In more than a decade of research on nonprofit leadership, we at The Bridgespan Group have observed little change in the No. 1 organizational concern expressed by boards and CEOs: succession planning. In survey after survey of nonprofit leaders succession planning comes out on top. In fact, it is mentioned twice as often as the next concern.1 Our most recent research provides a clue as to why. Only 30 percent of C-suite roles in the nonprofit sector were filled by internal promotion in the past two years—about half the rate of for-profits.2 Even more concerning, this low promotion rate did not vary by the size of the organization: larger organizations, which should have more opportunities to promote internal talent, are not doing so.

Despite the many articles and numerous discussions about the need for organizations to develop their human capital, too many nonprofit CEOs and their boards continue to miss the answer to succession planning sitting right under their noses—the homegrown leader. Our new study surfaced what we call a leadership development deficit. The sector’s C-suite leaders, frustrated at the lack of opportunities and mentoring, are not staying around long enough to move up. Even CEOs are exiting because their boards aren’t supporting them and helping them to grow. This syndrome is coming at a significant financial and productivity cost to organizations, undermining their effectiveness and hampering their ability to address social and economic inequities. “In the for-profit sector, I saw organizations saying ‘a known is better than an unknown’ and work to promote from within,” says Amy Smith, chief strategy officer and president of Action Networks, at Points of Light. "I see nonprofit organizations looking outside first for talent instead of exploring the expertise they already have in house." This syndrome won’t change unless boards, management teams, and funders change their ways.

Turnover Treadmill

In our 2006 study, The Nonprofit Sector’s Leadership Deficit, Bridgespan predicted that there would be a huge need for top-notch nonprofit leaders, driven by the growth of the nonprofit sector and the looming retirement of baby boomers from leadership posts.3 In 2015 we tested those predictions by surveying 438 nonprofit C-suite executives, interviewing dozens of senior and emerging leaders,4 and analyzing 20 related outside studies. We found that our predictions were pretty much on the mark—the need for C-suite leaders5 grew dramatically. But we also found, happily, that supply grew with it. Organizations largely found leaders to fill the demand.

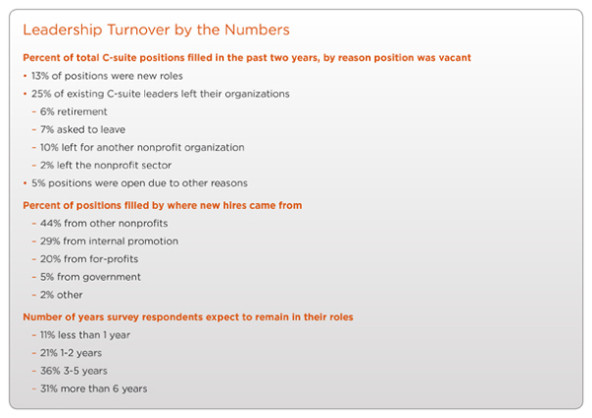

Crisis averted? Unfortunately not, because those jobs keep coming open. Our research finds that demand for effective nonprofit leaders today is as high as ever. Survey respondents had to fill 43 percent of C-suite roles in the past two years. Some of this was due to growth—13 percent of these positions were new in the past two years. Much of it, however, was because senior staff left the organization. In the past two years, one in four C-suite leaders left her position, and nearly as many told us that they planned to do so in the next two years. If these projections turn out to be true, the nonprofit sector will need to replace the equivalent of every C-suite position over the next eight years.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Why the recurring exodus? Surprisingly, little is due to the wave of retirement we have all been expecting: only 6 percent of leaders actually retired in the past two years.6 Instead, the major reason is turnover: 12 percent of all nonprofit leaders left their jobs to go to other organizations, and another 7 percent were asked to leave. When asked about future plans, one third of respondents said that they intend to leave in the next two years. Meanwhile, the largest source of replacement talent came from other nonprofits, exacerbating a turnover treadmill at a time when the sector needs experienced, capable leaders more than ever. (See “Leadership Turnover by the Numbers.”)

True Costs and Root Causes

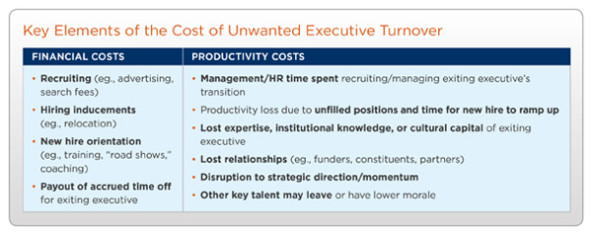

Some level of turnover at an organization is inevitable—in fact, it can be healthy—and all organizations need to have recruiting and onboarding practices in place to deal with it. Undesired turnover, however, whether voluntary or involuntary, can exact a significant price to the organization. The transaction costs alone of finding and attracting a new employee, particularly at the senior level, can be as high as half of her annual salary. But the costs to an organization in productivity, fundraising, and distraction (as members of the board and senior team turn to recruiting and onboarding critical staff positions), can add up to tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars more.7 (See “The Costs of Unwanted Executive Turnover.”)

