The 20th century saw the rise of a new threat to public health that quickly grew to claim tens of thousands of lives every year in the United States. The cause? Automobile accidents.

Of course, many of those deaths were preventable. The seat belt was patented in 1885. In the 1930s, physicians horrified by the carnage urged automobile makers to add them as standard safety equipment.

But it wasn’t until Volvo safety engineer Nils Bohlin’s three-point safety belt was patented in 1959 that the tide began to turn. Over the next decade, the American Medical Association and the American Safety Belt Institute pushed for stronger vehicle safety laws. State governments passed laws mandating front-seat lap belts. The National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 required that new cars have three-point belts, front seat and back.

But putting seat belts in cars and getting people to use them turned out to be separate problems. With just 15 percent of drivers and passengers using seat belts in the late 1960s, annual deaths passed 50,000. This prompted the Ad Council’s public service campaigns imploring people to “buckle up for safety.” Under continued pressure from nonprofit organizations like the National Safety Council, state legislators passed laws requiring seat belt usage. Today, 85 percent of Americans buckle up and fatalities have fallen from more than 5 deaths per million miles in 1959 to just about 1 per million miles today.

The Importance of Multisector Social Innovation

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

The three-point safety belt is one of the most successful and effective social innovations ever developed. A low-cost, relatively simple technology, millions of people use it, and it saves tens of thousands of lives every year. But it took decades to turn Bohlin’s invention into a solution that has a broad and significant impact on people’s lives.

Why? Because no invention or idea—no matter how brilliant, no matter how many deaths it promises to prevent—ever achieves the scale necessary to sustain positive impact on the large numbers of people without drawing on expertise and resources from across the public, private, and social sectors.

And how the three sectors work together is critical. Success ultimately depends on whether organizations can draw on a wide portfolio of collaborative models to work together in different combinations through different types of relationships and engagements that shift to fit specific goals.

Most Americans use their seat belts today thanks to a series of shifting partnerships among various combinations of private-sector manufacturers, public-sector policymakers, and social-sector organizations. Advocacy organizations worked with state legislators to pass laws requiring the installation of seat belts as standard safety equipment. This created a market big enough to ramp up manufacturing—as more state laws made seat belts mandatory in the early 1960s, the number of seat belt manufacturers grew from 8 to more than 80. The growing market also justified investments to develop innovations like locking retractors that make seat belts more comfortable and provide more protection in a crash. Ad campaigns created by the nonprofit Ad Council working with the US Department of Transportation, funded in part by carmakers, and with television commercial time donated by for-profit broadcasters, persuaded people to buckle up in increasing numbers.

This is the essence of social innovation. In the case of the seat belt, this included the invention itself, the manufacturing capabilities provided by the auto industry, public policy crafted by federal and state government, and research and advocacy by academic institutions and nonprofits. The success of the seat belt wasn’t always the result of planned and purposeful partnership, but it took contributions from all three sectors.

This journey from invention to social innovation at scale offers important lessons for the present time. The demographic revolution of the past three decades has seen millions of people around the globe rise out of poverty and into the middle class. This, combined with the emergence of disruptive digital technologies such as mobile devices, big data, and genomics has created unprecedented opportunities for the public, private, and social sectors to work together to develop and deliver social innovations that can improve people’s lives at great scale. The opportunities for social innovation to play a significant role in addressing global health and development issues is reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals, which explicitly call for a larger role for the private sector in global development.

Picking the Right Engagement Model for Social Innovation

It’s easy to talk about the importance of multisector partnerships, but it’s quite another challenge to figure out how to forge and sustain successful relationships. For those of us working in the social sector (nonprofits, philanthropic organizations, and academic institutions), one of the most important questions we face is how we can work in partnership with companies and governments to quickly and efficiently discover, develop, and deliver social innovations at the scale needed to truly make a difference. It’s the central topic at international meetings, in business schools, and around conference tables where people gather to discuss and debate engagement models, funding approaches, and incentive structures.

