Young people from Parkland, Florida, and other cities onstage at the March for Our Lives protest in Washington, D.C., on March 24, 2018. (Photograph by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images)

Young people from Parkland, Florida, and other cities onstage at the March for Our Lives protest in Washington, D.C., on March 24, 2018. (Photograph by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images)

As the United States moves deeper into the 21st century, our democracy’s most fundamental principles are under challenge. Headlines proclaim the widening divide between Republicans and Democrats over immigration, the environment, race, and other critical issues. The gap has more than doubled since the Pew Research Center began tracking political values in 1994.1 Congressional gridlock has increased exponentially over the past 60 years,2 draining our elected leaders’ capacity to solve the nation’s biggest challenges. Even as the stock market climbed to record levels through 2017, the odds that children will earn more than their parents—the essence of the American Dream—have declined steadily since 1940.3

A handful of bold philanthropists—on the left and the right—are stepping into the breach, with outsized investments to influence civil and political society. eBay Inc.’s founder, Pierre Omidyar, pledged $100 million to address the root causes of global mistrust. Charles and David Koch are spending $400 million to influence politics and public policy.

Leaders like Ford Foundation President Darren Walker have urged peers to summon the moral courage to confront social and racial injustice.4 Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan ensured a robust policy platform for their Chan Zuckerberg Initiative by hiring David Plouffe, former President Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign chairman, and Ken Mehlman, former President George W. Bush’s 2004 campaign manager.

Nevertheless, politically active philanthropists remain the exception, not the rule. Many we meet with still wish to stay above the political fray, even on issues they care about passionately. To them, the nation’s tectonic shifts feel enormously threatening. Many still stick to scripts from a bygone time. “We don’t do advocacy” is a common refrain. “The family members on our board don’t want us to ‘get political.’” Or, “We’re worried about our issues, but we’re also afraid of losing our charitable status if we engage politically.”

Their fears are real. Think of how opponents aim withering fire at the Koch brothers or George Soros. But the good news is that philanthropists can avoid brutal political combat and still engage the public and policy makers. There are powerful, safe avenues to advance critical policy issues such as providing justice for sexual assault survivors, ensuring that all Americans have access to green space, and combating the mass incarceration of African-American men. Many (though not all) of these issues can be tackled in a bipartisan or nonpartisan approach.

Indeed, Americans increasingly look to the nonprofit sector to help put the country on a path to progress. A 2016 Independent Sector poll found that 78 percent of voters “support a bigger role for the charitable sector in working with the federal government to produce more effective and efficient solutions to problems.”5 The survey also found that 70 percent of voters are more likely to back a presidential candidate who supports the charitable sector’s involvement in government policy making.

To be sure, philanthropy has a long and honored history of advocating for social causes that span the political spectrum. Bridgespan Group research reveals that philanthropic “big bet” grants of $10 million or more figured in a majority of social movement success stories. In one study of 14 historic social movements—including conservatism’s rejuvenation during the 1970s and 1980s and the rise of LGBT rights over the past decade—more than 70 percent received at least one pivotal big bet.6

In another Bridgespan study of 15 successful, breakthrough initiatives—such as ending apartheid in South Africa and improving working conditions and wages for US migrant farmworkers—80 percent of those philanthropic efforts required changes to government funding, policies, and actions, rather than a plucky entrepreneur or single donor going it alone.7 However, the data suggest that philanthropists can do far more.

In 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, US foundation grants for policy and advocacy totaled just $2.6 billion, slightly more than 4 percent of $60.2 billion in total giving. Those data roughly correlate with Bridgespan’s research. Of the 10 most prevalent ways to bet big on spurring social change, “wage an advocacy campaign” accounted for just 4 percent of more than 900 gifts (collectively valued at $22.7 billion) from US donors.8

There is little doubt that many want to do more: A Center for Effective Philanthropy survey found that more than 40 percent of US foundation CEOs say they intend to increase their emphasis on advocacy and public policy at the state and local levels.9 Additionally, 50 percent of foundation leaders see opportunities resulting from Donald Trump’s election as president. These CEOs most frequently cite “increased engagement and activism” as the biggest opening of all.

Philanthropists have a responsibility not only to protect their reputation, but also to achieve their mission. Too often, concern with preserving the former can kill the will to advance the latter. Despite an understandable reluctance to step anywhere near today’s pernicious political landscape, philanthropy has a once-in-a-generation opportunity to engage powerfully in more—not less—advocacy.

