SPONSORED SUPPLEMENT TO SSIR

SPONSORED SUPPLEMENT TO SSIR

Innovating for More Affordable Health Care

This special supplement includes eight articles that explore new ways for social investors to spur innovations that create better, faster, and less expensive health care in the United States. The supplement was sponsored by the California HealthCare Foundation.

More than three-quarters of the world’s 5.3 billion mobile phones are located in the developing world. These increasingly powerful devices are proving to be a lifeline for people who need improved access to health services. The trend of using mobile phones for health—known as mHealth—represents an unprecedented opportunity for improving public health.

Much of the innovative thinking in mHealth is coming from programs that target populations outside the United States, often in developing countries. Now in a twist of fate, the innovations emerging from the developing world could prove to be a significant springboard for innovation in the developed world.

IMPORTING INNOVATION

General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt and his colleagues coined the idea of “reverse innovation” in a 2009 Harvard Business Review article, proposing that big companies must innovate in developing countries like India and China to survive.1 They argued that bringing innovations from the developing world to the developed world would both provide access to emerging markets and allow companies to pioneer new sources of profit in wealthy countries. The unique challenges of designing for low-resource environments in developing countries has fostered highly creative solutions.

One prominent example is GE’s portable ultrasound device. Traditional ultrasound machines cost upwards of $100,000, but a GE team in China designed a device for the Chinese market that plugs into a laptop and costs as little as $15,000. The difference was not just in the product’s price, but also in its target customers and uses. Instead of being designed for large hospital imaging centers and a range of uses, it was targeted to rural health clinics interested in spotting enlarged livers and gallstones. This drove further innovation in GE’s imaging products, including a handheld ultrasound that retails for less than $8,000 and is available in India and the United States, among other countries.

The Tata Nano is another example of reverse innovation. Although Tata designed the super-low-cost automobile for the urban Indian market, where it currently retails for about $3,000, it expects to export the car to other developing countries in 2011, and it has ambitions to enter the European market by the following year.

Mobile health applications from developing countries have the same potential to penetrate developed markets. In developing countries, these applications span a wide range of activities, including data collection, disease surveillance, health promotion, diagnostic support, disaster response, and remote patient monitoring. Experts predict that much of the mHealth innovation in developing countries will center around financial incentives and payments, as mobile money services targeted at those without bank accounts expand—for example, Safaricom’s M-PESA in Kenya and MTN ’s MobileMoney in various African countries.

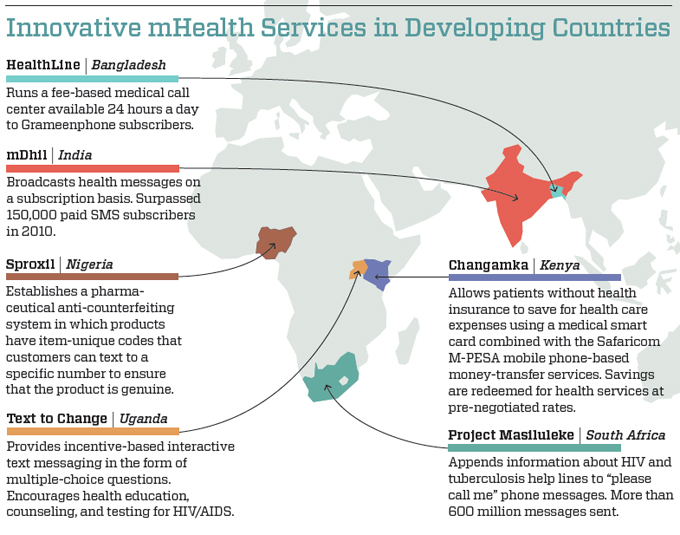

Programs strengthening health care delivery and data reporting have so far made up the most publicized mHealth technologies and programs. Well-known examples include TRACnet (Rwanda), Medic Mobile, MoTeCH (Ghana), and EpiSurveyor (working around the world). A range of other services present promising opportunities for learning. (A selection of services is described on the map, “Innovative mHealth Services in Developing Countries,” below.)

