An IDinsight surveyor administers the ASER assessment to measure learning outcomes in Mandalgarh, Rajasthan. (Photo by Ryan Fauber)

An IDinsight surveyor administers the ASER assessment to measure learning outcomes in Mandalgarh, Rajasthan. (Photo by Ryan Fauber)

Over the past year, development impact bonds, or DIBs—international development’s newest hot trend—have generated a tremendous amount of buzz from champions and detractors alike, along with some serious money. The latest flurry of activity includes an $11 million education impact bond in India, the first development impact bond in Africa, several ambitious outcomes funds (including two aiming to raise $1 billion each), and a recent global convening full of heavy hitters. While all these efforts aim to advance the idea of tying payments to real improvements in people’s lives, they also exhibit tremendous variation—and perhaps some confusion—on what it actually means to pay for “impact.”

As this nascent field rapidly develops, there is an urgent need to develop a set of shared standards around what impact means, how to measure it, and how to tie it to payments. With billions of dollars poised to flow into these instruments, the consequences of getting it wrong are massive. On one side, we have the potential to incentivize service providers to solve hard problems by ensuring that capital flows toward programs that improve lives. On the other side, we risk wasting considerable time and money on complex financial instruments that could perversely incentivize implementers and donors away from the most impactful activities. As a sector, we need to stay focused on the main prize: putting money behind programs that we are confident improve lives.

As a sector, we need to stay focused on the main prize: putting money behind programs that we are confident improve lives.

At IDinsight, we first tackled these issues directly in our evaluation for the Educate Girls DIB, the world’s first completed DIB, which aimed to improve education outcomes for marginalized students in rural Rajasthan, India. We are also currently evaluating Africa’s first DIB, the Village Enterprise DIB, which aims to create more than 4,000 sustainable microenterprises to benefit poor households in rural Kenya and Uganda. And we are advising on a wide range of other impact bonds and outcome funds. Based on these experiences, we have developed some core principles for measurement on future impact bonds, with the goal of maximizing the chance that this instrument delivers on its promise to improve lives. Here’s a look at four things evaluations for impact bonds must do.

1. Measure What Matters

Proponents of impact bonds laud their “laser focus” on outcomes. As when firing a laser, however, you need to have the right target in sight first. This is important, because impact bonds create high-pressure incentives to perform by setting impact targets in advance and tying success to payments. Chosen carefully, these incentives can help implementers become more effective at improving lives. Choosing the wrong outcomes, however, can force implementers into lose-lose decisions between meeting targets and helping people.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

All impact bonds should be based on outcomes that: 1) capture real improvements in people’s lives, 2) can be measured, and 3) hold up under pressure.

Choosing outcomes that matter means thinking hard about what success would actually look like for a given program. For an education intervention, success often means increased learning. For a health intervention, it might mean decreases in death rates or disease. While the right outcome can and should vary by context, it should also reflect real improvements in peoples’ lives. Measuring inputs instead of outcomes locks implementers into a particular way of doing things, which may not lead to the impact you actually want.

Consider Educate Girls, which seeks to improve educational outcomes through volunteer-based remedial instruction. Tracking whether the program delivered specific inputs—such as recruiting a certain number of volunteers or conducting a certain number of classroom sessions—would have stymied its ability to figure out what rural government schools in Rajasthan really needed. But because the DIB payments were primarily tied to learning gains, not specific activities, Educate Girls could be ruthless about making major changes to parts of the program that were not working. When results at the end of the first year showed growth below targets, it rolled out a completely new curriculum in the second year; when growth was still lagging, it added at-home remedial instruction as a core responsibility of volunteers. If targets had been tied to particular activities instead, Educate Girls would have been held back from making these bold and necessary pivots.

While an impact bond’s outcomes should signal meaningful impact, they also need to be measurable. Having “fuzzy” or unreliable measures undermines incentives, invites lengthy renegotiation, and can leave impact bond participants feeling like they are not being adequately credited for successes or failures. Some things are just harder to define and measure—for example, “Is this child resilient?” is more difficult to measure than “Can this child read a sentence in Hindi?” When considering possible outcome measures, it is best if you can observe the outcome directly and identify any clear definitions of success already in use. An impact bond for a public health intervention to instruct teenagers in safer sex practices probably should not tie payments to notoriously unreliable self-reports of contraception usage. But you might be able to set targets for a reduction in teen pregnancies.

Outcome metrics must also be difficult to manipulate. Impact bonds don’t just nudge participants toward targets—they hold everyone’s feet to the fire! You should expect implementers to take the chosen outcomes seriously, even literally. This means that relatively fragile measures, such as self-reported tests of “grit” (resilience), may not hold up under pressure. If everyone knows that the ultimate success or failure of the program will be judged by a child’s self-reports of certain skills, there will be incredible pressure to coach children to give the “right” answer without necessarily building the underlying skills the question is trying to capture. Even proponents of these tools often agree that programs should not use them in high-stakes environments. For example, Angela Duckworth, who developed the “grit” scale, pushed back on plans to include it in certain assessments in California.

