Just over 20 years ago, the iconic management expert Peter F. Drucker published an article in Harvard Business Review entitled “The Theory of the Business.” The essay called for leaders to stop focusing on what Drucker labeled “how to do” techniques, and instead think about three fundamental sets of assumptions related to the organization’s environment, mission, and core competencies. Together, Drucker argued, these assumptions create a “theory of the business.” Importantly, he noted that all organizations, not just corporations, need a “clear, consistent, and valid” theory to succeed. He also pointed out that they need to regularly assess and adjust this theory in response to changing conditions.

Today we need a new “theory of (or perhaps for) the foundation” to help individual organizations articulate and, if needed, revisit their specific assumptions and beliefs about how they function at an institutional level. In fact, some might say we’ve never really had any theory of a foundation that meets Drucker’s criteria. Most writing about large private foundations focuses on their programs and grants, including their results, with little attention to their actual or perceived operating environment or competencies. Indeed, there has been little examination of foundations as institutions that need to be organized, managed, and led to achieve their full potential (though CEP, GEO, FSG, Institute of the Future, and experts like Tom David are doing some interesting work on these topics).

The need for a theory or theories of a foundation is especially acute now in light of the major changes in the foundation sector’s overall landscape, approach, and activity during the last 10 to 15 years. To highlight just a few changes noted by the many foundation leaders and philanthropy experts we’ve interviewed:

- Many of today’s significant foundations, in many countries, barely existed a decade or so ago, and living donors rather than fiduciaries are actively governing them. Especially in the United States, the number of foundations is growing quickly, and as baby boomers begin to transfer their assets, projections for growth in philanthropic resources look to be very significant.

- Large foundations now tend to express their core purpose or mission as creating social change, or solving problems, rather than as supporting broad charitable purposes. This means that, in effect, they look much more like operating foundations (ones that develop and/or run programs, rather than solely making grants). It also means they are tackling challenges too large for the philanthropy sector—much less an individual philanthropy—to solve independently.

- Leading foundations are more active than ever in partnerships and collaborations, but their operating systems—including grantmaking procedures and allocations to specific program areas—can make collaboration challenging. Donor-led foundations, with their highly concentrated decision-making, operate on very different cycles than independent foundations.

- Impact investing challenges foundations to harness market forces in new ways. This includes significant changes in how foundations work with their external investment advisors, as well as how they connect their program and financial teams.

- Foundations turn increasingly to advocacy and communications—for both specific initiatives and their organizations as a whole—to achieve their strategic aims. How foundations can and should deploy internal and external communications resources varies greatly.

- Foundations’ leadership teams draw talent from a much broader array of sectors (including consulting, finance, and general management), with vastly different core competencies and experiences. This has important implications for culture, integration across areas, and career paths.

- Finally, the social compact that supports private foundations is under pressure in many parts of the world, including the United States. In many places around the world, public sector resources are strained, and while the impression that foundations can fill these gaps is mistaken, it’s nonetheless widespread. The role of foundations as policymakers has long seemed inappropriate to many, and it’s a viewpoint increasingly expressed in the United States, from both sides of the political spectrum. Some policymakers question whether US philanthropy should be able to support as many issues as it does, and suggest that tax policy should encourage philanthropy to support a narrower range of causes, such as saving lives.

In brief, foundations as institutions are in flux. Yet the implications for their operations, organizational capacity, and efficiency remain largely unexplored. Not surprisingly, leaders of both new and established foundations are looking for new frameworks and models to align resources—both internally and with other organizations—and achieve impact at an institutional level. Indeed, nearly every CEO of a large foundation would agree that a foundation is not just about its grants. But then, what is it about? What is our theory of a foundation?

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Such a framework would enable leaders of both new and well-established foundations to envision and then implement a strategy for the 21st century, inform new foundations as they build their organizations, enable more effective engagement with other sectors, and enhance the capacity of foundations to align their internal resources to achieve impact.

Examining Other Theories

Before turning to a framework for a theory of a foundation, it's worth reviewing theories developed for other kinds of entities, in particular large public corporations, public sector entities, and family-owned businesses. Each offers interesting parallels and helpful insights for foundations, but also reveals gaps that explain why the foundation sector needs a theory and frameworks of its own.

