“They’re telling you questions, Asking me lies”—The Replacements

“Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, has always been the systematic organization of hatreds.”—Henry Adams

With the most punishing economy since the Great Depression, and severe budget challenges at the federal level and in 48 states, now is a critical time for nonprofits seeking to protect the vulnerable and to promote a fairer, more just society to win people to their cause. Unfortunately, appeals to caring for the needy or increasing fairness are likely to backfire unless advocates are careful to acknowledge and avoid inflaming passions that stem from other powerful moral values.

Our attitudes on issues and situations are affected instantaneously by intuition and emotion, as Drew Weston in The Political Brain, Malcom Gladwell in Blink, and others have taught us. There is tremendous potential power in understanding such “intuitive primacy.” Indeed, putting our pre-rational selves to work may be the key to effective change, as Chip Heath and Dan Heath convincingly argue in their book Switch: How to Change When Change is Hard. In Switch, they make the point that big changes can start with very small steps, provided that we can align people’s aspirations—speak to their emotions—and help direct them with simple, clear directions. Their framework for change is built on research from moral psychology and is framed around a metaphor posed by Jonathan Haidt, a professor at the University of Virginia. Haidt illustrates the primacy of intuition by describing our rational minds as a rider sitting astride an elephant. The rider may be able to control the elephant with reason for a brief while, but eventually the rider gets tired or paralyzed by too much analysis, and the elephant in the end is only going to move when it is ready, toward what its gut wants. The Heaths provide a persuasive theory of change: 1) Direct the Rider, 2) Motivate the Elephant, and 3) Shape the Path (set up the environment to make doing the right thing easier). Switch is a fantastic, inspiring book and should be read by anyone concerned with changing communities and organizations for the better.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

The primacy of intuition and emotion can be so strong that it determines what people see as a fact. A recent article by Chris Mooney, “Rapture Ready: The Science of Self-Delusion,” provides an excellent overview of moral psychology. Mooney concludes: “You don’t lead with the facts in order to convince. You lead with the values—so as to give the facts a fighting chance.” (emphasis added).

But which values? And how do you speak to people who hold values different from than the ones you are trying to advance?

Jonathan Haidt’s research into moral foundations can help direct our riders here. Research shows that while people are nearly incapable of seeking out evidence that might contradict their beliefs, they are wizards at finding evidence to justify their beliefs and actions. Haidt emphasizes that we use our reasoning powers primarily to justify decisions that appeal to us for emotional and gut reasons—“moral reasoning is for social doing”—and therefore cautions that it is nearly impossible to use reasoning to persuade people to believe something they don’t want to believe.

Further, since our social evolution has grown out of competition among tribes, Haidt postulates that the power of religion and morality may be viewed as an adaptation for binding large groups together: “Morality binds people together and then blinds them to arguments and appeals from outside of their group.”

In his forthcoming book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, Haidt describes five moral foundations, based on years of research he and his colleagues have conducted into the moral preferences of over 126,000 people across multiple countries. These are:

• Care/Harm: evolved from the human need to care for vulnerable children with longer development spans than other mammals.

• Fairness/Cheating: evolved from the challenge of reaping the benefits of cooperation without being exploited.

• Ingroup Loyalty/Betrayal: Stemming from the challenge of forming and sustaining coalitions, this foundation leads us to trust and reward “team players” and to punish, ostracize, or kill those who betray the group.

• Authority/Subversion: grew from the challenge of creating mutually beneficial relationships within hierarchies—necessary as cultures and societies became more complex.

• Purity/Degradation: enables people to attach sanctity to objects, like the human body, beyond what is merely rational. This is also thought to have come from the challenge of living in a world of pathogens and parasites, evolving into part of the “behavioral immune system,” and binding people across different tribal groups through shared beliefs about the sacred and profane.

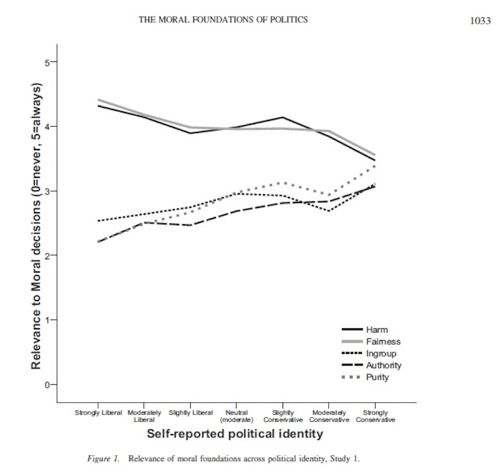

Haidt’s research indicates that people at the liberal end of the spectrum value Care and Fairness much more than Loyalty, Authority, and Purity, while people in the middle and at the conservative end of the spectrum respond more to appeals to all five moral foundations, as shown in the table below (from a 2009 paper “Liberals and Conservatives Rely on Different Sets of Moral Foundations”).

Haidt emphasizes that this dynamic exists across many very different countries and cultures.

In The Righteous Mind, Haidt observes that these dynamics give conservatives an advantage in the political and cultural sphere—they speak to all five moral foundations, while liberals primarily appeal to care and fairness as freedom from domination.

It can be tempting to discount opposition to appeals for social and economic justice as motivated by ignorance, fear, or even bad faith. Haidt cautions all of us instead to first assess whether opposition might be motivated by sincerely held but different moral beliefs, and to be humbler about our own values when trying to persuade others.

In my experience, the secular nonprofit sector is dominated by people who prioritize the Care/Harm and Fairness foundations much more than Loyalty, Authority, and Purity. Nonprofit leaders already rely too much on appeals to reason, but even when we do speak to people’s emotions, we would do well to follow Haidt’s advice:

• Approach each issue by running through all five moral foundations.

• Don’t expect good factual arguments to change any minds on their own.

• Prepare the emotional ground first; try to trigger positive intuitions before stating a point likely to trigger positive emotions.

The next time I am working on a Care or Fairness issue, for example, I hope I remember to try to enlist another foundation, too, such as Loyalty (e.g., “These are our people, our friends, and neighbors…”).

I’m sure I have not come close to doing justice to Haidt’s research or the field of moral psychology as a whole, but I think there is great promise in this and hope to learn more. To explore your own moral views and where you may fit in the spectrum, visit YourMorals.org and watch Haidt’s compelling 2008 TED talk.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Peter Manzo.