One study suggests that losing a star performer in a senior development role costs nine times her annual salary to replace.8 Then there are the effects on program outcomes. Another study found that student achievement is lower the year after a principal leaves the school, and that it takes an average of five years for new principals to have a positive impact on student outcomes.9 For-profit research suggests that the time it takes for an external hire to become productive is twice as long as for someone hired from within;10 that the true costs of onboarding an external hire are up to twice the departing executive’s salary; and that as many as 40 percent of externally hired executives fail within the first 18 months.11

The Costs of Unwanted Executive Turnover

Given these high costs in dollars, productivity, and effectiveness, nonprofits should have enormous incentive to attack the root causes of turnover. Not surprisingly, the majority of our survey respondents (57 percent) attributed their retention challenges at least partially to low compensation, an issue that can feel daunting to many nonprofits. Lack of development and growth opportunities ranked next, cited by half of respondents as a reason that leaders leave their organizations. Fortunately, this is a problem that nonprofits can address cost effectively, regardless of size, by developing emerging leaders already on the payroll.

This data highlights an alarming and broader challenge for the nonprofit sector. Ultimately, an organization that fails to develop its people will find it more difficult to effectively achieve its goals. This is something many for-profit organizations understand well and invest accordingly. Indeed, corporate CEOs dedicate 30 to 50 percent of their time and focus on cultivating talent within their organizations.12 Nonprofit CEOs who don’t follow suit are missing a key lever for boosting their impact.

When we asked respondents what was missing in their development, two themes emerged. The first was a lack of learning and growth. We repeatedly heard that leaders feel compelled to leave their organizations to move to the next level. The data that we cited at the outset—only 30 percent of senior roles in the sector were filled by internal promotion in the past two years—confirmed this. Aside from getting promoted, many people that we interviewed wanted to expand their skills and broaden their experience within their roles. “I haven’t even had the right experiences to move to the next level if I wanted to,” says a C-suite executive at a Jewish federation. “I need to learn to manage people and to build my external networks.”

The second reason people left was because of a lack of mentorship and support. Other respondents told us they lacked an internal champion to support their career growth and inquire as to their job satisfaction. We heard this from all stages of the leadership pipeline, including CEOs, who said that their boss, the board, failed to mentor them or, worse, made life more difficult by micromanaging. “My plans to stay or leave change relatively frequently,” says the executive director of a youth development organization in Pennsylvania, “and relationships with the board are the primary factor.” She went on to describe the difficult experience of working with a very directive board chair who treated her more like executor than executive. This is a common story: In a recent poll conducted by the research organization Waldron, the number one reason CEOs say they would leave their current role, other than to retire, was difficulty with the board of directors.13

Some organizations systematically develop and support promising leaders, but too few. In our survey, more than half of respondents ranked their organizations lower than 6 out of 10 on their ability to develop their staff. When asked why, respondents said that their organizations lacked the talent management processes required to develop staff, and that they had not made staff development a high priority. Only 16 percent felt that their organizations actually lacked the capability to offer appropriate training and experience, a surprisingly low percentage given that external training is the solution to leadership development that many default to.

Indeed, a major cause of leadership turnover—nonprofits’ failure to cultivate homegrown talent, which drives senior staff to leave for growth opportunities elsewhere—appears addressable. But our research and experience indicate that the solution requires the skill and will on the part of senior leaders, boards, and funders to build processes for leadership development within organizations.

Reversing the Trend

To understand what it takes to effectively support and develop leaders, it’s useful to explore exactly how adults learn. Studies in the academic and corporate world14 find the most indelible lessons stem from a combination of learning through doing, learning through hearing or being coached, and learning through formal training. The Center for Creative Leadership has helped corporations like American Express get this combination right, championing an approach called the 70/20/10 Model for Learning and Development, which asserts that adults learn approximately 70 percent through on-the-job stretch opportunities, 20 percent through coaching and mentoring, and 10 percent through training programs to grow discreet skills.15

The majority of this learning takes place within the organization—through the practices and behaviors of its leaders. It doesn’t require a raft of expensive external trainings or programs, although it does require time and dedication to building a talent development system. One way to think about 70/20/10 is as the do-it-yourself approach to leadership development.16

Cesar Bocanegra, the COO of education crowdfunder DonorsChoose.org, which finances classroom-based projects, attributes the low turnover of its senior leaders to the leadership development approach of CEO Charles Best. “He is an amazing leader and excellent manager,” says Bocanegra. Best has used DonorsChoose.org’s growth—from 25 employees when Bocanegra started in 2007 to 75 today—to expand executives’ aegis. “I began as VP for operations,” says Bocanegra, “then, two years later I became COO and added oversight of human resources.” He adds that the culture of continuous improvement means everyone is looking for the next way to stretch her skills and processes. Individuals assign themselves stretch goals—and they often need mentoring to attain them.

