If the rise of B-corporations—for-profit businesses with a certified social impact mission—is any indication, private sector companies have valuable roles to play in social change. What’s more, they have a desire to participate in collective impact efforts.

Yet for many nonprofits, local partnerships with businesses are a challenge. If the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors could find ways to collaborate with private businesses more effectively, imagine the potential for quickly scaling solutions that tangibly improve the lives of low-income people.

Before my role as director of collective impact at Living Cities, I founded Year Up National Capital Region, a nonprofit that empowers low-income young adults through careers and continued education. An important part of this work was collaborating with corporations to hire low-income students into internship programs.

Although I had formerly worked in leadership positions at General Electric, engaging companies in social change efforts taught me a lot about the experience of nonprofits trying to work with the private sector, why it is valuable, and how to bust through the roadblocks that impede these relationships.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Following is a framework to help nonprofits effectively partner with the business sector; it focuses on who, when, and how to engage businesses in social change.

WHO

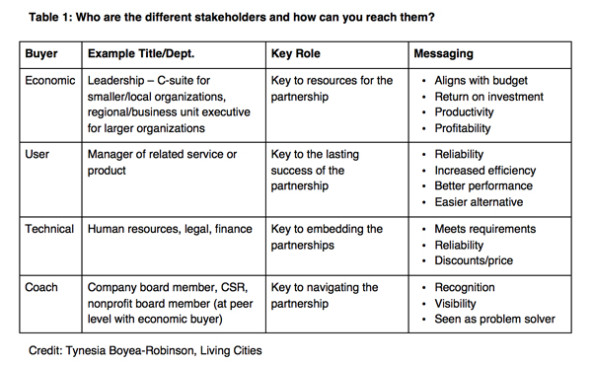

Like Miller Heiman’s “strategic selling” guide, which outlines the four types of stakeholders involved in making a buying decisions and which I’ve adapted to develop this framework, nonprofits must understand the four types of private-sector stakeholders who are involved in securing partnerships. Each has access to different resources, and therefore a different role to play in managing and deepening partnerships between the private sector and nonprofits:

- The economic buyer. This is the ultimate decision-maker, who has the power to release funds or kill the partnership; it’s usually one person but can also be a board. Economic buyers ask questions about overall strategy. To ensure that your partnership remains an organizational priority, use quarterly check-ins that focus on both the business and mission outcomes that result from the partnership.

- The user buyer. This person actually uses or supervises your talent or service, or otherwise stands to directly benefit from your partnership with the business. They are important to the lasting success of a partnership and judge the service based on the impact it will have on their specific duties. Because they’re the ones nonprofits will interact with most, effective engagement should include weekly to biweekly check-ins to gather ongoing feedback and proactively address concerns.

- The technical buyer. This is the gatekeeper, who often has the ability to say no to the partnership (often human resource, legal, or finance staff). They embed the partnership in the actual operations of any business partner and ensure that the partnership meets organizational criteria and requirements.

- The coach—your champion within the business, who helps navigate the partnership. The coach is the ally and advocate of your program or services. They should be at a peer level or above with the economic buyer and should provide the guidance they need to navigate the business’s cultural and political dynamics.

While working with AOL for Year Up, I met Balan Nair, AOL’s chief technology officer (CTO), who played the roles of coach and economic buyer for the partnership. As our coach, he helped technical buyers, such as human resources staff, remove legal barriers; he also helped champion the partnership through introductions to AOL’s leadership team (a mix of users and economic buyers). As the head of technology, IT, and network operations—and thus the economic buyer—he made important resource decisions; he also shared decision-making with other leaders who had discretionary funds.

Nair helped us time strategic asks for engagement (for example, after budget decisions), understand the culture of other departments and leaders (who had influence and who was open to trying new things), identify the best plan of attack, and navigate the overall partnership process.

(Table by Tynesia Boyea-Robinson)

(Table by Tynesia Boyea-Robinson)

Despite Balan leaving mid-way through our engagement with AOL, the program continued to grow stronger. The partnership became institutionalized within AOL, and we were able to expand the number of Year Up interns at AOL from three to 20.

WHEN

Good timing is critical to effective private sector engagement. Whether a prospective partner is in crisis or experiencing steady growth will make a difference in their willingness to partner with the social sector. Generally the more stable the company, the less likely they are to try something new.

Companies usually fall into one of the four stages of growth (also adapted from Heiman’s guide):

- Companies in trouble are more likely to take action in a partnership. They are usually experiencing change and interested in new ways to mitigate losses. In this stage, companies perceive a difference between where they are and where they want to be. To ensure that the engagement is successful, it needs to present a chance to close that gap.