Five Questions for Philanthropists

If philanthropists are going to step up their advocacy work, what is the best way for them to proceed? For nearly 20 years, Bridgespan has counseled scores of the world’s most generous and ambitious philanthropists. Similarly, the bipartisan Civitas Public Affairs Group, which works at the intersection of philanthropy, politics, and policy, has for many years advised some of the country’s most successful nonprofits and visionary donors on how to build and execute advocacy campaigns.

We are struck by the dramatic uptick in interest from philanthropists who are feeling the pressing need to support advocacy efforts but are also unsure of how to take the next step. Our work, as well as our conversations with leaders of every political stripe, has persuaded us that if philanthropists are to advance the issues they care about, they will have to honestly reckon with five critical questions:

- Do you know the rules of engagement?

- Who is your opposition?

- Have you converted strategy to an opportunity map?

- Are your messages aimed at winning new allies or just making your base feel good?

- Are you using new technologies to educate and advocate?

In the rest of this article, we’ll examine each of the five questions in detail and explore how funders and nonprofits have used them to effectively mobilize campaigns.

Question 1: Do you know the rules of engagement?

The US Internal Revenue Code gives institutional philanthropy significant latitude to have a point of view on policy outcomes. Federal law allows nonprofit organizations to participate in a mix of direct lobbying, grassroots mobilization, policy development and implementation, voter registration and get-out-the-vote efforts, and candidate forums. Many nonprofit organizations, however, are unaware of (or fail to utilize) their legal capacity to directly interact with the leaders of federal agencies, governors, and mayors, who have the power to work on their behalf.

Philanthropy’s blind spot for what’s possible in policy making surprises veteran attorneys such as Joe Birkenstock, a partner in the Washington, D.C., law firm Sandler Reiff Lamb Rosenstein & Birkenstock, P.C., which advises entities at the intersection of philanthropy and politics. “I’m stunned that people don’t know the new rules of engagement. Many people who have done philanthropic work for decades are not fully utilizing the tools that their opponents are.”

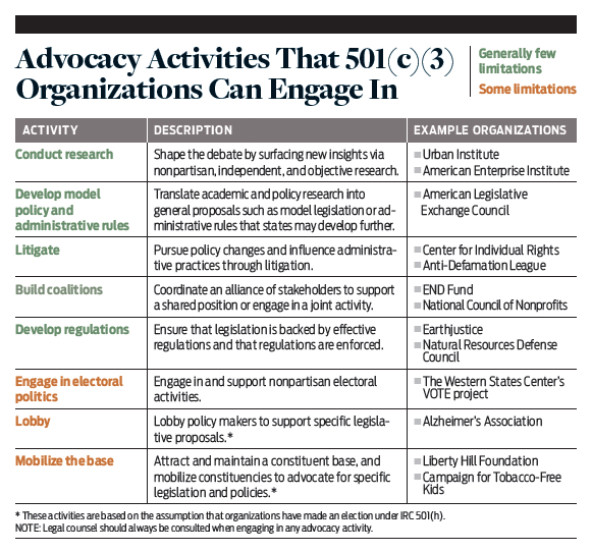

The Internal Revenue Code prohibits public charities from engaging directly in campaigns on behalf of candidates for public office. But that prohibition recently has been targeted for substantial amendment or even outright repeal. Even if that restriction remains unchanged, there are no such constraints on cause-related advocacy. (See “Advocacy Activities That 501(c)(3) Organizations Can Engage In” below.)

That’s why 501(c)(3) nonprofits across the political spectrum have made it a point to become conversant with the tax code and the full range of available tools to advocate for issues that matter and shape public policy. Case in point: Even as more and more women have shared their stories of sexual harassment to the hashtag #MeToo, the Joyful Heart Foundation has taken up the challenge of helping sexual assault survivors heal. Seizing on the unacceptable reality that hundreds of thousands of sexual-assault evidence kits, otherwise known as “rape kits,” remain untested in crime labs across the country, Joyful Heart unleashed a nationwide advocacy effort to end the backlog. The grassroots-funded nonprofit, founded in 2004 by actress Mariska Hargitay, has pushed for the introduction of rape-kit reform bills in 34 states; 19 states have thus far signed them into law. Other examples from both ends of the political spectrum:

- The Urban Institute and the American Enterprise Institute conduct research to surface new insights and influence policy debates.