1. The public corporation theory—with its focus on mission, core competencies, and environment—seems most appropriate for foundations with the freedom to choose and change their playing fields and terms of engagement; it's also useful to those who see themselves as having strong competitive advantages, a deep commitment to a logic model, and a more general theory of change. Foundations with strong, corporate-style CEOs and management teams also align with this theory.

Drucker's arguments for the centrality of an organization's theory of itself emerged in an era of rapid change in the corporate landscape—indeed, his observations seem to foreshadow the notion of disruption described in Clay Christensen's The Innovator's Dilemma. Drucker noted that while many companies were doing the right things and doing things right, the "assumptions on which the organization has been built and is being run no longer fit reality." These assumptions, he asserted, "shape any organization's behavior, dictate its decisions about what to do and what not to do, and define what the organization considers meaningful results." Organizations need to base their assumptions on reality, make them internally consistent and understood, and test them regularly.

2. The public sector theory—incorporating legitimacy, capabilities, and public value—seems most appropriate for foundations with mandates they cannot readily change. This includes community, conversion, and single-issue trusts and/or foundations. Similarly, rights-based, grantee-centric foundations fit this theory, because they define their legitimacy through the individuals and groups they support. Cultures (especially outside the United States) that define foundations' role more narrowly also implicitly use this theory. Even in these cases, however, a foundation isn't subject to the political pressures of an actual government agency.

Another way to look at an endowed foundation is to compare it to a public sector agency: It has funding from one source, along with a mandate to benefit a somewhat different group of stakeholders. At the governance level, there's broad authority over the allocation of funds. The amount of those funds doesn’t directly relate to market, investor, or consumer choices. It’s answerable to society (not just its investors and customers), but many of its constituents have little control over its priorities, decisions, and actions. It’s supposed to produce public value, but as in the foundation sector, defining that value is extremely challenging.

The model depicted above, articulated by Mark Moore of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, captures this dynamic very clearly.

3. The family enterprise theory—which adds family factors to the typical business model—is most appropriate for a founder-led foundation, one with a strong legacy that defines decisions or a highly engaged (family) board. It also offers interesting advantages for a foundation with a powerful advocacy orientation based on core beliefs.

A family enterprise can, in effect, choose its own path and mission while ignoring market forces, as long as family members are content with the results. Many privately owned wineries, for example, are true nonprofits whose owners remain willing to underwrite them, and not simply for tax planning purposes. The same can be said for some publishing enterprises. Even when the family enterprise seeks to make a profit, as most assuredly do, its owners have a degree of flexibility that most publicly traded companies do not.

In this model, it's clear that the family's vision is the central force, and two of the four important factors surrounding the vision relate to the family. Interestingly, this theory of a family enterprise separates official family protocol, or governance, from less-formal family factors, including personal dynamics and family members' financial status. In many family enterprises, the need for liquid assets by one or more family members can dictate the fate of a company, as can the absence of an agreed-on successor.

Theory of a Foundation

Useful as these analogies are, it’s worth framing a theory specifically for foundations, rather than cutting and pasting from theories developed for different types of organizations. The foundation is a very particular type of institution, even though it's eluded serious definition. In fact, the definition of a foundation that resonates best is a flippant one: “a large body of money completely surrounded by people who want some” (from Dwight Macdonald’s book The Ford Foundation: The Men and the Millions). A foundation exists because of a social compact that allows private resources to be privately controlled for public benefit. How this compact evolves, and how the foundation operates within it, is fundamental to its theory of itself.

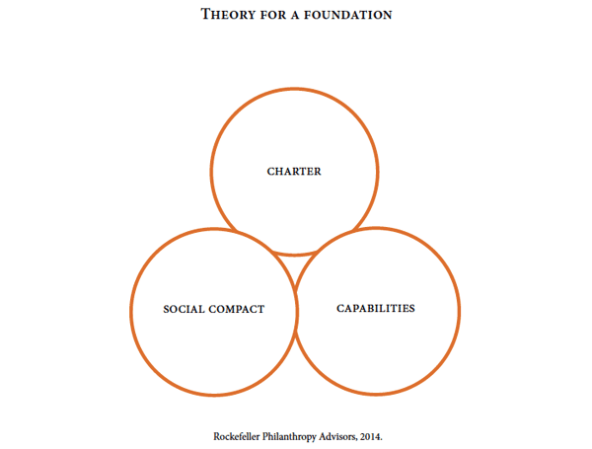

Based on the unique attributes of the sector, a theory for a foundation must include the following:

