At Open Philanthropy, a funder and advisor seeking to do as much good as possible with our giving, we are investing in safely reducing incarceration in the United States. Incarceration is a large problem that implicates detailed and complex systems, as well as deeply entrenched social and political problems such as America’s history of racial subjugation. While it has traditionally been a small field (for a long time, there were fewer than five major donors invested), funder interest has increased over the past several years, and substantial new investments have begun flowing in.

New funders who want to support the best work in reducing incarceration want to know: Where is the right place to plug in? What pieces can we bite off, and how do we choose? What are the greatest leverage points? How do we ensure that our investments don’t make the problem worse? How do we understand our investments in relationship to others? And one of the most important and elusive questions of all: How do we “change the narrative” of the dominant culture to create a real demand for criminal justice reform?

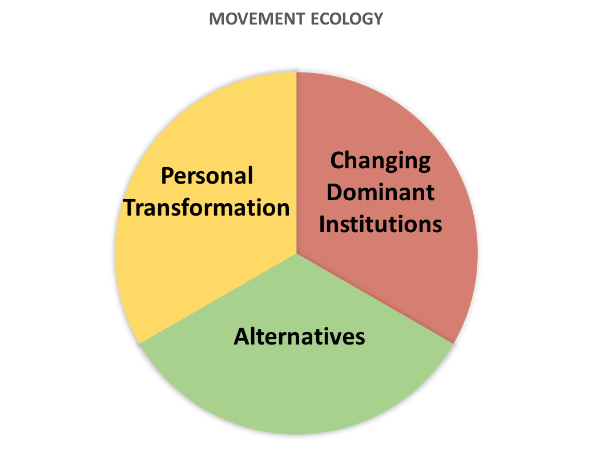

A framework called “social movement ecology,” developed by Carlos Saavedra and Paul Engler at the Ayni Institute, can help donors orient themselves to this issue and thereby better navigate these hard questions. The framework has deeply influenced my own work, giving me the confidence and clarity to draft more than $50 million in grant recommendations to Open Philanthropy over the past couple of years.

The classic criminal justice system map

Before talking about ecology, however, it’s worth addressing the classic criminal justice system map, which lays out the process by which a person moves through the US criminal justice system. This flowchart starts with crime on the left, then moves to pretrial, trials or pleas, sentencing, and prison or probation, with a lot of complicated forks in the road. At the end, the person lands “out of the system,” or achieves “reentry.” But in fact, for millions of people, there is no “out of the system,” only a revolving door.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Many donors and advocates have organized their work to target particular stages of the process and thereby disrupt this cycle. Attending to the intricate processes of certain parts of the criminal justice system flow (such as arrest, pretrial, or sentencing) can be good and useful, but we should be careful not to rely on this as a framework to orient overall investments in the field. We need to understand the processes of the criminal justice system, but not let them define our strategy. For example, in the farm animal welfare field, advocates do not frame efforts based on where a cow is in the slaughter process (such as on a truck, or a ramp, or the hook), but instead based on how the economic dynamics incentivize bad practices at all parts of the process. With respect to criminal justice reform, we need a framework that allows us to diagnose the forces driving, incentivizing, enabling, and habituating the current system, and build up the forces that can work together to create a new and better system.

Social movement ecology

For a large-scale social change effort that integrates many different kinds of work and gets at root causes, I have found that the most helpful tool is the social movement ecology framework described below. But first, a caveat: This model has layers of complexity, and I’m going to share a simplified version because I believe it is a useful tool. You may find reasons to disagree or identify things it leaves out. That’s fine. For now, hear me out on the major concepts.

First, think of everyone who identifies with a certain social cause, such as ending mass incarceration, standing within a very large circle. Now divide up the circle into three major theories of change—three ways individuals and groups try to make an impact on the world,—like so:

Personal transformation: This wedge includes people who make change by transforming individuals through approaches such as leadership development, bringing influential people to visit a prison, meditation practice for traumatized people most at risk of violence, or healing services for people directly impacted. (In my experience, this is the least-discussed theory of change in criminal justice reform work.)