- The Liberty Hill Foundation and the Campaign for Tobacco- Free Kids build and mobilize constituencies to advocate for legislation that advances their missions.

- The Center for Individual Rights and the Anti-Defamation League pursue policy changes though legal advocacy and litigation.

Even if donors and grantees decide to

stay above the fray, it's almost guaranteed

that their opponents won't.

It behooves leaders of foundations to recognize that grantees have leeway to influence legislation and public opinion. Public charities that push into the policy arena can protect their tax-exempt status by employing the “H Election”—otherwise known as Section 501(h) of the Internal Revenue Code—which protects the rights of charitable organizations to lobby, so long as they don’t exceed specific dollar limits.

Charitable organizations can also create companion 501(c)(4) entities that seek to shape legislation and, through limited participation in electoral politics, hold lawmakers accountable for their policy decisions. A key stipulation: The organization’s lobbying efforts must align with its mission. For example, the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a 501(c)(3) that’s composed of conservative legislators and corporate leaders, created ALEC Action. This 501(c)(4) “advocacy partner” works to shape state-based legislation that promotes free-market policies and less government oversight.

Through ALEC Action, ALEC’s conservative and libertarian funders are leaning into their mission and advocating for legislation that aligns with their beliefs. ALEC Action has pushed federal lawmakers from West Virginia to North Dakota to repeal the Affordable Care Act and return health-care decision-making power to their states. ALEC’s advocacy efforts at the state level go far and deep: Through its website, social media, and broadcast and print news outlets, the organization’s messaging reached 35 million Americans in 2016.

Unfortunately, we’ve seen large foundations actually discourage grantees from getting anywhere near the nexus of advocacy and policy work, when they could be providing grantees with general operating support and legal resources to increase activity—all while staying on the safe side of the line. Foundations could even ask grantees to document how they’re using the tools at their disposal to make positive change. They could analyze (internally or with external help) the ways they themselves can fund or execute on issue advocacy legally, and with high impact. Every donor and board member could consider asking for regular updates on whether the entities they support and advise have maxed out on their ability to do advocacy work.

“People should recognize the need to do things differently if they want to get different results,” Birkenstock argues. “There’s never been a better time to challenge the assumptions baked into the ‘but this is how we’ve always done it’ approach.”

Question 2: Who is your opposition?

If you don’t think that your selfless, public-spirited cause has opponents,

think again. Newton’s third law of motion—for every action,

there is an equal and opposite

reaction—applies as much to the physics

of philanthropic advocacy as it does to the properties of matter

and energy. Ignoring the fundamental fact that “forces always come

in pairs,” few organizations expend enough time exploring how their

endeavors might spark opposing efforts. Nor do they marshal sufficient

resources to counteract the inevitable pushback.

At first glance, the national nonprofit Autism Speaks had every reason to believe that a bill it was supporting in North Carolina would win approval in the state’s General Assembly. After all, it aimed to require certain health plans to cover an effective treatment for helping kids with autism, called applied behavior analysis (ABA). Conventional wisdom held that few elected officials would turn their backs on autistic kids. In fact, the proposed legislation seemed to have broad bipartisan support. In both the 2013 and 2014 sessions, North Carolina’s House passed bills that included ABA coverage. But each time, the legislation failed to gain traction in the state Senate.

“Something just didn’t add up,” recalls Liz Feld, formerly the president of Autism Speaks, who brought years of advocacy and political experience to her role. “North Carolina had always been a leader in autism research, so it was hard to believe the legislature would not help these families.”

Feld and her colleagues knew the insurance industry generally opposed comprehensive legislation requiring them to cover treatment for autism: “We had been battling with insurance companies all over the country, so we were used to corporate firepower pushing back on our legislation.” But when the organization dug deep into publicly available lobbying disclosure reports, it discovered that in 2014, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina had spent more than $485,000 on lobbying the state government. Even without knowing what portion of that amount went specifically to lobbying on autism, the magnitude of the spending signaled to Autism Speaks that insurers had leverage with North Carolina lawmakers.

To be sure, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina has done much to improve the health of the state’s citizens. This year alone, the company is investing millions to fight opioids and support other health initiatives across the state. But even good corporate citizens, with their own reasons, will sometimes oppose a worthy social goal.

