partners’ and projects’ continuity

Aligning the Fund’s Finances

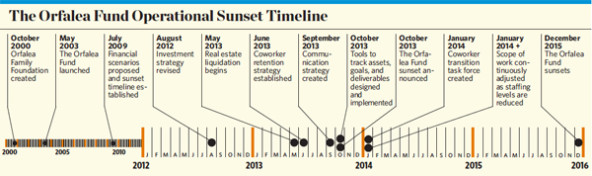

Four years before announcing our sunset to our colleagues in that conference room, we began midterm financial mapping, projecting various spending scenarios. We approached our donors and our board, offering three options for defining our fund’s trajectory: a desirable timeline, a curtailed timeline, or a strategic timeline. The desirable timeline was shorter than the planned duration of a number of our initiatives, but would allow us to spend at aggressive rates for five years. The curtailed timeline—a nine-year plan—was more conservative regarding assets. It would allow more time for the work, but would call for some compromises about what could be accomplished in scope and scale.

The strategic timeline scenario proposed a blend of the desirable and curtailed timeline concepts, using different strategies for different programmatic aspects of our work. It allowed inconsistencies to exist in our granting philosophy, prioritizing select initiatives over others. This method allowed for six additional years of funding. With donor input, the board approved the strategic timeline approach in 2009, and we believe it has served us well.

Importantly, intensive financial planning from that moment on has proven crucial to the process. We immediately linked our deadline to our balance sheet, which prompted a new degree of accuracy and urgency regarding cash flow. We deployed new cash-based financial tools to ensure that our calculations were precise. We aimed to project and track our total resources against all known or budgeted liabilities. Initially, we recalculated our assets semiannually, then quarterly, and now, in the home stretch, we review available assets on a monthly basis.

Three and a half years ago, we revised our investment strategy to transition completely out of stocks and into more predictable and conservative fixed-income bonds. About two and a half years ago, we began liquidating our real estate holdings, which enabled us to structure transfers of our properties to long-standing nonprofit partners, while also simplifying our list of assets.

Managing reserves has proven equally important. Although the work of our final 18 months was planned carefully, we knew to anticipate the unexpected and therefore we established a $500,000 reserve fund to cover any surprise expenses that might arise in the final months of the organization. If that money is not needed for expenses, it will be rolled into a donor-advised fund that can be used to sustain select aspects of our work.

Strategizing About Internal and External Communication

As our board prioritized a proactive communication strategy, our first vital decision, as the fund’s leadership team, was when to announce the sunset timeline and its implications. We deliberated long and hard about this. Our board anticipated that the announcement might divert the team and our partners from our core work. They feared that coworkers might abandon the organization. They worried about the bond with our partners. They were right. Everything changes when a sunset plan becomes public. Everything.

We knew that our work could not be completed in our now-limited time frame unless our entire team was involved in the conversation and could strategize together. So again we took a risk: we chose to share our timeline for completion 27 months before the close of the office. The planning phase leading up to that mandatory meeting was a time of intense learning. All summer, the office vibe was askew. Different coworkers knew different amounts of information. Managers participated in key conversations relevant to their initiatives. Yet in most cases, the full context could not be shared.

That meeting launched the process of rebalancing the organization and redefining who we were. Representing the culmination of months of preparation, we have to admit that it was a relief for some of us. But it was a day of shock for many others. Termination is uncomfortable, no matter the circumstances, so program directors and executive team members tried to deliver the news as thoughtfully and supportively as possible, conveying what the sunset meant, reiterating the founders’ and board’s original goals and intents, and articulating the high-level strategy for the completion of our work.

Immediately following the group session, members of the management team met individually with each coworker, reinforcing the primary messages and putting additional personal details on the table, such as a staff member’s projected termination date and severance package details.

Nonetheless, it soon became apparent that maintaining a unified, consistent message from all managers in an environment and time of constant change and charged emotion would be almost impossible. We learned early on to continually reiterate facts and confirm that all coworkers had heard the same information. We provided scripted responses to frequently asked questions and anticipated queries.

We used regular team meetings as opportunities to reiterate, clarify, and add to the common pool of knowledge. Though we recognize that we have been wrong on many variables along the way and strategies continue to evolve to this day, after that initial meeting, we shared what we knew when we knew it, and corrected or clarified in real time to sustain the culture of transparency we value and to keep our board, our management team, and the rest of our colleagues on the same page.

Immediately following our internal announcement, we launched an external communication campaign. Given Santa Barbara’s small-town nature and intertwined networks, there were many individuals in the community with personal knowledge of the fund, its donors, and its coworkers. Before the public announcement, we received inquiries from a few savvy partners who had deduced that a change was on the horizon, and so we realized that we had to act faster with a public announcement than we had planned.

