An old and bad economist joke:

The Tooth Fairy and Santa Claus are walking down the street and see a $20 bill. Who reaches down to pick it up? The answer: Don’t be silly; there is no such thing as a $20 bill lying on the sidewalk.

What does this have to do with development? In the standard model of economics, firms generally work to maximize their profits—they adjust their pricing, enter new markets, access credit, hire expert advice as needed, and pick up all figuratively available $20 bills.

Can firms grow without any infusion of financial capital and without any change to laws, underlying economic conditions, regulations, or export opportunities? If they are doing everything they can to maximize profits, then perhaps not.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Policies, both big ambitious and grassroots ones, often try to help firms grow. The microfinance community, for example, focuses on microenterprises, which are typically one or zero employee “firms.” Many believe that the key to increasing jobs lies with small and medium enterprises, or even larger firms. Others argue that firms are likely already operating at their optima, given their financial and legal constraints, so free money exists only through structural changes—in legal institutions, financing, export abilities, etc.

Two recent randomized trials by Innovations for Poverty Action in Ghana (coauthored by Dean Karlan, Ryan Knight, and Chris Udry) and in Mexico (coauthored by Miriam Bruhn, Dean Karlan, and Antoinette Schoar) tested whether consulting services can help enterprises grow. In other words, with nothing more than advice, can small firms or microenterprises increase their profits? Or are they already optimizing, given their resources?

The answer is likely, “It depends.” But depends on what?

We’d like to know what you expect. First, let us tell you a bit more about the settings.

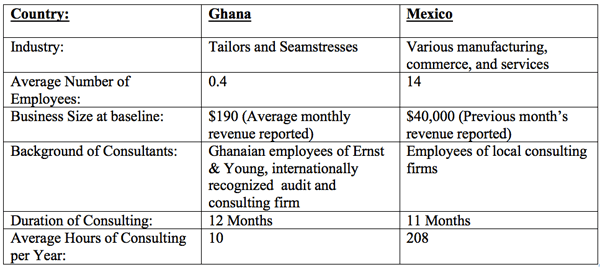

In Accra, Ghana, 160 urban tailors and seamstresses with an average of 0 to 1 employees were randomly selected to be part of the study. A subset of the sample was chosen to receive customized consulting work from Ernst & Young. The consulting began with lessons on the importance of record keeping, then used the new records to help the tailors calculate their profit margin on each item they sew, and taught them how to calculate a monthly income statement. Lessons on customer service and managing employees were discussed throughout. Each available tailor was visited 1 to 4 times per month, with each visit lasting 30 minutes to 1 hour. To gain an understanding of the interaction between management experience and credit constraints, some of these firms also were given a one-time cash grant of $160—more than 80 percent of the average firm’s monthly revenues. The remaining tailors were given only the cash grant or nothing at all. The study thus attempted to test three distinct theories about what impedes the growth of small firms: Is it a lack of management skills, an inability to deploy these skills adequately, or simply credit constraints?

The study design in Mexico advertised for subsidized consulting services to be provided to micro-, small, and medium enterprises in a variety of sectors. A random subset of the firms that replied were chosen to be matched with a local consulting firm that advised the firms on a variety of business practices, from better record-keeping to marketing. On average, enterprises had 14 employees, and met with their consultants once a week for four hours over a one-year period. The enterprise owner and consulting firm decided jointly on the focus and scope of the consulting services. The study thus jointly tested theories of microenterprise development along two closely related dimensions: whether a lack of management skill is a limiting factor in the growth of enterprises (a bit larger than those in Ghana); and, in addition, whether this knowledge can be conveyed via the provision of short-term consulting services.

In the summer issue of SSIR, we will discuss the results of these two studies in more detail. But here, we’d like YOU to predict the results. We are doing this because people often have preconceptions about solving poverty issues, and rigorous evaluations often challenge conventional wisdom. It’s always easy to say, “I told you so” when there is no clear record of what the predictions were; ideally, people could register their predictions in advance.

With this experiment, we also are taking a baby step toward a more ambitious idea—to have a market in predicting the results of randomized trials. Such a market would serve two purposes. First, it would allow stakeholders to stake their claim (pun intended) on their predictions and be held to acclaim when they are right or to have their opinions challenged when they are wrong. Second, such a market could help donors, practitioners, and policymakers make decisions about poverty programs, by engaging the market’s collective wisdom. (Think www.intrade.com, but for results of social impact interventions.)

So here goes. To make this survey tractable, we have lumped together outcomes and asked for broad predictions. Please vote which of the four possibilities is the outcome of the Ghana and Mexico studies:

Among those who provide the correct answers, we will randomly (of course) choose two winners: winner #1 will receive a free copy of Dean’s book with Jacob Appel, More Than Good Intentions, and winner #2 will receive a free, one-year digital subscription to the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Annie Duflo & Dean Karlan.