Impact investing, which promises both financial returns and intentional, measurable social returns, is attracting more and more money—most of it from private investors. Foundations are hard-wired for social purpose and would seem to be natural candidates for impact investing, but so far they are behind the curve. Today, foundations account for only 6 percent of the approximately $60 billion in total impact investments under management worldwide.1 In India, foundations account for an even smaller portion, just 2 percent of impact investments, according to a recent report by Intellecap, an India-based research and consulting firm.2

The bulk of impact investment has been made by private investment fund managers and development finance institutions, which together have put up more than 80 percent of the money flowing into impact investing. It’s not surprising that most private investors (55 percent) seek to earn “competitive, market rate returns,” according to the most recent J. P. Morgan impact investor survey.3 Another 27 percent aim lower but still hope to achieve returns “closer to market rate.”

Enterprises that provide social returns and are highly profitable don’t have much trouble raising money from impact investors. But enterprises with an unproven business model, or ones that focus on serving the poorest of the poor, find that the vast majority of these dollars are out of reach. These types of enterprises—capital-starved social businesses with strong growth prospects but little chance of producing market-rate returns anytime soon—are, however, ideal candidates for philanthropic impact investment. Deploying “repayable capital” in this way has distinct advantages. Social enterprises get muchneeded growth capital, and funders get some or all of their money back—sometimes with interest—to reuse for another social investment. And all of this can be done without having to achieve market-rate returns.

Perhaps nowhere in the world is the opportunity for this type of below market-rate impact investing more striking than in India. Nearly 75 percent of the country’s 1.2 billion people live on less than $2 a day, and much of this population lacks access to basic services, such as clean water, sanitation, energy, and education. Providing these services creates opportunities for social entrepreneurs to develop bottom-up enterprises, but few of these businesses will generate competitive market-rate returns, at least for the foreseeable future.

Take, for example, the solar lantern company d.light. The company was launched in 2008 to create a safe, nonflammable, and long-lasting light source for low-income consumers. It secured backing from leading impact investors like Acumen, Gray Ghost, and Omidyar Network, plus from more traditional venture investors like DFJ and Nexus India. D.light has sold more than 10 million low-cost lanterns in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. But the company’s rapid growth would not have been possible without the early support of impact investors willing to embrace the market risks involved in pioneering a product tailored to the needs of poor, first-time consumers and also willing to accept the possibility of below-market returns. For every d.light, however, many other social enterprises will never achieve market-rate returns.

(Illustration by Celia Johnson)

(Illustration by Celia Johnson)

Such enterprises deserve more attention from funders, says Indian-American entrepreneur and philanthropist Desh Deshpande. “Impact investing may not be the way to get great returns, but it’s definitely a great way to take a solution out to a lot of people and scale it really fast.” (Read “Q&A with Desh Deshpande.”)

The Right Rate of Return

The need (and opportunity) for some impact investors to accept below-market-rate returns is not always acknowledged by impact investing enthusiasts. Indeed, the first comprehensive global analysis of impact investing’s financial performance by the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and Cambridge Associates largely argues the opposite. The study compared the financial performance of market-rate-seeking impact investments and comparable conventional investments and declared nearly a dead heat.4 “The data show that market-rate returns are achievable in impact investing,” says Hannah Schiff, senior research associate at GIIN. “Impact investing could be a great way for companies to create positive changes in society and the environment while still producing financial returns.”5

Major financial institutions have entered the arena and are banking on the prospect of earning market-rate returns. Black- Rock, the world’s largest asset management firm, announced in February 2015 the launch of BlackRock Impact, a business unit dedicated to impact investing. Prudential committed to investing an additional $1 billion in socially responsible businesses by 2020. And Bain Capital hired former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick in April 2015 to found a new business unit that “will focus on delivering attractive financial returns by investing in projects with significant, measurable social impact.”6 For the most part, these investment funds target market-rate returns—on average a double-digit internal rate of return, a standard measure of profitability for private investments.7

But generating market-rate returns for investors isn’t the right path for all, or even most, social enterprises that provide useful, adoptable, new products or services to the poorest of the poor. A Monitor Inclusive Markets study of 439 “inclusive” businesses (those aimed at bottom-of-the-pyramid communities) in nine sub- Saharan African countries found that only 32 percent were commercially viable and had the potential to scale up significantly in size.8

The situation is similar in India, where impact investors have put $1.6 billion into 220 enterprises, with 60 percent of that amount going to just 15 investees. Moreover, 70 percent of all impact investments in India—most coming from outside the country—have gone to microfinance and financial inclusion businesses, where interest rates and repayments are fairly predictable. “True early stage funding is still not available and … getting venture debt is next to impossible from our [Indian] banking system,” according to a 2014 Intellecap report.9

That assessment echoes the conclusions reported in a Winter 2013 Stanford Social Innovation Review article, “Closing the Pioneer Gap.”10 “One of the most striking findings of our research is that few impact investors are willing to invest in companies targeting the poor, and even fewer are willing to invest at the early stages of the creation of these businesses,” wrote the authors. Willy Foote, founder and CEO of Root Capital, a global social investment fund, has dubbed this orphan zone for impact investing a “high-risk, low-return sweet spot.”11