We considered holding a press conference, but we struggled with whether our sunset was truly newsworthy, particularly since we were simply executing our original plan. Ultimately, we nixed the idea. Instead, we called or met personally with our closest partners, and then followed up with written communication to reinforce the message. We provided detailed speaking points for them to use in conversation with their boards, their staff, and others within their close networks.

Despite our best efforts, ever since the initial communications blitz, explaining the sunset timeline and its various ramifications has required constant reiteration in our community interactions.

Paying Attention to Personnel Logistics

Careful and intentional management of personnel matters, such as exit dates, retention incentives, benefits, and contingency plans, has been a vital component to our organization’s sunset. To begin, we established clear employment end dates (based on the requirements of each person’s work or role in the organization) and committed to notifying each staff member at least six months in advance if his or her termination date changed. In keeping with our values, we prioritized continuing comprehensive health care coverage in order to care for coworkers and their families holistically during a time of change.

To keep our staff members on until their end dates, we crafted retention incentives based on a set formula tied to specific end dates. As of mid-2015, 70 percent of our team has remained until planned exit dates.

To help mitigate the risk of premature departures, we also developed backup strategies for each coworker. We considered engaging consultants to fill in critical gaps so the organization would have sufficient capacity to achieve our programmatic and operational goals prior to the sunset, but we have not needed to do that so far.

One great irony of trying to retain staff members is our knowledge that in order to sustain the fund’s work in the community beyond the sunset, we need to support our coworkers, simultaneously, in identifying and pursuing new job opportunities. Doing this is a way to expand our reach in the sector beyond the life of the fund and leverage our significant investments in our people for continued community benefit. To that end, we engaged an outside HR professional to offer a résumé primer; we offer peer and management résumé review; and we accommodate coworkers’ time out of the office for networking, job interviews, professional development, and consulting opportunities.

Interestingly, our staff members requested open conversation around issues of job searches and end dates, and help moving on to future employment. Although somewhat unconventional, speaking candidly among coworkers about career explorations and job pursuits aligned with our culture. Yet despite our best intentions, the goal of balancing openness with privacy has been harder to maintain than we had hoped. At best, we have awkward conversations on the topic; at worst, loyalties have been questioned. Additionally, many coworkers find that they could be competing for the same jobs in the community, so a conflict of interest exists in sharing leads, forwarding referrals, and otherwise helping one another in the job search.

Engaging Coworkers in the Transition Process

Financial incentives may encourage retention, but maintaining staff engagement is a separate challenge. Despite months of planning and attempting to foresee all possible twists in the road, we remain open to new suggestions and input from our team.

Perhaps the most productive and valuable outcome of their input has been the creation of a transition task force charged with identifying coworker needs and gauging morale. Recruited internally and representing all facets of the fund, the task force has engaged with coworkers on a regular basis.

We anticipated that morale would naturally dip occasionally, but the task force has been instrumental in illuminating some of the causes of lowered morale. Most notably, those causes have centered on changes in our organizational culture and in individual expectations of what work should now entail.

First, the most common disappointment and demoralizing factor has been a sense of loss and frustration among coworkers who no longer feel the spark of working at a progressive, always forward-thinking organization. The fund is no longer engaging in innovation and structuring new powerful partnerships; instead we are wrapping up that work and shutting down operations. Our team members have been frustrated that they cannot support our partners financially and programmatically as we have done over the years.

Second, coworker exits have caused anxiety when workloads have shifted. In response, we eliminated most coworker-specific goals in favor of team or departmental goals so that everyone on a team would feel more aligned in working toward universal accomplishments.

Finally, the task force (not surprisingly) identified a need for stress management across the organization. Ultimately, members of the task force have focused on workplace wellness tactics to address that challenge.

Purposefully Changing the Culture

Our Pillars of Strategic Partnerships promote maximizing stakeholder empowerment, including the empowerment of our coworkers: our internal partners. (See “The Pillars of Partnership” on page 5.) Yet in the months leading up to the sunset announcement, most of our coworkers felt a keen loss of empowerment. Management meetings behind closed doors and whispered conversations in the halls intimated that something secret was going on. We dashed to get documents off the printer and abruptly stopped or altered conversations midstream when someone popped her head into the room with a quick inquiry. These were some of the first signs that our culture was changing, and the discomfort was palpable. In hindsight, this drama could have been avoided.