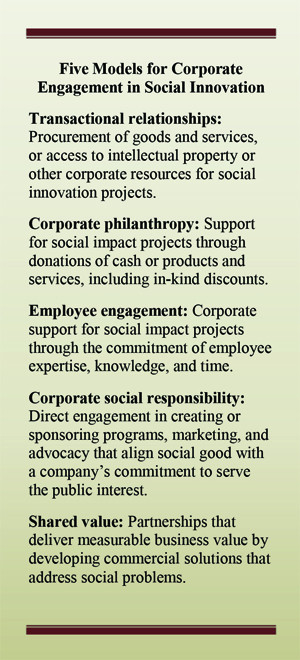

The ongoing debate about what makes for a successful multisector partnership reflects, in part, how the discipline and practice of social innovation has evolved and matured. The range of models for partnerships between the social and corporate sectors has grown considerably in recent years and now includes transactional support, corporate philanthropy, employee engagement, corporate social responsibility, and shared value (see sidebar).

Plenty of multisector partnerships have achieved admirable results, including the work the global vaccine organization Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and UPS have done to improve access to vaccines in remote areas. Live Well is a social enterprise established through a shared value partnership between Barclays, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), and CARE to raise awareness of health issues. The partnership has improved access to a wide range of health care products in Zambia, sold more than 122,000 health products, and reached nearly 700,000 people. And in sub-Saharan Africa, the Meningitis Vaccine Project—a partnership between PATH (the global health nonprofit that I lead), the World Health Organization, the Indian vaccine manufacturer Serum Institute of India, and several US government agencies—led to the development of a low-cost vaccine that has nearly eliminated meningitis in the region.

But the discussion and debate also reflect uncertainty about what works, what doesn’t, and how to determine which partnership approach offers the best opportunity for success. At the moment, notable successes are more the exception than the rule. According to a recent analysis of more than 1,400 public-private partnerships supported by the US Agency for International Development, fewer than 10 percent lasted as long as five years. The study also found that the number of new partnerships has fallen over the past few years, despite increasing focus on multisector partnerships in global development.

In general, even successful multisector partnerships are often short-term, one-time engagements that are more transactional than strategic. They are usually focused on a single project rather than on developing long-term strategic relationships that are flexible enough to span different projects, and dynamic enough to address the range of challenges that arise between great idea and life-changing solution at scale. They also tend not to deepen over time as partners leverage the advantages that come from learning more about each other’s capabilities, skills, and expertise.

Challenging the Hierarchy of Corporate Engagement Models

There are many reasons why multisector partnerships flounder. It is inherently challenging to bring together organizations that have different long-term objectives, respond to different incentives, measure success and understand risk differently, speak different organizational languages, and fund projects from different kinds of sources.

The high failure rate and preponderance of one-off, short-term projects is exacerbated by the fact that both the corporate and social sectors tend to understand social innovation approaches as discrete models they can adopt wholesale and use to the exclusion of other approaches or combinations of approaches.

Both sectors also often assume there is a hierarchy of social innovation approaches—a natural progression from least advanced to most evolved Although this kind of thinking lends itself to provocative panel discussion titles like “Is Corporate Philanthropy Dead?” at conferences and convenings where consultants, academics, and practitioners gather to promote their favorite theories, it is mistaken. It overlooks the fact that each one of these models is a legitimate and useful tool that can deliver positive results when applied in the right context to the right challenge. There are times when access to technology provided through a corporate discount or an infusion of funding made possible through corporate philanthropy is the best way to improve lives. And as intriguing—and promising—as shared value can be, a market-based solution cannot adequately address all problems; sometimes affected communities are too poor and the markets too underdeveloped to provide the incentives needed to generate a profit for a private-sector provider.

Portfolio Management to Create Dynamic Multisector Relationships

All of this suggests a need to fundamentally rethink how the private and social sectors engage with one another. Transforming an idea into a product or service that improves lives at scale is a complex process. It starts with a potential solution for an unsolved challenge that accounts for technical feasibility, the regulatory and policy environment, economic viability, and market sustainability. The end result must be appropriate, available, accessible, and affordable to those who need it.

The best—and probably the only—way to do this on an ongoing basis is to move beyond today’s focus on applying a single model to a specific project, and instead think about how social- and private-sector partners can create relationships that are flexible enough to respond to challenges as they arise and that can span different projects as partners discover new ways to apply their resources to achieve shared goals.