1. Charter describes the foundation’s form of governance and decision-making on both formal and informal levels. It’s the precursor to mission and creates the organization’s culture. The field of philanthropy informally distinguishes private foundations by whether they are family or independent, implicitly recognizing that governance plays a major role, but this theory of a foundation establishes these differences as central.

Charter refers not only to what is explicit in a foundation's founding documents and founder's vision, but also to the commitments and choices of subsequent stewards, including CEOs, senior leadership, and boards. The foundation's charter may be practically a blank slate, a set of values and principles, or a prescribed area of activity. In other words, some foundation stewards may revamp the charter based on what they observe; other foundations may view it as a mandate to honor forever. For a living donor’s foundation, it’s essentially what the donor is committed to, which may change. It may describe areas of activity (such as the arts, Cleveland, or children), or it may be a set of cultural values. It may include traditional elements of mission, but can go beyond that to incorporate values and culture.

The written and unwritten elements of the charter define how a foundation makes fundamental decisions—and perhaps more importantly what decisions it cannot make. A few examples:

- One foundation president we interviewed said, "I can't imagine that we'd ever not have an environmental program." This implies that strategic planning discussions at the board level would deal only with how to shape the environmental program, not whether it should continue.

- Some foundations eschew advocacy work. There may be no written policy to that effect, but everyone acts as if there is such a prohibition. The unwritten charter of the foundation, everyone understands, makes it off limits.

- Does each new area of potential activity start with an in-depth landscape scan and analysis? Or does an individual program officer perceive an opportunity and move quickly to engage the foundation? Does the communications team come in at the beginning or end of an initiative?

These distinctions in the unwritten charter determine not only what kind of talent is likely to flourish, but also what challenges will ensue when foundations with fundamentally different approaches try to collaborate. Many parts of the charter can change or evolve, of course, but that requires awareness, planning, and organizational focus.

For some foundations, the charter (written and unwritten) looms over everything about the foundation and remains its lodestar; for others it’s an evolving concept, while important over time in defining values and legacy. For those with strong charters, any important decision must align with the charter. For those with open charters, a check of general principles will likely suffice. As always, the vast majority in the middle will often face ambiguity.

At any given moment, a foundation’s charter will be at some point along this continuum—although a foundation’s position on this continuum may shift to the right (usually) over time:

Donor-led > Stewarded > Connected > Open

- Donor-led: A living donor sets mission, priorities, resource allocation, and forms of engagement. These may change as the donor’s thinking evolves. Examples include Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Simons Foundation, and Oak Foundation.

- Stewarded: This type of charter is founder-determined; while the donor no longer lives, their decisions continue to shape the foundation’s mission, program areas, and approach, whether legally or by custom. Subsequent boards and leaders operate within the founder’s framework. They see themselves as stewards and guardians. Examples include Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies, the Robert Bosch Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

- Connected: The founder’s vision, preferences, and approach guide but do not tightly constrain the successors—whether family members or not. Successors see themselves as interpreters of tradition; continuity is important, but expression (in terms of issue area, approach, involvement, and other factors) can evolve. Examples include the Surdna Foundation, the Wallace Foundation, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

- Open: Board members—whether descendants of the founder or not—feel empowered to select the foundation’s areas of activity, and types of engagements based on their collective assessments of external forces and the foundation’s capacity. There is no felt need to ask how the founder might have reacted to present decisions or to adhere to a traditional area of work for the sake of continuity. They may view tradition as a strategic advantage that they should not readily abandon, but base their decisions on objective assessment of a resource, not value-based loyalty to the past. Examples include the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

The first and fourth of these—donor-led and open—are the most sharply delineated, of course. The distinction between stewarded and connected may be in the eye of a beholder, and is an area of constant evolution in any foundation. But there is a meaningful difference, we believe, between the scope of decision-making between the two. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, for example, will not pivot from health care any time soon; the Annie E. Casey Foundation will remain devoted to low-income families, but its approach to helping them might change radically based on emerging opportunity and shifts in the environment.

