Oakland, Calif., was the last stop on our 16-day North American tour. In a stark basement office, three blocks from the train station, we heard a different answer to our question, “Where do good ideas for solving social problems come from?” By the time we arrived in Oakland, weʼd posed that same question to foundations, social venture funds, social innovation hubs, academic centers, government units, and community groups in Austin, Chicago, Toronto, Montreal, Boston, New York City, and San Francisco. Working for the last year in Australia, and for four years before that in the UK, weʼre interested in where and how ideas emerge in different contexts, and when and how promising solutions scale.

Solutions, most people told us, came from entrepreneurs and experts. Ideas for those solutions came from…well, no one could really tell us.

That was until we met Maurice Miller and Mia Birdsong, founders of the Family Independence Initiative (FII), late in the afternoon of our final day in the US. They were adamant about where ideas didnʼt come from.

“In America, we have had a 47-year war on poverty. Everybody knows we have not impacted poverty. It is actually totally logical to go to families and say, after 47 years of the smartest people with a lot of money and resources trying it their way, it’s your turn,” Miller said.

FII gives working poor families the resources to find and implement ideas that get them out of poverty. For FII, the best ideas come from people who are experiencing social challenges themselves. FII learns from and pays families, rather than researchers or consultants. By collecting data directly from families about what works (and when and where), they hope to influence how welfare systems operate. Solutions are the product of ideas developed and tested by families.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Like FII, we think itʼs critical to invest in bottom-up ideas and solutions.

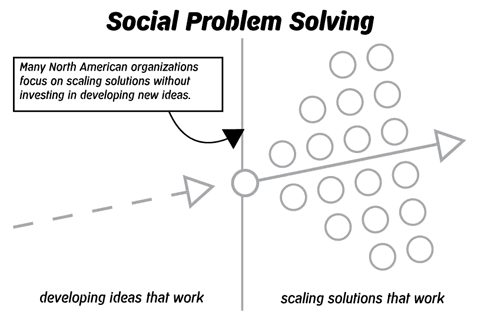

What we saw in most of the organizations we came across, such as Root Cause, New Profit, and the ASH Center for Democratic Governance, were sophisticated methodologies for selecting and scaling solutions—far more sophisticated than those we encountered in the UK or Australia.

What we didnʼt see was the same level of sophistication or rigor in developing and testing ideas.

The big social challenges of our time—problems like educational disengagement and chronic health disease—are defined by their complexity. They have multiple, interlocking causes that render any one solution or theory of change incomplete.

That means that solving the big social challenges of our time requires change at multiple, interlocking levels: at a system, community, family, peer, and ultimately, individual level. At the end of the day, unless children participate in learning, or people eat and exercise differently, educational disengagement and obesity will remain so-called intractable problems.

Enabling people to shift their behavior works better when they see the value of such change and take ownership over the change process. In other words, itʼs much easier when people are the source of ideas for what should change, and when and how that change happens, provided we are also able to remove barriers at the broader system and community levels.

We use the word co-design to describe an approach of working with people to develop and prototype the ideas that will enable them to live the lives they want. We use the word coproduction to describe solutions that tap into peopleʼs natural resources—their skills, experiences, time, and money—to enable different outcomes. Ideas may take the form of new roles, interactions, materials, services, and policies. Solutions may take the form of new networks, platforms, organizations, or movements. In our work at The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (TACSI), we’ve spent the last 12 months co-designing ideas with families. Now, weʼre working with families to spread and scale a new network of families helping families, and beginning a new project with older caregivers and those they care for to develop and test ideas for improving relationships and outcomes.

A handful of institutions outside of North America are investing in co-design—ironically without investing in the sophisticated mechanisms we saw in North America for scaling the solutions that co-design may yield.

Back home in Australia we met with Lynelle Briggs in her fourth-floor, corner office that overlooks Canberra’s still lakes and rolling hills. After a long career as a public servant, Lynelle was about to retire as chief executive of Medicare Australia. There, she helped to establish the countryʼs first co-design unit inside the biggest government department: the Department of Human Services.

She explained, “The journey of moving towards co-design was one of being frustrated with what we had and thinking we needed something better. Co-design means that people in the community have the opportunity to engage with us in the thinking about policies, the design and choice of what policies are most suited to them, and the design of the services as they are delivered, and give us feedback after they have got them.” For Lynelle, co-design isnʼt just a fancy word for consultation; it’s a concept that requires re-sequencing how services are designed and delivered.

Government investing in processes, rather than just solutions, was deemed near heresy in the US. Even progressive city departments on the West and East coasts expressed deep skepticism that government could play a constructive role. The assumption was that government—at any level—was too risk-averse and bureaucratic to generate ideas by working directly with people. Michele Jolin underscored that view in her Summer 2011 Stanford Social Innovation Review article “Social Innovation in Washington, D.C.”: “Although government lacks the flexibility and tolerance for risk that are critical to innovation, government investments can be structured to fund evaluation and support scale, both of which are critical in later stages of the innovation cycle.”

Australia provides an instructive counterexample. Government investments can be structured to support bottom-up idea generation. What the co-design unit can do from inside the federal government and what TACSI can do outside of state government is demonstrate that starting with people—not just with entrepreneurs or experts—produces better results.

It took over ten years for FII to gain national attention and convince major funders that working with families, from the ground-up, produces better results. Experts and entrepreneurs were no match for families themselves. We hope it takes far less time to convince social innovation organizations in North America to invest in where ideas come from, and to convince social innovation organizations in Australia to invest in scaling solutions that work.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Chris Vanstone & Sarah Schulman.