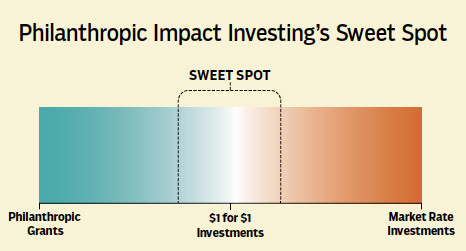

Think of the “sweet spot” for philanthropy’s impact investing as a gray zone, flanked on one side by traditional philanthropic grants that have no financial return, and on the other side by impact investors seeking market-rate financial returns. (See “Philanthropic Impact Investing’s Sweet Spot,” above.) The gray zone, encompassing small losses to modest gains, is where philanthropic money can and should concentrate its efforts. It is where a large number of financially underserved social enterprises attacking poverty, crime, homelessness, education, green energy, and other issues reside. In Kenya alone, where Root Capital has a major presence, Foote estimates that there are thousands of early-stage businesses “that have outsized potential for impact but still lack access to the financing and support they need to grow.”

In the United Kingdom, a recent report analyzed 426 closed social investment deals and found a total return of minus 9.2 percent—giving investors roughly 91 cents back on every dollar. Contrary to standard investment measures, researchers found that number encouraging. “It would be disingenuous to interpret this as bad,” concluded the report, The Social Investment Market Through a Data Lens.12 “This high level of capital preservation suggests that the social investment market is indeed investable.” And it underscores the opportunity for philanthropy to chart new ground by deploying more repayable capital.

Matching Mission to Financial Returns

By embracing lower financial returns, philanthropic impact investors can support enterprises that are explicitly seeking to serve the most marginal populations. “As you come to the bottom of the pyramid, people don’t have money, so you can’t really build a highly profitable company,” says Deshpande. But by creating a social enterprise, even a marginally profitable one, “you get two big benefits: you can scale it to a large number of beneficiaries and also make sure that the solution is what they want,” because people are willing to pay for it.

By contrast, impact investors typically assume that it’s up to social entrepreneurs to figure out how to increase earned income to boost return on investment. The reality, particularly for most early-stage organizations, is that fine-tuning a business model takes time. Profitability may take years, if it arrives at all. Meanwhile, the pressure to hit financial targets can push a social enterprise to place profit ahead of mission. Philanthropy is well positioned to counterbalance a tilt toward profit by providing patient capital to create high-impact, sustainable enterprises that reap below-market returns.

Social entrepreneurs can smooth the way for such philanthropic investment by clearly understanding their own economics and where their business model sits on the investment spectrum. This assessment can shape the story they convey about their organizations, including a deeper understanding of the type of funding and funding partners they need to grow.

Perhaps nowhere in the world is the opportunity for this type of below-market-rate impact investing more striking than in India, where nearly two-thirds of the country’s 1.2 billion people live on less than $2 a day.

But not all social enterprises are even candidates for impact investment. Although some manage to cover a substantial amount of their operating costs from earned income, they still need grants to cover unmet expenses. Take One Acre Fund, for example, an organization that provides training, tools, loans, seeds, and fertilizers to 280,000 of the poorest farmers in East Africa. It covers 75 percent of its field operating costs out of earned income but uses grants to subsidize the remainder of its costs. An impact investment could force the organization to go “up market” and serve betteroff farmers to satisfy investors. “We know it will be a challenge to operate our field program without some donor subsidy,” says Matt Forti, managing director of One Acre Fund USA.

For those social enterprises that can make a good case for growth capital from impact investors, there’s a temptation—and pressure—to craft rosy financial projections to woo market-rate investors. In fairness to them, the untested business models pursued by many social enterprises make accurate projections all the more difficult. But if optimistic forecasts don’t pan out, these enterprises must spend significant management time identifying additional sources of capital. This is the situation faced by Acelero Learning, a pioneering for-profit focused on closing the achievement gap for thousands of pre-school children in Head Start programs.

Founded in 2001, Acelero raised $4 million in venture capital in 2005 after it had been awarded its first contracts to operate Head Start programs. Investors came forward, basing their decision on the premise that Acelero’s superior operating performance would lead to a regulatory change to allow the company to make a modest profit on Head Start grants. By quickly building its portfolio of Head Start contracts, Acelero aimed to become both a social and a financial success. The company delivered on its social bottom line, growing to $50 million in annual revenue over a six-year period while producing best-in-class achievement gains. But critical regulatory changes stalled in the US Congress, undermining Acelero’s original financial assumptions. Eager to grow in a new direction, in 2011 the company launched a separate business unit, Shine Early Learning, to market its programmatic innovations to the wider child-care and education community.

