Hotel Africa: The Politics of Escape

G. Pascal Zachary

342 pages, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012

The following is an excerpt from the book.

Chimpanzee Politics

In the African bush, Dr. Speede considers her biggest achievement not to be a Goodall-like understanding of chimpanzee behavior but rather a clever bit of primate social engineering. She’s helped to create new social groups out of disparate chimpanzees who – left on their own – would tend to mistrust, or even harm, each other. Over the past few years, I’ve seen just how difficult it is to create such social groups. My education began late 2005 when, during a visit to the Dr. Speede’s sanctuary, she received a tip that a baby was available for sale deep in the Cameroonian forest.

Her immediate reaction startled me. At the time, she was busy preparing for an annual festival held at the village nearest to her sanctuary. She’d spent weeks in meetings with locals, planning for the event, which would be attended by chiefs from around the region and even government officials from far away. Managing relations with local leaders a high priority for Dr. Speede. Even though she’s paid local villages for the use of the sanctuary’s land, claims come regularly for additional payments – or for her to deliver enhanced benefits, such as healthcare or schooling to people nearby. The festival is the most visible annual symbol of her commitment to the surrounding African community. She provides food, drink and entertainment – all for the enjoyment of her neighbors and employees.

Only two days before one annual festival, a crisis broke out over whether to serve fish or meat. Dr. Speede is a vegetarian and immediately decided to refuse to pay for any meat served at the festival. On hearing of her decision, the paramount chief grew incensed. Dr. Speede tried to placate him by offering to pay the chief’s friends to catch fish from the Sanaga River. The chief held firm: either he and his friends ate meat at the festival or they would boycott it.

So when she heard that a baby chimp might be for sale, Dr. Speede was understandably distracted. Indeed, she’d planned to spend the afternoon defusing the meat crisis. I selfishly implored her to chase the chimp. She told me that, however tantalizing, these tip came often and most turned out badly.

I asked her to reconsider and she changed her mind, though mainly because this very day a soldier in Cameroon’s special army forces was at the sanctuary. She sometimes received unofficial protection from the army. This soldier was a tall, dignified and fierce-looking, attired in a brown khaki uniform. A pistol was strapped to his waist.

The three of us, and two local employees, set off in a truck. My excitement expired after two hours on dirt roads. Temperatures reached 100 degrees. When we reached the Sanaga River, at a very wide point, we stopped. Waiting for a logging boat to ferry our truck across the river, I suddenly felt foolish and full of regret for sending Dr. Speede – right before her biggest event of the year – on what I feared was becoming a fruitless search.

Overcome with guilt, I told Dr. Speede to call off the hunt. We shouldn’t bother crossing the river. We should return at once to her sanctuary. In the sweltering heat, she looked at me with empathy. “Let’s keep going,” she said quietly.

In the hot sun, on a pier at the edge of the river, we waited for the logging boat. The journey across the river cooled everyone because there was a breeze in the middle of the water. After about 20 minutes, we reached the other side.

Now the driver drove the truck faster. He veered off a dirt road and into tall, thick bush. He barreled ahead, flattened everything in his path. He seemed to know where he was going and I concluded he was either foolishly confident or brazenly lost. Then I wondered how many times before had Dr. Speede come so close to a rescue and then accomplished nothing?

Just when I lost hope utterly, the truck burst into a clearing and nearly ran over a pile of dead animals. Two hunters, their guns drawn, looked at us with astonishment, surrounded by their women and children. Our soldier bolted from the car, gun in hand. Dr. Speede ran after him and then I couldn’t see her any more, my gaze instead fixed on the soldier (whom I stood behind in an effort to secure my own safety).

Honestly, I feared violence. But the hunters spoke calmly to my soldier, and asked whether the foreigners (they actually called us “whites”) had come to buy the chimpanzee. It was then that I saw the baby, tied by the neck to a pole, sweltering in the heat.

I raced toward the chimp, the hunters matching my strides. They were now eager to cooperate. One tried to untie the chimp, but he snarled at the hunter, baring his teeth.

Dr. Speede untied the rope from the baby’s neck. A Cameroonian caregiver, a woman named Marie, collected the chimp against her chest.

For a moment, I pondered how we might detain the hunters. But the soldier decided we should leave, quickly, and we did, driving fast back to the river, the baby in the backseat, bundled against Marie. I marveled at her calm. “He’s a boy,” she said.

While we waited for the boat, Marie stood alongside the river, the baby in her arms. A crowd gathered and she went back into the car.