- Growth-stage companies have many of the same characteristics as trouble-stage companies but are less resource-constrained. Since these organizations can afford higher-end support, it’s important to underscore efficiency and effectiveness, since they are often time-constrained.

- Even-keel companies are less likely to engage and likely perceives change as a potential risk. Effective engagement requires that partners prove that growth or trouble is coming, identify growth or trouble the company doesn’t currently see, or leverage other business partners.

- Overconfident companies perceive no gap between where they are and where they want to be. Companies in this category don’t feel like they need help and are unlikely to respond to engagement efforts from the social sector. Potential nonprofit partners will need to maintain the relationship, leverage their relationships with other businesses to share experiences, and look out for transitions into growth or trouble stages.

When I was running Reliance Methods, a consulting firm that advised companies on how to improve talent pipelines, one client wanted to work closely with Costco—an even-keel company that generates profits, invests in its people, and has little turnover. We waited to start a relationship until the company opened its doors in Washington, DC, because even though the business on a whole was stable, it was entering a growth mode in the local market. We knew they had to hire 200 people per store, including 100 as local hire obligations, so the opportunity was clear. We made the connection to Costco and the company relied on our support to meet the requirements of DC’s local hiring regulation.

HOW

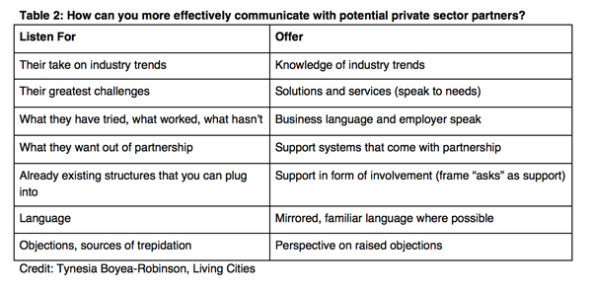

The third challenge is how to speak to businesses so that they respond. Here are five principles for engaging businesses:

- Speak as partner, not supplicant.

- Offer legitimate solutions to tough business challenges such as value propositions.

- Focus on how you will address their needs first.

- Know their numbers.

- Know the industry, the business, and your own assets.

In my time with Walmart’s Washington@Work effort, an initiative focused on giving DC residents skills and training needed for employment, social sector groups speaking to businesses in terms of the nonprofits’ own missions was a major barrier. Multiple community-based organizations were coming together to garner support for a pipeline of regional labor needs.

(Table by Tynesia Boyea-Robinson)

(Table by Tynesia Boyea-Robinson)

As this group of nonprofits involved in Washington@Work approached businesses to hire youth from their programs, they built a narrative around “turnaround youth,” emphasizing the potential for growth among young people through accomplishments like coming in for work on time. Yet this narrative would set off red flags for company leaders. We were communicating the value of the partnership in terms of the students instead of in terms of the business. Later, we coached everyone to focus on addressing the needs of the businesses themselves and on framing the partnership as a value proposition.

This group of nonprofits also often came in asking companies for donations or mentorship—as supplicants instead of partners—instead of showing their value with a diagnosis of the company’s industry. In the specific case of the supermarket industry, turnover is high, costing up to $10,000 per employee. Workforce development nonprofits can provide a talent pipeline of workers who have the desire and necessary skills to work the supermarket industry, and thus help reduce turnover rates and improve the bottom line. This framing as a value-add partnership, rather than a mentor-mentee relationship can lead to much more promising nonprofit-business relationships.

In exploring student/employee mentorship opportunities, nonprofits can frame the partnership as a professional development opportunity for volunteers from businesses. By giving them a chance to coach others, they will gain managerial experience, which also often increases employee loyalty and satisfaction.

Through my current work at Living Cities, a grantmaking collaborative of 22 of the world’s largest foundations and financial intuitions, I have seen many successful collective impact efforts build strong private sector partnerships. The Prepare Learning Circle, for example, is a group of five cradle-to-career collective impact partnerships that are explicitly focused on exploring what successful collaboration looks like in the context of workforce development and employment. And the Integration Initiative, a multi-city collective impact cohort focused on community development and economic mobility, has several initiatives focused on engaging employers to increase local hiring of low-income people. Finally, the Working Cities Challenge is a similar cohort of collective impact initiatives focused on improving the lives of low-income people, and they are exploring what private sector engagement looks like in mid-sized cities.

These efforts and others make it clear that building collective impact efforts in which businesses and nonprofits effectively collaborate can unlock benefits for both parties and create lasting social impact.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Tynesia Boyea-Robinson.