Much of the innovative work in mobile health has emerged in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The innovation in these places is a result of multiple factors, including targeted private and public funding, flourishing mobile markets, and significant health gaps. Several common themes have emerged from an analysis of the highlighted services: use of incentives or just-in-time information figures into each of these services; nearly all services involve some North-South connection between developed and developing countries; all involve mobile network operators, with roles ranging from passive communication network to active partner to service provider; and at least half have developed business models that suggest financial sustainability.

Among the applications most likely to have an impact in the United States are services that encourage positive behavior change and that remotely monitor patients. (Many of the other mHealth applications, such as those for data reporting and disaster response, do not map well to the United States context.) Phone-based solutions can potentially leapfrog existing approaches in the areas of behavior change and remote monitoring to lower the significant costs associated with unhealthy behaviors and with patient activity outside of clinical settings. Untapped opportunities exist to use financial or other forms of micro-incentives for behavior change, for instance. Although mobile money systems are unlikely to roll out in the United States as they have elsewhere, financial incentives do not require formal mobile money systems to function. Further, game-based approaches, such as those that Text to Change has developed, can be highly effective.

Although myriad mHealth programs are operating in developing-country markets, only a few prominent mHealth innovations in the United States have been imported from abroad. Among the most notable are Vitality GlowCaps and GreatCall Medication Reminder Service, both of which are working to improve medication adherence.

The stakes are high: Not following prescribed medication instructions adds an estimated $258 billion to $290 billion annually to US health care costs, or up to 13 percent of total health care expenditures.2 In particular, medication adherence is a major problem for the elderly, contributing to one in five Medicare beneficiaries discharged from a hospital being readmitted within 30 days.3

Vitality GlowCaps and GreatCall Medication Reminder Service do similar things, but work differently. The GlowCap device fits over commonly used prescription bottles, and it flashes and sounds when the time comes to take a pill. If the patient forgets, the product then uses an embedded wireless chip to offer a phone or text reminder, and the system can even alert a friend or family member, automatically call in a refill, and notify patients’ doctors about how well they’re taking their medicines. The device came several years after a similar product known as SIMpill was developed in South Africa.

A related service that works primarily through phone reminders and customer service is the GreatCall Medication Reminder Service, available as of 2010 on Jitterbug cell phones, which are designed to be particularly easy to use. The service helps the elderly remember to take all their medications at the right times. Mobile phone-based medication reminders have been used in various developing-world applications, including as early as 2001 in Cape Town, South Africa, as a cost-effective alternative to directly observed treatment, short-course (DOTS) for tuberculosis patients.

Another example is Text4baby, which provides free health tips to expecting mothers via text messages. Model programs such as VidaNet in Mexico and Mobile 4 Good Health Tips in Kenya provided the inspiration. With more than 190,000 users as of July 2011, Text4baby has been instrumental not only in highlighting the potential of mobile health to a broad population, but also in showing that it can operate at scale, something that has been done internationally in only a few cases.Text4baby used a public-private model to scale up its service, relying on a network of hundreds of partners, including financial sponsors, 18 mobile providers, government entities, and implementation partners in all 50 states to help ensure that the service can be offered free for everyone. The same approach can be seen among the mHealth programs that have scaled up globally. Many rely on complex public-private partnerships involving governments, international donors, and private entities.

None of these US programs is an exact copy of the global models that inspired them. This provides a lesson for organizations thinking about importing mHealth innovations. The goal should not be to copy programs exactly, but rather to adapt global innovations for the developed-world market. For instance, GreatCall’s US medication reminder service does not rely on text messaging, as tuberculosis programs do in South Africa, but rather on phone calls and a Web interface. As another example, Vitality offers several other services in the United States linked to the GlowCap product, besides the remote accountability feature that defined the SIMpill product in South Africa, including refill coordination with local pharmacies and support for alerts via social networks.

Models need to adapt to the wide differences between the United States and the developing world, not to mention between the United States and other developed nations. Aside from the variations in disease burdens and health systems, many countries have different cultures of mobile phone use. In the developing world, prepaid, or pay-as-you-go, models dominate; users commonly maintain active accounts with multiple providers; people often share phones; and users do not pay to receive phone calls or text messages. All of these factors affect the design of mHealth services.

