How should we think about impact investment, philanthropy, and the social economy?

This was the subject of our latest ReCoding Good charrette—one of a series of collaborative sessions around the use of private resources for social good. With the aid of several experienced investors, funders, and innovators in both philanthropy and impact investing, we realized that the time for defining these concepts has arrived.

Some people say impact investment is the next big thing in the production of socially beneficial goods and outcomes. The impact investing movement has just started to catch on; money and resources are now flowing in with the promise that a flood of further investment is to come. Talk abounds of a potential trillion-dollar marketplace in impact investment. Others believe that there is already an impact investing bubble, and that its current rate of scaling is unsustainable, as well as detrimental to it’s own long-term interests. This camp thinks there is more investment capital claiming the mantle of “impact” than there are investable enterprises, and points to the number of funds designated as impact investment capital and the number of conferences, papers, or media attention around it. One charrette participant noted, “Every single conference features an impact investing track. There’s no getting away from it.”

There was even stronger disagreement around the need to do something about this bubble. We discussed: How is this disagreement possible? Aren’t market bubbles inherently concerning? And shouldn’t the concern be even greater when the market is social goods versus new widgets? Is it possible that there are bad bubbles and good bubbles?

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

This apparent paradox is a result of there being two very different goals in impact investing. One set of investors—we’ll call them “social first” investors—is trying to use and attract return-seeking capital to build and scale markets for social goods. Their focus starts and ends with social outcomes (such as more housing, better health care, financial services for the poor) and uses the mechanisms of impact investing as means to these ends. This group seeks to invest in organizations that can reliably address social problems. Earned revenue and some financial return—not a market return, but some return—fuel the engines of social outcomes. The impact these investors seek is social.

The more ambitious, perhaps radical goal of the other set of impact investors is to take on all investment capital and make it more socially productive. Their vision is to change the mindset of investors in the traditional marketplace and draw greater amounts of capital to more socially positive areas. Ideally, traditional investors would adopt a social screen on their investments, directing capital only to organizations that generate a positive social return and dropping investments in organizations that offer no social return. This group is not interested in using financial tools to improve social outcomes, but in using social outcomes to change financial markets. We’ll call these “finance first” investors, as they seek to impact the financial systems themselves.

Both investor types have grand aspirations. The commonly used market estimate for “social first” investors, based on a 2011 JP Morgan study of five sectors of investment, is $1 trillion dollars by 2020. “Finance first” investors have their eyes on the $7 trillion in global assets already managed through social investment screens (and the tens of trillions in global financial markets beyond that). No one has yet put a stake in the ground on the size of the social impact that might be possible.

To-date, impact investing has attracted and held both groups. This is where the paradox of the bubble comes into play. The last few years has seen unprecedented success in building awareness of impact investing, creating new tools for deploying investments, and convincing skeptics that there is a huge pool of money at stake.

For the “social first” investors, a bubble could be trouble. Re-branding low-return investments as being impact-oriented (often referred to as “impact imposter” capital) will not solve social problems and may cause scorn, as results are slow and investment grade enterprises few.

For the “finance first” investors, who seek to change the mechanisms and norms of traditional capital markets, a bubble may be a sign of progress and influence, as attracting more and more capital is itself the goal.

These different attitudes about a bubble raise a key question: What should we count as impact investment anyway? Paul Brest put forth two criteria for impact investment: 1) The funded organization actually produces social impact, and 2) the investment reduces the costs of capital for that organization.

Calculating the cost of raising capital for any organization helps us see investments across a full spectrum of funding—from grant dollars (fully subsidized, labor intensive, expensive capital) to market returns (low cost capital with numerous alternatives). Brest noted that it is the impact criterion that remains murkiest, as neither philanthropy nor impact investing has yet developed widespread, meaningful metrics of impact within certain policy domains (for example, microfinance) or across policy domains (For example, comparing microfinance social returns with the green enterprise social returns).

Our discussion noted the differential between dollars that claim impact—those dollars actually in use (deals made)—and the even smaller percentage of deals that have a clear social purpose and a high risk-tolerance. A fraction of one percent of all foundation Program Related Investments (PRIs) involve equity investments; more than 99 percent of foundation PRIs—which might stand in as one proxy for “social first” investors—are relatively safe loans and loan guarantees. Equity financing is mostly available for risk-adjusted return investments, which the “social first” camp designate as the demarcation point from impact investing to regular investing. This demarcation point and the debate about a bubble clarified both the existence of two distinct camps within impact investing and the potential challenges of using one term so inclusively.

The practical challenge of a bubble is that it attracts too much money too quickly, before good measures are in place and good practices are known. Rapid growth will undoubtedly lead to major visible failures, which may turn off the spigot of funding or, worse, damage real efforts at social change and attract punitive regulation.