Alternatives: This includes people who make change by building alternatives to the present institutions and cultures, showing us what the future can and should look like. Alternatives institutions and cultures offer a new vision for the future, today, by experimenting within new ways of doing and being. We can understand this work as building “off-grid” solutions that could become mainstream. Examples include restorative justice programs, credit unions, urban farms, or worker co-ops owned by formerly incarcerated people. The goal of alternative institutions and cultures is to model new relationships and ways of interacting within our social, political, or economic worlds (as opposed to something that offers a “less bad” option). For purposes of the ecology, you can focus on alternatives as prefigurative—a vision of the future we want to create for healthy and happy communities.

Changing dominant institutions: This wedge comprises those making change by reforming the structures that shape our lives under the status quo, such as governments and corporations. That includes changing laws and policies, replacing who is in power, transforming the dominant cultural narrative, and redirecting the priorities of major institutions. People in this wedge might include labor union organizers, advocates, protest movements, litigation shops, and elected officials.

Keep in mind that a person or institution may change their position temporarily or permanently. Where they stand is not a function of innate traits, but rather which theory of change drives current tactics.

Because so many people are trying to change dominant institutions, it’s helpful to further subdivide that wedge into three more specific theories of change: mass mobilization, structure organizing, and inside game:

Mass mobilization: People who make change by mobilizing people en masse to dramatize an issue and shift public opinion stand here. People in this wedge have the ability to “change the weather” (aka shift the Overton window), and to reshape the public’s conception of what is socially and politically viable. Often, this is a critical starting point for a movement that helps make later policy victories possible. Examples of movements that included mass protest mobilizations include the 1960s civil rights movement, the marriage equality movement, Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and the Dreamers movement. (If you are a funder seeking to help “change the narrative” with your funding, pay close attention to this piece! The next article in this series will delve deeper into how mass mobilizations present an opportunity for funders seeking broader culture shift.)

Structure organizing: This wedge includes those who make change by building an organized base of members to pressure decisionmakers around certain demands. This base could be any constituency, including people living in a certain community, students, people of faith, Latinxs, crime survivors, or any other group. This wedge includes labor unions, tenant associations, and neighborhood associations. Organizers in this wedge don’t change the weather, but they do “harvest the weather,” so to speak, by leveraging a changed public conversation to push salient demands.

Inside game: Mass mobilization and structure organizing make up the “outside game.” Those making change by working within government, or other elite or dominant structures, are part of the inside game. Those who leverage proximity to powerful decisionmakers and use expert knowledge to lobby for reforms—including litigators, lobbyists, elected officials seeking change, and bureaucrats and administrators at government agencies or universities—stand in this wedge.

A note on advocacy: In this framework, advocacy straddles the line between inside game and structure organizing. If the thrust of the advocacy is making a persuasive case with expert knowledge, we generally call that inside game. If a dedicated, organized base drives the advocacy, such as members of Sierra Club, it’s closer to structure organizing, though the lobbyists who represent Sierra Club still operate in the inside game.

You may ask where things like data analysis, journalism, and marketing fit in. The answer is that these are not theories of change, but rather tools that may be useful to one or more wedges. Organizations focusing on these things may be important to the overall infrastructure, but only to the extent that they assist those operating in the wedges to do their work. For instance, data analysis may help the inside game make its case for policy or assess the efficacy of an alternative. Journalism could help mobilize the public or help structure organizers build pressure on the inside game.