The sunset triggered an entirely different way of working. And so, in order to better manage a lot of work in a limited time frame with little margin for error, we introduced new management tools. Historically, we had avoided static strategic plans because our cofounders are such vibrant entrepreneurial visionaries, and experience had informed us that any documented plan would be outdated before it could be printed. But the sunset required a tightly defined strategy because changes in direction or focus could prevent us from completing our remaining work. We now employ highly detailed planning processes, with intricate reporting mechanisms. We have changed our culture to fit the times, committing to the diligent documentation of goals, progress toward those goals, and potential obstacles to reaching those goals—in great detail. It is an unfamiliar way of working, but the structure has allowed time to deliberate on our strategy, allocate our diminishing resources carefully, and map anticipated challenges to better forecast workflow and realistic accomplishments.

Perhaps the most difficult shift in our culture has been accepting and embracing the imperative to “let go” and let others step into leadership roles. Traditionally, we kept our antennas up and explored every relevant opportunity for potential collaboration, partnership development, or ongoing learning or sharing. Shifting to sunset mode compelled us to focus solely on the work at hand, completing what we started as best we could within the time frame, and sustaining the work after we are gone.

In a way, this is a liberating mandate. We no longer feel obliged to be constantly looking out for new opportunities. Instead, we have gradually turned inward, focused on our closest and most critical partners, and directed our attention to the three priorities established by our board for the final phase of sunsetting: Evaluation; A Legacy of Learning; and Sustaining the Work. We have never been so focused. Our vision has never been so clear. The hardest part is loosening our grip and letting our trusted partners take on the work and pursue their own vision.

Ensuring Our Partners’ and Projects’ Continuity

After we told our partners about our sunset plan, we explored next steps with each one on an individual basis. We wanted all of our grantees to remain strong leaders in their scope of work and be successful finding other funders to support their efforts. Thus, we sought to support each organization going into their next chapter. We looked at each grant individually, and discussed what aspects of the work needed to be sustained, and which would require financial and programmatic help to thrive.

In many cases, we made challenge grants to help organizations identify new funding sources. Additionally, we offered multiyear awards (sometimes in gradually decreasing amounts) to provide grantees with a few years of stability, allowing them time to develop relationships with other prospective donors.

We helped organizations identify other funding sources, both individual donors and other foundations, via personal introductions and large “friend-raiser” events, simultaneously using our voice to advocate for the value of the specific programs and the merit of funding them. Beyond funding, we formed oversight councils to help carry the burden of accountability and have worked tirelessly toward cultural shifts in school communities through student, faculty, staff, and parent engagement.

We found that determining the value of archived documentation, correspondence, and records, while mandatory for financial and audit purposes, required some existential and technical self-assessment. We asked: Who will want or need to access our history? Where should it be saved? What format (digital or hard copy) will be most helpful? Why save it at all? Our plan is to have our website serve as a primary reference for external inquiries so that other individuals and organizations can replicate the work of the fund, or tailor our successes in early childhood education, school food reform, and disaster readiness to fit their own communities and organizations.

What’s in a Name?

One of the earliest challenges we faced in managing the fund’s sunset was what to call it. While not as significant a problem as ending community partnerships respectfully and productively, or managing finances, or communicating with employees, it has been a vexing issue. What’s in a name? If we were going to extricate ourselves from partnerships we had spent more than a decade developing, we needed clear and consistent language to sum up what we were doing.

As the strategic vision for the shutdown shifted, so did our thoughts on that language: Would the work be taken up by another foundation (“conversion”)? Would it be better to use a literal description for the financial realities (“spend down” or “spend out”)? Would “retirement” be accurate (for the organization maybe, but what about for our people)?

We had found several examples of organizations that initiated a “spend down,” so early on, we adopted this terminology to describe the literal exhaustion of our assets. Internally, this term was used interchangeably with “spend out” but in the end, neither phrase really captured the essence of what we are doing. We let those terms fade, and for a while gave “retirement” a little air time. But that did not seem to fit the bill either, and ultimately, we settled on “sunset,” which seems to capture both the finality and the sentimentality of what is occurring. If nothing else, this subtly shifting nomenclature has been symbolic of the constant evolution of the process itself.

Eventually settling on the graphically emotional image of a sunset, we realize now that in so many ways, the fund we knew actually experienced “sunset” two years ago—when we announced our end date and the work of winding down began. That’s when our culture changed. That’s when our work changed. That’s when our tools and style changed. That’s when our vision and strategy changed.

Publicly and officially, we are shutting our doors on December 31, 2015, but for all intents and purposes, the sun began setting on the fund in the spring of 2013, and we have been in a steadily evolving twilight since then. Our hope, however, is that even when our twilight fades later this year, if we have done our job well, the sun will continue to shine brightly on the work being carried forward by our partners for many long days to come.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Catherine Brozowski & Tom Blabey.