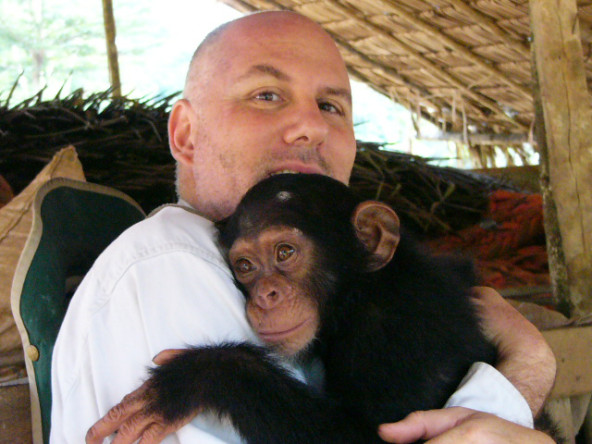

On our return to the sanctuary, two European volunteers took charge of the baby. That night, they slept with him in their hut, acting as surrogate mothers, taking care of his every need. The next morning, the ladies let me hold the chimp and, seemingly by accident, Dr. Speede passed by and casually informed everyone that the baby would be called Zachary, after my surname.

An hour later, Dr. Speede encouraged me to hold Zachary. I resisted but she insisted. Finally, I held the baby chimpanzee in my arms. A caregiver from Europe took our photo, and while she did, as I held Zachary proudly, he urinated all over me.

That was the last time I held him.

More than three years later, Zachary remains in limbo, wary of other infants at the sanctuary, not yet part of a social group. These groups are central to restoring some sense of normalcy to an individual chimpanzee who’s original world has been shattered. That Zachary remains in transition, so long after his rescue, carries a powerful message about the profound destruction occurring to chimpanzee society in Africa – and the long hard road to rebuild these societies.

Just as broken chimp societies must be re-engineered, so must human societies.

There can be no peace for chimpanzees until their human neighbors treat them differently. While outsiders such as Dr. Speede drive the protection movement in Africa, there’s a growing awareness among Africans themselves of the economic, moral and psychological consequences of failing to value wildlife. Janet Museveni, the wife of the president of Uganda and a member of the country’s Parliament, has noted, “It seems futile to me that the rest of the world should know and struggle to protect African wildlife while Africans themselves, the natural stewards of this wildlife, continue to hunt and kill or, at best, remain indifferent to it. This has been the tragedy not only for the animals but for Africa in general.”

To be sure, chimp-loving is associated with Western elitism, yet Africans are changing, partly because conservationists realize animals and humans must benefit together. “When you work with chimpanzees, human need doesn’t supersede our conservation mission,” Dr. Speede says. “They have to go hand and hand.” The elusive solution is to make preservation of forests – and quality of life for chimpanzees – economically sustainable. In Cameroon, as elsewhere in tropical Africa, deforestation occurs because of rising population, demand for lumber both locally and globally, mining exploration, hunting – and the reality that for ordinary people jobs and money are scarce in tropical Africa, driving people who live near forests to use what they can today with little thought of tomorrow.

To help better balance the scale between chimpanzees and humans, Dr. Speede assists schools financially and buys produce from local farmers. She also contributes to a national campaign to make it socially unacceptable to kill, capture or eat chimps. On health grounds alone, the message makes sense; after all, the eating of chimps in Cameroon some 50 years ago is now believed by many scientists to have been the original source of HIV in humans. Habits are changing. “In many parts of Cameroon, eating chimp meat has become taboo,” says Wilson Atteh, a conservation officer in the country’s one urban sanctuary, in Limbe.

Changing attitudes is part of the answer; stronger law is also essential. In Cameroon, a private organization has teamed with government wildlife cops to clamp down on poachers. The arrangement isn’t perfect: Dr. Speede and other conservationists sometimes must pay the costs of an enforcement action; without such “incentives,” the police often won’t act.

The real question of course isn’t whether change comes, but whether it comes fast enough. Chimpanzee populations are difficult to tally with confidence, but some studies show alarming declines in some places. As recently as 60 years ago, experts believe several million chimps – covering as many as 14 different sub-species – lived in a band across Africa from Gambia to Uganda. Today, an estimated Africa-wide, 100,000 to 200,000 chimps (and four subspecies) remain in the wild. The decline may even be accelerating. Last October, for instance, researchers reported a decline in the chimpanzee population in Ivory Coast of 90 percent in less to 20 years, to a mere 1,200. In Gabon and Congo, the two countries home to the largest populations, numbers are believed to be declining by 5 percent a year.

With alarming trends, conservation measures remain urgent, and the preservation of Africa’s chimps and its forests must co-evolve. Efforts to save one will reinforce the health of the other. Dr. Speede is a long-term player in this faraway drama. “I’ll never walk away from this challenge,” she says.

Read author G. Pascal Zachary’s introduction to this excerpt.