LOST IN TRANSLATION

Although the United States has seen isolated cases in which global models have been adapted, overall imports of mHealth innovation have been limited. Quite simply, the various organizations that have an interest in mHealth—government, operators, health care providers, and others—too often have not adequately examined models outside the United States. Aside from this reason, several challenges have inhibited the spread of global initiatives to the United States, including a lack of evidence, unclear regulation, payment mechanisms, and market failures.

Lack of Evidence. The field is missing evidence of improved health outcomes, both globally and domestically. Early mHealth programs rarely included strong measurement components. A lack of evidence of impact on health behaviors or outcomes will prevent policymakers and many decision makers from investing in new technologies and programs at a significant scale. The good news is that the evidence is beginning to appear. Late 2010 saw the publication of two notable randomized controlled trial studies of text and mobile phone programs, and both showed significant improvements in outcomes. The first, the WelTel system in Kenya of text messages to help HIV patients stick to their medications, showed significant improvements in drug adherence and rates of viral suppression among those who used the service.4 The second study focused on WellDoc in the United States, and it examined a more comprehensive mobile phonebased diabetes management system for type 2 diabetics. It showed statistically significant improvements in blood glucose control levels among users of the WellDoc system.5 In addition, the Text4baby program is undergoing six independent studies, but the earliest data are not expected to be available until the end of 2011. Moving forward, the field needs for evidence to be gathered quickly and for both positive and negative outcomes to be shared.

Unclear Regulation. One thought leader interviewed during the course of this work suggested that strict domestic regulation is leading to the “export” of mHealth innovation. The framework for wireless health from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA ) is evolving, and it remains unclear how these advances will be regulated. The mHealth Regulatory Coalition (MRC) is advocating for greater clarity around regulatory issues so companies and investors can better plan for and fund innovation. The MRC is producing a guidance document to assist the FDA in formulating a reasonable approach to regulating mHealth technologies. It released the first part of this document in May 2011, with the final draft to be presented to the FDA in fall 2011. Many of the issues surrounding mHealth regulations are unlikely to be resolved before the end of 2011.

Payment Mechanisms. Health programs in the United States often look to payers—generally employers and insurers, both public and private—to support new services. But US payers have not shown an interest in purchasing mHealth solutions. To be successful in the United States, mHealth applications might have to appeal to a new group of payers, including consumers, health care professionals, facilities, and industry players like pharmaceutical companies. Multiple stakeholder groups might also collaborate to pay for a single service.

Market Failures. In most developing countries, governments sponsor mHealth programs and fund strong public health programs. In the United States, an employer-based system prevails, and so market failures frequently hamper the development of services that can deliver impact but for which private payers see no clear return on investment. Innovations in public health and prevention often stall out for these reasons.

LESSONS FOR THE FIELD

Based on extensive research of the existing literature and conversations with thought leaders and practitioners in the field, several lessons have emerged about how mobile health might become an area of successful reverse innovation.

Go Beyond Apps. Much of the current focus on mHealth in the United States is on smartphone applications, with a rapidly increasing interest in embedded wireless devices, such as those for in-home patient monitoring.6 But in the rest of the world, products and services rely heavily on text messaging and voice. The past five years in the United States have seen a rapid adoption of text messaging. According to Nielsen, people under the age of 18 send or receive an average of 2,779 texts per month. On the other end of the spectrum, those over age 65 exchange 32 texts per month, still many more messages than in past years. These numbers suggest an opportunity for text messaging solutions. In addition, voice communications have been used for largescale health hotlines in Mexico and India, and interactive voice-recognition systems have supported community health workers in Pakistan.7 Although smartphone applications might represent the bleeding edge, simple text and voice represent powerful tools with almost ubiquitous reach.