2. Capabilities go beyond the traditional core competencies to include the resources, skills, and processes that the foundation also cultivates in its sphere of activity. Unique among institutions, a foundation’s financial base does not just enable its activity—it’s a form of activity or output. The concept of capabilities also encompasses how a foundation assesses and responds to its environment. Thus, capabilities tend to evolve over time.

Classically, foundations focused on a narrow set of capabilities: domain expertise in program areas, or professional expertise in supporting functions like investing, communications, and human resources. But many foundations are moving away from defining themselves as engines to support grantmaking. Rather, they are (and in some cases have been for decades) often deeply engaged in designing solutions, spotting talent, building coalitions, and using their voice. Grantmaking is a part of these approaches, but other functions are extremely important. And each of these approaches to making change implies a different set of skills, knowledge bases, and networks.

In some cases, a foundation may need to have different capabilities in different program areas—although one might wonder how the demands implicit in this approach might limit the success of a foundation at an institutional level. Lessons from the corporate sector suggest that no organization can be first-rate in all areas. Indeed, that's the question that every highly diversified corporation has to answer: What value is the management team overseeing a portfolio of business units that includes engines, salad dressing, and concert promotion creating?

Many large foundations have indeed narrowed their scope and span since Michael Porter and Mark Kramer asked the question in their Harvard Business Review article, “Philanthropy’s New Agenda: Creating Value.” But the question continues to deserve debate and attention. Many foundations can group their programs into a handful of broad issues areas (such as the environment or education). Nonetheless, at the program level, they, in effect, may be operating dozens of distinct units.

The foundation leaders we interviewed were looking to find the right balance for capabilities along five fundamental-but-different spectrums:

- Decentralized vs. centralized

- Builder vs. buyer

- Creative vs. disciplined

- Broad vs. deep

- Independent vs. networked

Naturally, there is no right place to be on any of these spectrums, but an individual foundation’s answers have implications for its operating model, organization design, staffing, and assessment of meaningful results.

3. Social Compact encompasses how a foundation defines its license to operate, the value it creates, its accountability, and its relationship with stakeholders. It’s the source of the foundation's legitimacy in the ethical, if not the legal, sense. (A foundation's charter, as noted above, describes its internally created legal restrictions.) Social compact answers the fundamental question: How are we making a difference with the special status accorded to us, and how do we need to demonstrate that?

Characteristics of a foundation’s social compact include:

- The foundation’s understanding of what’s appropriate for it to do, beyond the minimum required by legal and regulatory frameworks

- How the foundation interacts with stakeholders, including its commitment to “explaining itself,” or transparency

- The foundation’s commitment to understanding and communicating “meaningful results,” as Drucker put it. (Note that he did not say “measurable results.”)

More tactically, some foundations choose to spend well beyond their minimum and/or spend down. Some foundations participate actively in the civic life of the city where they are based; others see no need to do so.

While some of a foundation’s social compact is externally imposed (as are economic conditions), how an individual foundation interprets that compact is distinctive. In essence, the question comes down to: To whom are we responsible? In outlining this part of its theory, a foundation could articulate that it’s responsible to one or more of the following:

- Its founding legacy, board, and legal/regulatory authorities.

- A group of beneficiaries or a region

- A cause or issue

- A set of principles and values

- Grantees

- A broad range of stakeholders—such as communities, media, the philanthropic sector, and/or the general public

Conclusion

Foundations are playing an increasingly important role in solving social problems, and they are both emerging and evolving in diverse, fascinating ways. Mapping out a foundation's theory for itself as an institution offers a way to clarify how it makes choices, allocates resources, and defines its success. The process can also create a shared vocabulary for both board and staff, and can illuminate important distinctions and commonalities among foundations. A foundation's theory of itself should shape how it does its work, as well as how it's structured, staffed, and networked.

Having a theory for a foundation will also give the sector a way to compare and analyze models, assess how it allocates resources, and seek links between how a foundation operates and what results it achieves. To achieve their potential, especially as resources and expectations grow, foundations must commit to examining how they function as institutions.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Melissa A. Berman.