Having confirmed that large insurance companies were likely responsible for helping to stall autism legislation, Autism Speaks could then mount a two-pronged counteroffensive. To win over elected officials, the organization commissioned a statewide poll, which found that 82 percent of North Carolina voters supported autism insurance reform. The organization then developed a messaging campaign highlighting fiscally conservative reasons for the Republican- controlled legislature to support the bill.

At the same time, Autism Speaks launched an ad campaign that directly took on “Big Insurance” in North Carolina. The data-rich ads countered insurers’ two main arguments: that they were already adequately covering autism, and that expanded coverage would burden small businesses. The result: progress. After a series of negotiations between activist organizations including Autism Speaks, insurers, and state legislators, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina dropped its opposition and helped shape an autism reform bill that included coverage for ABA, which the General Assembly approved. Although many factors contributed to the turnaround— not least of which was the autism community’s grassroots work to build support for the bill—Autism Speaks’ concerted effort to identify, target, and ultimately work with the opposition played a pivotal role.

“We had been working to get amazing families, from hundreds of miles away, to the State House to advocate for an end to discrimination for people with autism,” says Feld. “But we didn’t really level the playing field and have a chance to win until we did opposition research.”

Question 3: Have you converted strategy to an opportunity map?

It’s hard to imagine a charitable organization that doesn’t regularly strategize on how it will direct resources and prioritize programming. And yet, few organizations do real-time advocacy opportunity mapping, the bedrock of building short- and long-term advocacy efforts.

Policy change does not occur in a vacuum, nor can any single leader, donor, or organization go it alone; understanding and anticipating the dozens of moving parts in any attempt to advance social change is essential to planning and executing a winning campaign. Mapping a campaign’s features and fissures gives a nonprofit’s leaders, donors, and board members a clearer understanding of the logic behind certain investments and why particular regions or states should be prioritized over others. It also injects a campaign-like mentality—as well as urgency and accountability—into the day-to-day grind of working toward a lofty goal.

In many ways, advocacy is rooted in cartography. Protagonists delineate the advocacy effort’s topography, trace the links between key players, identify opportunities, and plot potential pathways to achieving the desired change. Of course, mapping can also be applied to physical geographies, such as a state or a region. When they bring such a map to life, practitioners draw out critical information, such as a state’s political makeup, pending litigation, pertinent legislation and laws, opposition forces, and allies and coalitions—the elements of a cogent strategy.

Such was the case with the Trust for Public Land (TPL) when it took on the challenge of ensuring that there’s a park within a 10- minute walk of every person, in every city and town across America. As TPL began to conceive its “10-minute walk” campaign, one of its first initiatives was to map park access across the entire country. Through this mapping and other research, TPL determined that more than 100 million Americans lack nearby access to public green space, which is vital to a community’s environmental health and well-being.

TPL also created an opportunity map of existing stakeholders, natural constituencies, and potential allies. Through its analysis of the campaign’s landscape, TPL identified mission-aligned organizations, such as the National Recreation and Park Association and the Urban Land Institute, that could help build a platform for coordinated action.

The map also revealed an opportunity to more deeply engage with an under-targeted but critical group—the nation’s mayors—through avenues such as the US Conference of Mayors. By identifying and enlisting a core group of mayors to anchor the campaign, TPL reasoned that it could build momentum and convert more mayors in additional target cities. So it was that in October 2017, when TPL and its partner organizations launched their parks advocacy campaign, they had already enlisted a bipartisan group of 134 mayors in cities spanning the country, from deep-red Cody, Wyoming, to bright-blue Burlington, Vermont.

An opportunity map synthesizes key information in a clear and concise format and plots out pathways for fulfilling advocacy goals. For example, if the ultimate goal is to pass legislation, a map can illustrate the fact that before a strategy can be implemented, the organization first needs to change people’s minds and build a more potent base of support. A landscape analysis can also help strategists determine whether a smart first step would be to target a specific city or neighborhood, or reveal something as simple as whether there are enough votes to carve out a path to victory.

In addition to mapping an external landscape, a landscape analysis can help nonprofits look inside their own organizations and map out networks of internal power brokers. Such a process identifies the relationships between critical stakeholders who have the throw-weight to advance a policy agenda. Often, organizations that support or participate in advocacy fail to fully utilize boards of directors and C-level executives, and their nearly boundless webs of contacts. Even within your own organization, there might be more political power than anyone realizes.