The three wedges that make up the changing dominant institutions area work together dynamically to open up space for change (mass mobilization), assert demands (structure organizing), and execute reforms (inside game). For example, the wave of protests following the Ferguson uprising ignited a national conversation on race and policing, which ultimately allowed structure organizations to successfully push for policies such as greater police oversight that addressed the needs of impacted communities. This wave of protests also impacted elections, driving the election of Kim Foxx as the new State’s Attorney of Cook County in Chicago. After winning the election as a movement candidate to an important inside-game office, Foxx is now responsive to the many structure-organizing groups that supported her election and now provide her with political cover as she makes bold moves. Without mass mobilization and structure organizing, the inside game is less likely to achieve major reforms.

Across the movement ecology, people bring important capacities to the table, and through complex collaborations, they can achieve major social change victories. In this model, each of the wedges needs the others to win. But in practice, many people don’t see it that way. Groups and leaders regularly dismiss other slices of the ecosystem (inside-game people are “sell-outs,” for example, or personal-transformation people are “navel gazers”). This leads to movement fracturing and undercuts the ability of groups to collaborate in ways necessary to achieve the most significant changes. Understanding the ecology can help diagnose these conflicts and address them more effectively.

Transformational funding

So how can the social sector use this model? There are a lot of possibilities. In my experience, the ecology framework serves four main purposes:

- Mapping: For funders trying to figure out where to plug in, the movement ecology framework can help assess the wedges most pertinent to their organizations (based on our various institutional commitments), as well as identify groups and people whose leadership and campaigns could have the most impact. Understanding the ecological position of a grantee can also reduce the administrative burden of the grantmaking relationship.

- Diagnosis: When groups or leaders clash, the ecology can help assess whether that clash is interpersonal or a result of misunderstanding between different theories of change. (Pro tip: It is very often the latter). Once diagnosed, the rift is easier to heal.

- Strategy: The framework pushes the sector to build strategies that will accomplish its goals. As mentioned above, an inside-game strategy usually needs pressure from structure organizing and perhaps mass mobilization in order to overcome serious political obstacles to change.

- Collaboration: The ecology map helps illuminate which leaders and groups can best collaborate to amplify impact. The framework also assists funders in supporting collaboration by providing a basic common language for meeting and strategizing.

In sum, movement ecology is a powerful and flexible tool worth exploring.

My understanding of it continues to evolve, and I regularly find new ways to apply it, but here are some specific ways that the movement ecology framework has helped me as a funder:

- It has enabled me to have clear conversations with other funders, grantees, thought partners and colleagues about which wedges I am supporting and why.

- It has provided a framework for discussion about complicated strategic questions, such as: What does it mean to change the narrative, and how do we do it?

- It has allowed me to avoid putting undue expectations on a particular group to accomplish something that its theory of change was not designed to do.

- It has helped me identify sources of conflict between groups as clashes in theories of change, rather than personal conflict or unreasonableness.

- It has drawn my attention to strategic gaps that need to be filled, such as leadership development.

- It has helped me identify which partnerships with other funders I most urgently need to pursue in order to shore up under-resourced portions of the ecosystem.

- It has allowed me to assess the impact of initiatives, based on the theory of change they apply.

- It has focused my analysis on the sequencing of investments to ensure that different wedges in the ecosystem are ready to take and build movement momentum at the right time.

One of the most pressing questions for funders engaged in criminal justice reform (and many other areas of work) is how to change narrative and culture. (See Rashad Robinson’s recent essay on narrative published by the Haas Institute.) Without examining that piece of the puzzle, the movement will never hit scale. Impressive policy wins alone will not put us on track to end mass incarceration, successful local organizing strategies will hit a wall, alternatives will remain small and under-funded, and we won’t have enough people committed to the cause to drive change across society.

The next article in this series will explore this point, arguing that the mass mobilization (also called “mass protest”) wedge of the ecosystem has the power to quickly shift culture by creating broad political urgency for change. We think major donors significantly undervalue and misunderstand this area. The article will discuss how mass protest strategies work, including the civil rights movement and the movement for marriage equality. A third article will discuss how to apply funding that creates the conditions and supports necessary for successful and scalable mass mobilization.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Chloe Cockburn.