Bocanegra cites the story of a colleague who took on the challenge of deepening outreach to teachers. She came up with a novel idea: giving teachers a promo code that they could share with friends and family. Her idea was that anytime the friends or family used the code to make a donation, DonorsChoose.org would match it, effectively turning teachers into fundraisers. Of course it also meant DonorsChoose.org would be on the hook to produce matching funds. But senior management encouraged her creativity and coached her on the “how.” Over the course of a year, with mentoring and peer collaboration, they worked the kinks out, offering the code for a limited time only —seven days—and finding corporations willing to sponsor it with their logos. That promo code is now the leading driver of new donors to DonorsChoose.org, and its creator developed new skills in fundraising and community building in implementing it.

With 70/20/10 leadership development embedded in its culture, DonorsChoose.org has not had a single member of its seven-person executive team leave the organization in eight years, enabling them to gel as a team and lead the organization to greater levels of impact.

Allowing people to stretch and grow isn’t just about getting promoted. It’s also about building new skills and experiences at all points in a career. “We have an association conference every year,” says Chuck Wingate, executive director of Bethesda Mission, Harrisburg, Pa. “I send a younger person to represent our organization [in order] to send the message that we are committed to that person’s future at our organization. They are almost always the youngest person at that conference—why aren’t other organizations giving similar opportunities to their staff?” This is particularly important in smaller organizations where there are simply fewer rungs on the career ladder to move upward.

One of the most common obstacles to effective leadership development cited by interviewees was the size of their organization. Small and typically flatter organizations provide fewer opportunities for promotions, even for the most promising staff. However, our research shows that skill development can compensate for lack of upward trajectory. Stretch opportunities abound in smaller organizations where a large number of responsibilities are divided among a small number of people. This can feel like staff members are being thrown in the deep end. But with support and coaching, the deep end can offer exciting challenges that grow skills. Building the most effective leaders possible is particularly critical for smaller organizations, where any weak link can weaken the entire chain.

Some leaders fear that their leadership development investments will walk out the door. Recent for-profit research, however, suggests just the opposite. CEB, a provider of corporate best practices research and analysis, found that staff members who feel their organizations are supporting their growth stay longer than those who don’t, because they trust that their organizations will continue to invest in them over time.17 Emerging leaders still may ultimately leave the organization to progress in their careers, but if an organization is able to delay that exit by months or years by offering greater development opportunities, they’ll reap the benefits in the meantime. Adam Simon, director of leadership initiatives at the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation, highlights the virtuous cycle: “When you invest in developing talent, people are better at their jobs, people stay with their employers longer, and others will consider working for these organizations in the first place because they see growth potential.”

Connecting Talent Development to Organizational Goals

In Bridgespan’s 2012 book, Nonprofit Leadership Development: What’s Your ‘Plan A’ for Growing Future Leaders? based on collaborative research with 30 nonprofits committed to leadership development, we identified four elements organizations should have in place to align their strategy for talent to their goals for impact.18

- Managers who are committed and effective talent champions with accountability to mentor and develop others.

- Identification of development opportunities aligned to organizational goals and individual needs, and differentially allocated to the most promising rising stars.

- Co-created individual development plans that help staff members identify what skills they need to develop to push the organization toward its goals, what development opportunities they should take advantage of, who their mentors will be, and where supplemental formal training will be valuable.

- Mechanisms to ensure follow-through on development plans, including linkages to performance reviews rooted in strategic objectives.

Sister Paulette LoMonaco, executive director of Good Shepherd Services in New York City has invested significant senior executive time in order to link everyday work to leadership development that ties directly to the future needs of her organization. “First, we looked at our future leadership needs, then defined future skills and capacities to meet those needs, and embedded those skills into the criteria by which we assess our top leaders in the organization,” says LoMonaco. “From there, our executive team created development goals for their respective direct reports.”

LoMonaco and her senior team identified development experiences and assignments to help 50 emerging leaders meet leadership development goals. They also identified the mentoring and formal training needed to help individuals to move up in responsibility. Good Shepherd’s CFO Greghan Fischer, for example, saw strong potential in a quietly competent member of her finance team named Yan Li. Fischer created the following development goals and accompanying 70/20/10 assignments for her:

- Strengthen communications during meetings: CFO to provide mentoring and an outside coach.