2. Give Credit Where Credit’s Due

The core value proposition of DIBs—payment for results—depends on our ability to accurately measure a program’s success. Any evaluation for an impact bond must convincingly measure the impact of the program over and above any changes that would have happened anyway. If the evaluation fails to do this, the potential benefits of DIBs collapse. The implementer’s incentives for good performance will be missing or distorted; the outcome payer cannot be confident they are paying for results; and the investors will not know if they will be fairly compensated for a successful program.

There are many examples of why this is so important to get right. In a previous evaluation of Educate Girls’ program, researchers found that enrollment actually fell in program schools. However, data from nearby schools showed that enrollment was falling even more dramatically across the district. Educate Girls’ program was actually quite successful in slowing an exodus caused by outside forces. But an impact bond based on simple enrollment counts in program schools would have unfairly led to negative returns for investors and wrongly showed Educate Girls was having a negative impact, when in fact the opposite was true.

Overestimating impact can also lead to trouble. For example, a 2015 Goldman Sachs-funded social impact bond in Utah sparked controversy amid claims that the evaluation overstated the number of children the program helped, since it lacked a credible comparison group. Those doubts—paired with the fact that Goldman Sachs made a tidy profit off a program intended to help preschoolers avoid the need for special education—can play into existing concerns that impact bonds prioritize investment opportunities over social impact.

Does measuring impact always mean running a randomized controlled trial (RCT)? Not necessarily. But it always requires some kind of credible comparison so that we can compare what did happen under the program to what would have happened without it. Academic literature provides hundreds of examples of how to reliably measure the impact of social programs. The exact approach for a particular impact bond should follow from the outcomes it is measuring, as well as program implementation and budgetary constraints.

When feasible, RCTs are a great way to capture ironclad estimates of program impact. But there are also a range of quasi-experimental designs that seek to mimic randomization and can work in certain circumstances. (For instance, IDinsight regularly employs matching studies, in which a control group is carefully constructed to match the treatment group based on certain observable characteristics.). Of course, the devil is in the details, and organizations must take care to check that the evaluation, whether it’s an RCT or uses a different methodology, is appropriately designed. We recommend that evaluation designs for impact bonds undergo an external review by a qualified expert. We are not suggesting an extremely lengthy or costly review process, but rather a quick check on the major design decisions and assumptions by a methodological expert so that donors can be confident they are paying for actual impact.

While the evaluation design should fit the specific circumstances of the impact bond, we generally caution against the widespread use of before-and-after designs given the complex and dynamic environment in which most programs operate. Without a comparison group standing in for business-as-usual changes, it is impossible to know which changes resulted from the program and which resulted from outside forces. As we saw in the examples from Educate Girls and the Goldman Sachs impact bond, this is not just about getting results that are slightly off; the approach can lead to entirely wrong conclusions about whether a program worked or not, thereby undermining the entire purpose of impact bonds “paying for results.”

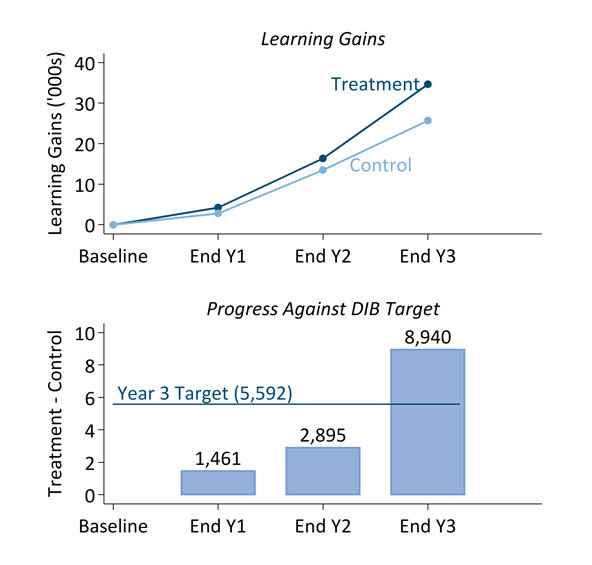

Top panel: Students in treatment schools outstripped students in control schools over the course of the evaluation, particularly in the final year. Bottom panel: Due to strong performance in the final year, Educate Girls exceeded DIB learning targets by 60 percent.

Top panel: Students in treatment schools outstripped students in control schools over the course of the evaluation, particularly in the final year. Bottom panel: Due to strong performance in the final year, Educate Girls exceeded DIB learning targets by 60 percent.

3. Facilitate Innovation

So far, the global conversation around measurement in impact bonds has mostly focused on how they build accountability. But the Educate Girls DIB reveals that impact bonds’ hidden superpower may be encouraging rapid learning and improvements. Participating in an impact bond can directly motivate program changes by pairing clear targets with insights into what is and is not working.