To satisfy investors who had first backed the company a decade earlier, Acelero set out in the spring of 2014 to restructure its debt. It completed that process in May 2015 with a $4 million program-related investment loan from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, repayable at a 1 percent annual interest rate. Henry Wilde, Acelero’s cofounder and chief operating officer, says the Packard investment “will give the company the flexibility to continue to prioritize pursuit of our social impact goals.” Meanwhile, early investors, like Ironwood Equity and the Kellogg Foundation, agreed to a financial return in the low double digits.13

Another example of a social enterprise that had to find a new business model in order to continue its social mission is Embrace. The organization got its start as a class project at Stanford University in 2007, when a group of graduate students were challenged to design a neonatal hypothermia intervention that cost less than 1 percent of the price of a $20,000 state-of-the-art incubator. It launched as a nonprofit the following year with a single product, the Embrace Warmer, priced at about $200.

After garnering evidence that its warmer helped to save lives, Embrace sought to grow, but its nonprofit status in India barred it from securing investment capital to build a sales and marketing force. So it split into two legal entities: a for-profit, Embrace Innovations, which could take on debt or equity financing, and the nonprofit Embrace, which owned the patent for the warmer and could continue to pursue grants. Embrace Innovations received startup funding from impact investor Vinod Khosla, who focused on long-term impact, not short-term market-rate gains.

Embrace Innovations controlled R&D, manufacturing, and sales to health institutions and government agencies that could afford to pay full price for the warmer. For each warmer sold, the for-profit paid a patent royalty to the nonprofit. Meanwhile, the nonprofit donated warmers to clinics that served the poor, offering technical training and support for health workers and families. If this arrangement sounds complicated, it was. “There were times when we’d both show up at the same hospital,” says Alejandra Villalobos, executive director of Embrace, the nonprofit.

The two-prong approach worked for a while, but then the organizations ran into trouble. Embrace Innovations initially relied heavily on contracts with the Indian government, says CEO Jane Chen. But a change in national leadership in 2014 froze government budget allocations to purchase the warmers just as the social enterprise was close to landing a major corporate investment. The budget freeze delayed contracts, and the investment deal collapsed amid a significant change in the corporate investor’s leadership, leaving Embrace Innovations in a difficult financial situation. With encouragement from Khosla, the company rewrote its business model along the lines of Toms Shoes to launch a line of US-market baby warmer products called Little Lotus. According to the plan, with each Little Lotus product sold, a donation would go to selected nonprofits working on newborn health.

In July, Embrace’s nonprofit arm found a new home, merging into Thrive Networks. The merger integrates the Embrace warmer into Thrive’s suite of durable medical equipment developed for emerging markets around the globe. “By pooling resources and sharing expertise, we can expand the scale and scope of our existing solutions and work to develop even more effective tools,” says Carrie Eglinton Manner, Thrive Network’s board chair and a senior executive at GE Healthcare.

There are many lessons for social entrepreneurs in Embrace’s rollercoaster ride, but one critical to the organization’s survival was that Chen’s original investors encouraged the social enterprise to experiment with new business models and to pivot in significant ways until it found the right one. “One reason we were so attracted to Vinod Khosla’s partnership was that he wasn’t about setting arbitrary metrics,” says Chen. “He encouraged us to look at the long-term vision, and to constantly run experiments to figure out what would work best, whereas other investors we talked with focused very much on cost cutting.”

The Path to Philanthropic Impact Investing

As the number of social enterprises in need of below-marketrate investment grows, philanthropy is uniquely positioned to become a leading source of patient investment capital. Rising to that opportunity, however, requires changes to mindsets, skills, and processes.

Philanthropists need to make room in their toolkit for the type of impact investing that takes the patient-capital approach best suited for most emerging social enterprises. Evidence from recent research reports shows that philanthropists can expect to be repaid most, if not all, of their investments, making money available for future redeployment. Philanthropists should not, however, expect these investments to generate market-rate returns.

But impact investing requires a set of skills from different grantmaking. Social enterprises that pioneer new business models for social change have a high level of trial and error. They struggle to build management teams and find a reliable customer base. All this adds to the capital requirement and calls for investors to take a long view of the possibility of getting a financial return on their investment. Some US-based foundations have created teams working on program-related investments that also vet and manage impact investments. But for most philanthropists, whether in the United States or India, managing social investments will push them into unfamiliar territory.

Regardless of the type of investment they make, funders should adopt a bottom-up approach that involves social entrepreneurs in helping to write their own deal terms, determining what amount of money can be repaid, over what time frame, and at what rate. This is not the way conventional investment agreements usually take shape. Deal terms are often set by the investors, who, when push comes to shove, may force social entrepreneurs to compromise social impact in favor of meeting financial targets. Giving social entrepreneurs a strong voice in setting the terms of the investment invites a conversation between the entrepreneurs and the investors about purpose and profit that otherwise might not happen.

The time is right for philanthropists to become more active impact investors. Whereas private investors may focus on finding businesses that can provide market-rate returns, philanthropy would do well to build its capacity to invest in the many sustainable enterprises that may never achieve outsized financial results but are capable of achieving some returns and significant social impact.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Michael Etzel.