Redefining public good and repositioning philanthropy

The bubble discussion uncovered another tension about something much more fundamental: What is the role of philanthropy and what are social goods? These questions came to light as we considered the commitment to scale that shapes impact investing.

Impact investors look to the market as the key mechanism for bringing innovations to scale. If you can demonstrate that traditional banks can make a margin of profit from microfinance, then large banks across the world will get into the microfinance business. In this way, microfinance becomes available at much larger scale than any single, traditional philanthropist could achieve. In the “social first” camp of impact investing, the market is the key scaling strategy and the exit mechanism for early investors.

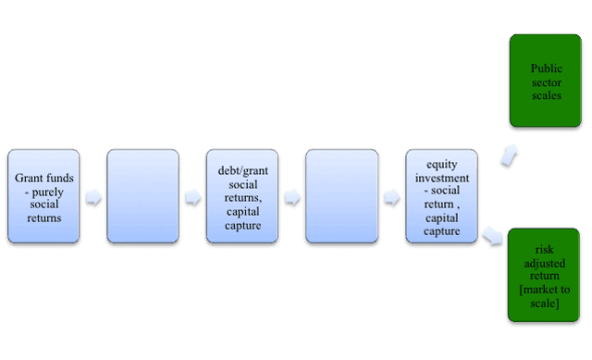

Figure 1: Markets as Scaling Mechanism

Figure 1: Markets as Scaling Mechanism

Philanthropy has also sought to bring successful ideas to scale, but the mechanism for doing so has been state or public financing, not the market. One conventional take on the role of philanthropy in a democracy is that philanthropic assets represent society’s risk capital: Let philanthropists, rather than state budgets and politicians, experiment with innovative social programs, evaluate these, and then bring the best of them to scale by having them taken over by the state. Carnegie’s libraries, Head Start programs, the 911 emergency number, and traffic safety lines are all examples of this.

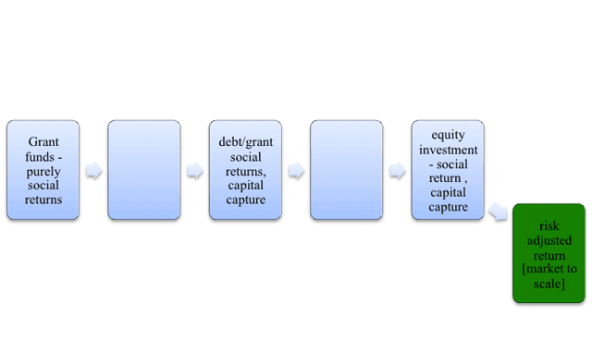

Figure 2: Markets and Government as Scaling Mechanisms

Figure 2: Markets and Government as Scaling Mechanisms

As philanthropy and impact investing continue their co-evolution, we now have two possible scaling mechanisms: markets and public sector finance. On what basis (and when) will we determine whether the appropriate scaling mechanism is a market (private finance) or a government (public finance)? In the past, this distinction—market based or government provided—has been core to our understanding of public goods. We must now ask whether it is the good itself that has some public value or if that value is simply determined by its financing mechanism?

These choices also hint at a changed understanding of philanthropy’s role. We have mostly considered philanthropy to fit where markets or government fail, but the scaling continua now positions philanthropy as a starting point that ultimately leads to either market or government adoption. Ironically, for all the talk of hybrid models, this picture shows philanthropy and impact investing not as a blended option, but simply as two paths to scale.

Policy implications

The intertwined paths of impact investing and philanthropy have created a regulatory mosh pit, where rules of different domains are overlaid confusingly atop one another, jostling for position. The capital itself may be laid out on a spectrum, but the governance mechanisms for public accountability, the different transparency and reporting standards, and the definition of fiduciary responsibility for philanthropists and investors don’t align so much as stand in stark contrast to one another.

Several possibilities arise. Perhaps we will see more hybridization of the investor form, not just the enterprise form. We likely will continue to see innovation in financial products, perhaps even new ways to share the costs of due diligence or to value that diligence as a shared public good. Given the array of enterprises and capital working on social problems, we may come to incentivize social outcomes in an “organizationally or sector agnostic” way, focusing more on what is accomplished and less on the type of organization that accomplishes it.

One participant in the group noted that we are in a moment of learning to “toggle” along many continua at once—capital, impact, transparency, and timing. However, it seems less likely that we can continue to “toggle” back and forth across the regulatory lines that lie between these practices. We may soon need to redraw the boundaries.

All materials from and information about the project can be found at ReCoding Good and through the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society’s Digital Civil Society Lab. We invite you to subscribe to our email list, talk with us on Twitter (#ReCodeGood), and join us in person whenever you can.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Lucy Bernholz, Rob Reich & Chiara Cordelli.