Target the Underserved. In the United States, the underserved are described in various ways: the rural and urban poor, the uninsured, the underinsured, the Medicaid population, and the undocumented. Underserved US markets often provide opportunities for a more direct mapping of applications from developing countries, particularly those from Africa and South Asia, given that mHealth programs often target the poor or those who serve the poor. Like poor populations in developing countries, the underserved in the United States are more likely to use prepaid mobile phone plans, share technology, rely on voice and text over data, and own more basic handsets. Effective programs, particularly those that emphasize behavior change, understand the culture of their users.

Engage Smaller Operators. The largest US network operators—AT &T, Verizon, and Sprint—have all indicated an interest in exploring their roles in mHealth over the coming years. These three operators support 250 million users, not including the pending merger of AT &T and T-Mobile. Nevertheless, they do not target specific markets of the underserved—urban youth, the elderly, and immigrant communities—like the providers that focus on prepaid services. Among the largest operators with the prepaid model in the United States are Cricket Communications, Boost Mobile (Sprint), MetroPCS, and TracFone. Smaller operators like these could provide mHealth services to their customers as something that adds value, and in the process they could attempt to increase usage of voice and data services. Developing countries have already seen this happen. Many operators have recognized that providing value-added services is one of the most effective ways to retain customers in a hypercompetitive business without service contracts. Examples of such services include mobile money services; HealthLine from Grameenphone, Bangladesh’s largest mobile network operator; and life insurance with the purchase of a SIM card, a product that both Tigo and MTN have launched in Ghana. Just as in the developing world, mobile health services have the potential to build and retain customers among smaller providers in the United States.

Mix Digital with Tactile. The next generation of innovations in mobile health will not rely just on the point-to-point communication capabilities of phones. Rather, they will integrate the digital with offline products and services as well. For example, the X Out TB service, from a team of developers at MIT , deploys a specially designed urinalysis test strip with embedded numbers that are revealed only when patients who have taken their tuberculosis medications take the test. The numbers in turn unlock secure mobile phone credits, a novel micro-incentive. Similarly, Sproxil works with pharmaceutical companies to print a unique physical code on the label of each product. Consumers can text the code to a specified number in order to ensure that the product is genuine before they make a purchase. A 2010 study found that 70 percent of Nigerian antimalarial and antituberculosis drugs were ineffective, either because they were counterfeit or because they did not have a high enough dose of the active ingredient. Both X Out TB and Sproxil offer inspiration for developed-world services that mix the digital and the tactile to create the next wave of mHealth innovation.

Completely Rethink Business Models. Fundamental innovation requires new approaches to revenue generation. For example, many of the innovations coming online in developing countries will be linked to mobile money services. Changamka uses smart cards and the Safaricom M-PESA mobile money service to help Kenyan women save for safe pregnancy and delivery services. The United States does not have a strong culture of patients directly purchasing health services, as is common in the developing world, but the Changamka model has the potential to fuel any number of breakthroughs.

LOOKING FORWARD

International markets offer an important source of learning for developed countries. The technologies and business models emerging in developing countries have been introduced in low-resource settings to improve health care access and quality. These approaches have already begun to inspire mHealth innovation in the United States and other developed countries.

Some of this learning will be based on existing models, but much of it will borrow from innovations that have yet to be launched. Direct translation will remain elusive. Throughout the process, the adaptation of successful models to industrialized markets will require creativity, flexibility, and a deep understanding of the people who use emerging technologies.

The following people were interviewed for this research, which was supported by the California HealthCare Foundation: Aman Bhandari, US Department of Health and Human Services; David Haddad, mHealth Alliance; Brad Houser and Larry Atwell, Cricket Communications; Don Jones and Ryan Gorostiza, Qualcomm; Ashok Kaul, Wireless-Life Sciences Alliance; Patricia Mechael, Columbia University; Paul Meyer, Voxiva; Douglas Naegele, Infield Health; Josh Nesbit, Medic Mobile; Mitul Shah, West Wireless Health Institute; Al Shar, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Rodrigo Saucedo, Carlos Slim Health Institute; and Dane Stout, mHealth Regulatory Coalition.

See the complete healthcare supplement.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Jaspal S. Sandhu.