In the first two years of the Educate Girls DIB, the program fell short of targets. While internal assessments showed steady growth, the evaluation data revealed that growth was limited to children who were regularly attending school. Meanwhile, children who were chronically absent—and missing from Educate Girls’ data—lagged far behind. With just one year left in the program, it looked unlikely that the program could meet learning targets. However, the flexibility of the DIB allowed Educate Girls to identify the missed potential in chronically absent students and make big course corrections, including adding visits from volunteers to students' homes for remedial tutoring to the program. The result? By the end of year three, these students had nearly caught up to their peers, leading Educate Girls to exceed learning targets by 60 percent in its final year. If the DIB had relied on only validated data from the implementer’s internal assessments—as many impact bond evaluations do—we would have never identified this issue with chronically absent students, Educate Girls would not have added home visits, and many children would been left behind.

Impact bond designers must thoughtfully weigh trade-offs between different approaches to measurement to get the most bang for their buck.

In other words, it’s worth investing in a rigorous evaluation! Bad evaluation undermines the effectiveness of the program—and ultimately the impact bond—by giving stakeholders misleading information about progress. Implementers and investors deserve the chance to assess what is and is not working, and to make course corrections along the way.

You can also create opportunities for learning by collecting additional data in a targeted way. In the Educate Girls DIB, the bulk of the payments were based on results from the final year of the evaluation. A leaner evaluation therefore might have assessed students only in the last year. But through frequent assessment, we were able to help the implementer track progress toward targets, identify areas for improvement, and check its internal assessments against IDinsight’s data. Similarly, collecting data beyond learning scores—such as gender, caste, and absenteeism—enabled us to identify who the program was benefiting and who it was leaving behind so that Educate Girls could make targeted adjustments.

4. Right-size the Evaluation

Critics often knock impact bonds for their complexity and cost, and they have a point. For impact bonds to deliver on their promise, they have to find a balance between quality and efficiency. However, this should not mean indiscriminate cost-cutting. Instead, impact bond designers must thoughtfully weigh trade-offs between different approaches to measurement to get the most bang for their buck.

Fortunately, most evaluations involve fixed costs that do not scale with the size of the program. An education program 10 times the size of the Educate Girls DIB would, under most conditions, cost roughly the same amount to evaluate. As impact bonds get larger, the relative cost of evaluation will decrease.

Case in point: Our evaluation of the Village Enterprise DIB is a fifth of the cost of the Educate Girls DIB evaluation as a percentage of the overall cost of the DIB, despite higher transportation and labor costs in East Africa compared to India. We were able to achieve a much lower evaluation-to-overall-budget ratio through two main mechanisms. First, the Village Enterprise DIB is much larger ($5.26 million total budget, versus less than $1 million for the Educate Girls DIB). Second, we kept the core elements for a rigorous evaluation while being extremely discriminate in adding activities that were not absolutely necessary for estimating impact on the DIB metrics. For instance, rather than include all participating households in the evaluation, we randomly selected a representative sample of 12 percent of eligible households that would generate sufficiently precise estimates for the outcome payer. We eliminated baseline data collection since it was not strictly necessary for estimating impact; by randomly assigning a large sample of villages to treatment vs. control groups, we could be sufficiently confident that the treatment and control groups would be statistically equivalent on average, and any differences at the end could be attributed to the program. We reduced data collection costs by training enumerators to use digital data collection tools, which avoided the need for costly data entry and redundant quality checks. Finally, where possible we relied on existing administrative data, such as Village Enterprises' data on transfer receipts, and conducted targeted spot checks to validate that data, rather than re-collect the same indicators.

Of course, there are tradeoffs between evaluation cost and the richness of evidence that implementers can use to enhance their effectiveness. Therefore, impact bonds should balance concerns around cost with the value of other information the evaluation could generate. These competing goals for evaluation have implications for who should bear the evaluation costs. In most impact bonds, the outcome payer, who has the most direct incentive to ensure an accurate accounting of the program’s success, pays for evaluation. However, the implementer or investor could consider paying for intermediate data collection to inform course corrections and increase the chances of meeting targets.

Getting DIB Measurement Right

Are impact bonds the right tool in all situations? Unfortunately, no. Do impact bonds take a lot of work? At the moment, yes. There are plenty of smart people at organizations like Instiglio, Social Finance, and Brookings working hard to make them simpler and decrease transaction costs, but they will likely always be more complex than traditional grants.

At the same time, we are cautiously optimistic about many of the claims made in favor of impact bonds. If we can get the measurement piece right, we believe they have the potential to fundamentally shift the development sector’s focus from inputs to outcomes, and to bring new funding and solutions to challenging social problems. We have also seen firsthand how impact bonds can act as a laboratory for innovation.

Meanwhile, billions of dollars are already flowing to this new, largely untested tool. That is all the more reason to make sure these complex structures are grounded in sensible approaches to measuring impact. In 10 years, we want to be sure impact bonds are saving lives and reducing poverty—not a cautionary tale of another failed development fad. For that positive story to materialize, we need to build on what we already know about what impact means and how to measure it well.

Correction: November 22, 2018 | The Village Enterprise development impact bond has a $5.26 million budget, not $10 million.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kate Sturla, Neil Buddy Shah & Jeff McManus.