Question 4: Are your messages aimed at winning new allies or just making your base feel good?

Through regular updates, email alerts, and other communication avenues, most effective organizations excel at crafting messages that animate their donor base and activist stakeholders. But that’s not enough. Advocacy and education work can quickly break down when organizations fall into the trap of using language that solely rallies supporters, instead of shaping messaging that also resonates with people who doubt a cause’s primacy or efficacy but might still be persuaded to lean into it. And we know that language matters, a lot—consider “death tax” versus “inheritance tax,” and how advocates used the grim-sounding term to galvanize forces around an esoteric policy debate.

When an organization plays exclusively to its base, it risks creating an echo chamber for true believers, rather than pitching a tent that is big enough to accommodate converts. On the surface, it might appear that undecideds are few and far between in today’s hyperpartisan political climate.

Digging deeper, however, the evidence suggests that the American public is more united than commentators would have us believe. For example, although Americans are sharply divided over the tension between gun rights and gun control, a 2016 survey commissioned by The New York Times found overwhelming support among registered voters for specific, individual proposals, such as universal background checks on gun purchases.10

Common ground can prove fertile for organizations seeking to grow beyond their base, even when the cause is guns or some other high-temperature issue. Those social sector entities that succeed at honing emotionally resonant messages for skeptical but swayable audiences begin by polling, so as to better understand the target population’s desires and concerns. They also use focus groups to test language and zero in on messaging that works.

Such was the challenge that Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions (CRES) encountered when it reached out to Republican policy makers on issues affecting the environment. Until recently, policy designed to preserve and protect the environment was seen as a common good.11 Over the past two decades, however, issues involving the environment have too often divided political parties. And few environmental issues are more divisive than global climate change.

Founded in 2013, CRES is a 501(c)(4) nonprofit with an affiliated PAC and a separate 501 (c)(3) (CRES Forum) that works to promote clean-energy policy solutions that can win conservative allies. The organization exclusively supports Republican policy makers and candidates who support clean energy as a way to preserve the Earth’s climate. But in the months following its launch, CRES ran into strong headwinds. The issue had become too politicized.

At the time, there was little to no polling to test the kind of climate-related messaging that might activate conservatives. Seeking to enlist support for clean-energy policies from Republicans skeptical of climate change, CRES sought to find new messaging frameworks by consistently polling target audiences. The research showed that conservatives viewed scenarios depicting the consequences of rising global temperatures as doom-and-gloom fearmongering. But some among them connected with messages like “Being responsible stewards of God’s creation” and “Creating new jobs and a stronger economy based on clean, renewable energy.”

That’s only a start. But the first green shoots of progress just might be starting to sprout. Last year, even as the United States withdrew from the Paris climate accord, the US House of Representatives’ bipartisan Climate Solutions Caucus more than tripled in size. CRES worked with Republican leaders in the US Senate and House to form working groups, whose aim is to develop conservative clean-energy policies. For example, three conservation-minded Republican senators cast the deciding votes to defeat a congressional effort to overturn an Obama-era methane regulation. Out of 15 Congressional Review Act efforts to repeal regulations advanced by the Obama administration, the vote on the methane rule was the only one not to be approved in the Republican-controlled Senate.

Converting skeptics sometimes requires contrarian thinking. If an organization has been using the same pollster for a long period of time and getting the same results, it might be smart to give someone else a chance to surface new perspectives. If a progressive organization truly aims to win over independent and right-of-center voters to its cause, it might try hiring a conservative or bipartisan polling firm, just as a conservative-leaning nonprofit might be wise to hire a progressive pollster.

Of course, it is quite possible that the best messaging framework to win over undecideds might irritate existing supporters. To reduce the friction that comes with expanding the base, successful donors, grantees, and movement leaders work through the problems that may arise when trying to move on-the-fence supporters and policy makers into the plus column.

Question 5: Are you using new technologies to educate and advocate?

Emerging technologies allow an organization to directly engage with potential supporters and influencers who affect an advocacy campaign’s outcome. By using social listening technologies, which track conversations around specific phrases, an organization can quickly glean who’s talking online about an issue, what they’re saying, and how opponents are messaging on the other side.