- Guide more senior program directors on budgetary and strategic questions. CFO will provide stretch opportunities to lead budget meetings.

- Provide big picture context for financial goals. CFO will coach on situating fiscal objectives within the broader GSS strategy.

Fischer began with mentoring, personally coaching Li and giving her practice in leading budget meetings. At each meeting she observed Li’s leadership style and afterward provided feedback. To help Li overcome her natural reticence, Fischer brought in a communications coach. Li’s stretch assignment began when Fischer took maternity leave: Li took charge of all budget meetings, which forced her to translate her analytical skills into clear recommendations. “She stepped in and led budget meetings and did it so well that people felt clarity and support,” says LoMonaco. “And Li pushed others to grow in their analytics; she is teaching and directing more senior program directors. The transformation is striking.” On Fischer’s return, she promoted Li to assistant director of contracts. “She will now stretch us all to think of things a little differently, role modeling for others that they can grow in confidence and position, too,” says LoMonaco. “She literally has found her voice.”

Getting Started

For organizations keen to advance their missions, and avoid succession setbacks, growing leaders from within is a smart start. But doing so takes focus, resources, and action on the part of nonprofit executives, their boards, and their funders.

For starters, nonprofit executives need to uncover and attack the root causes of turnover, broadening their focus from recruiting new leaders to fill recurring gaps, to prioritizing growing and retaining the talent that they already have. To do this effectively, the CEO and executive team need to define the organization’s future leadership requirements, identify promising internal candidates, and provide the right doses of stretch assignments, mentoring, formal training, and performance assessment to grow their capabilities. Organizations can start small, perhaps focusing on supporting a few emerging leaders, and then build momentum and systematization over time, putting processes in place for the broader organization. There are resources available to help organizations do this well—including Bridgespan’s Nonprofit Leadership Development toolkit, and AchieveMission’s Nonprofit Human Capital Management Resource Center.

Executives also should be candid about their need for grants to help build the skills and capacity of the organization to do talent management well and to have the resources to supplement on-the-job learning and mentorship with high-quality training and support.

Bethany Henderson, executive director at DC Scores, a Washington, D.C., afterschool program for urban youth, asks funders for resources for leadership development for her senior team. “Training and development are just part of our regular management process,” says Henderson. “We give each [manager] a…staff training budget…to give [reports] as many opportunities to learn as possible.” To fund this, Henderson seeks funding earmarked specifically for leadership development. “Earmarking forces your hand in a good way,” she says. “It is often tempting to dedicate all funding to program operations…earmarking it takes it out of the calculus.”

Board members should hold themselves accountable for effective succession planning and work to minimize the risk that their entire leadership team could turnover in the next decade. They need to make leadership development a priority, committing time and attention to making sure the right resources are allocated to leadership and staff development within the organization. They should hold the CEO accountable for prioritizing leadership development within the organization and should work directly with the CEO to ensure she is getting the support to develop and thrive in her role. “When I was promoted to the executive director role, my board was very conscious and deliberate about my development,” says Michelle Freridge, executive director of the Asian Youth Center, San Gabriel, Calif. “The board really worked with me to get the training and support I needed to be successful.”

Funders, too, can help take the inside answer to succession planning—homegrown leaders—off the endangered species list and simultaneously strengthen the organizations they fund. As one funder says, “Having effective leadership is a critical requirement for achieving the programmatic outcomes funders are looking for in their investments.” Effective talent development calls for capacity investments in recruiting, training, and performance measurement, yet 58 percent of our survey respondents had not received any funding earmarked for talent development in the past two years. Notably, only 1 percent of foundation funding goes to leadership development.19

Not only is there a need for more resources, but those investments need to be laser focused on the root causes of turnover, which can differ by the field or context in which those investments are being made. Addressing root causes may steer funders away from supporting traditional approaches, such as fellowships, training, and conferences, and toward helping grantees to build their internal leadership development capabilities, growing talent now and into the future across their portfolio of grantees.

When Bridgespan first projected a rapid rise in demand for nonprofit leaders nine years ago we were concerned that the sector might not be able to find enough high quality leaders to meet the growing demand. Those fears went unrealized, but a different deficit, a leadership development deficit, has exacerbated the revolving door for talent and made it harder to address the sector’s perennial concern, leadership succession. Nonprofit leaders, their boards, and their funders need to begin taking steps to do a better job of developing internal leaders to bridge the leadership development deficit. Only then will the turnover treadmill slow down and succession planning improve.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kirk Kramer, Libbie Landles-Cobb & Katie Smith Milway.