In real time and for little money, apps like Hashtagify.me and RiteTag pull data from Twitter and Instagram and generate listening reports, which can reveal opportunities to create messaging for influencers and winnable audiences. When we plugged in #Autism on Hashtagify.me, two unexpected hashtags—Etsy and handcrafts— billowed up into its word cloud of related hashtags, while RiteTag listed #Autism’s top 10 most prolific tweeters.

Other technologies in online polling, like Typeform and Poll Everywhere, allow an organization to test, in real time and at a fraction of the cost of traditional polling, whether a message is resonating. Using this research, an organization can target compelling messages to specific zip codes, city blocks, or even individual buildings, and thereby reach the people who are ultimately inclined to support a cause. At the same time, familiar technologies, such as microsites, can help advance an advocacy campaign’s cause.

Such was the case in the summer of 2014, when Autism Speaks launched a microsite, Autism Champions, a temporary campaign to help pass the federal Autism CARES Act.12 The platform enabled the autism community’s most passionate advocates, with just one click, to write, tweet, or connect via Facebook with key legislators. (The site included a personal page for every single member of Congress and had the capacity to reach state and local leaders.) The site gave Autism Speaks a way to rally the community’s champions—district by district and zip code by zip code—with take-action messages at decisive moments. After just a month of activity, the site reached more than 1.5 million people, 178,000 of whom took such actions as sharing, posting a comment, or clicking through to the Autism Speaks website from the Autism Champions microsite.

Whether it’s a platform featuring direct pathways to policy makers and influencers, or a digital portal that lets organizations peer into people’s attitudes and influences, such tools require donors to think differently about the role that advocacy (and funding advocacy efforts) plays in their overall portfolio. One litmus-test question: If your grantees aren’t using smart technologies to target and test, how do you measure whether their messages are connecting with the audiences that matter most?

Applying the five questions

Even though Washington, D.C., is often locked in ideological warfare, not all trenches have been dug. There are wide-open opportunities for philanthropists to help grantees step into the public arena, educate lawmakers, and influence legislation that mobilizes their social impact missions. Think about unlikely pairs such as US Senators Cory Booker, a Democrat, and Rand Paul, a Republican, teaming up to introduce legislation to help nonviolent offenders reintegrate into society. Or organizations like entrepreneur Gary Mendell’s Shatterproof, which is recruiting elected officials on both sides of the aisle to beat back the nation’s opioid crisis. And then there’s hedge fund manager Paul Singer, founder of Elliott Management Corp. and a self-described Barry Goldwater conservative, who crossed party lines and teamed with software entrepreneur Tim Gill, founder of Quark Inc. and a longtime supporter of Democratic politicians, to help win marriage equality for LGBT Americans.

To begin, donors can ask grantees and boards how far they’ve advanced their core issues, what it will take to get where they need to go, and when and where a broader systems and social movement lens is needed. The five questions can act as signposts for navigating those conversations and assessing progress. The questions can also help reveal opportunities that are ripe for development, such as converting research into game-changing policy or marshaling activist stakeholders.

There will also be opportunities for philanthropists to support advocacy campaigns at each stage of their evolution. Every campaign goes through a growth process, which calls on grantees to summon different capabilities. Early on, there might well be a need for philanthropists to invest in momentum-building activities—such as developing a body of academic policy research or a base of grassroots supporters—that build a foundation for progress. As the initiative moves into the public sphere, there’s often a need to invest in coalition building and further solidify the case for change. During the closing effort to finalize a policy change, there will likely be opportunities for philanthropists to plug unaddressed strategic gaps or fuel a lobbying campaign.

No advocacy campaign, not even an undeniably virtuous effort to provide life-changing therapy to autistic kids, proceeds seamlessly. Should they take a stand, philanthropic institutions and their grantees might well encounter pushback, will almost certainly endure setbacks, and could risk alienating some stakeholders. But the alternative—hunkering down and focusing on some nice-to-have but nonessential initiatives that could never become a target for criticism—likely extracts a far bigger price.

Choosing not to engage publicly on issues that matter is still a choice, which comes with consequences. Even if donors and grantees decide to stay above the fray, it’s almost guaranteed that their opponents won’t. Donors’ inaction increases the odds that their chief causes will suffer reversals as the opposition blocks progress. Strategically, and perhaps even morally, the wisest course of action for donors is to invest in helping grantees champion their missions in the public sphere.

Open-access to this article made possible by Civitas Public Affairs Group.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Patrick Guerriero & Susan Wolf Ditkoff.