This will require social- and private-sector organizations to think more in terms of portfolio management models—an approach that provides a dynamic framework for using the right tools at different phases of the product lifecycle and responding to different risk profiles.

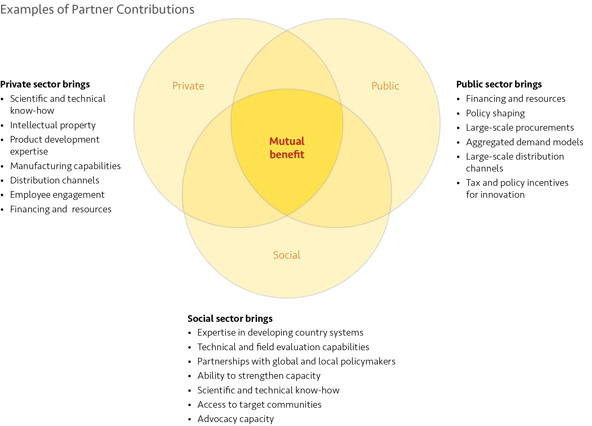

A portfolio approach to managing social innovation must be built to take advantage of the resources partners from each sector can offer as they are needed. These contributions will vary depending on the social issue the partnership aims to address and on local conditions. For example, in the world of global health social innovation, resources might include scientific and intellectual property, manufacturing capabilities, capital investment capacity, market development experience, distribution channels, and the human capital and expertise the private sector can provide. Governments play a critical role in mitigating risk and providing incentives to the private sector to invest in developing products and services for low-income countries and individuals by aggregating demand. The social sector brings an understanding of health challenges and an ability to identify potential solutions based on user, country, and market needs, along with technical and field evaluation capabilities, and scientific and technical know-how that can strengthen capacity and connect public health needs to private-sector capabilities.

None of this is easy. It requires that each partner gain executive support, invest time and effort to work across multiple divisions in partner organizations, create a flexible governance framework, and designate a relationship manager—or even a team—to coordinate within and across organizations so that different groups can engage where appropriate. It also requires the flexibility to redefine engagements dynamically—even if it means shutting down a specific project—without the risk of harming the overall relationship. And it should be designed to help manage risk so that the relationship doesn’t rest on the success of a single project or one model.

PATH’s Corporate Engagement Portfolio Model

Even at PATH, where we have been working with partners from all three sectors for 40 years, this portfolio approach is a new way of thinking about how we pursue social innovation. For example, we have worked with the global pharmaceutical company GSK for many years on a range of scientific initiatives and product-development efforts aimed at addressing health issues in low-resource communities. These efforts have included a partnership to develop the first malaria vaccine ever to receive a positive scientific opinion from the European Medicines Agency.

Yet both organizations recognized we weren’t achieving the level of impact that should have been possible given the breadth and depth of our collective resources. We determined that the transactional nature of our efforts, with each project taking place in its own narrow silo, was holding us back. In 2016, we looked more strategically and broadly across our respective portfolios—including market access, product development, and vaccines and medicines—and identified a number of promising collaborative initiatives. We then narrowed them down to a manageable set of projects tightly aligned with our organizations’ goals and resources. Next, we set up an oversight committee that included strategic leaders from multiple departments in both organizations and agreed to a memorandum of understanding that clearly defined each organization’s roles and responsibilities.

By taking a much more systematic and dynamic approach to identifying promising opportunities, we have the option to utilize all of the models for corporate engagement in social innovation in different combinations, depending on the needs of a given project. We are moving forward with new initiatives focused on child and maternal health, malaria prevention and treatment, and improved access to vaccines, drugs, and devices—all supported by more deliberate employee alignment and advocacy engagements.

In our work with corporate partners, we’ve found that the amount of time it takes to define and coordinate a relationship and drive an engagement to the point where it is delivering tangible results raises concerns about opportunity costs for both sides’ technical and business teams. Success depends on our ability to engage the right corporate leaders and employees, ensure the support and engagement of the board of directors, and develop the right governance models. And across the public, private, and social sectors, we all have a lot of work to do to better understand each other’s language, culture, motivations, and incentives. But there’s no doubt that multisector partnerships offer a smart and sustainable model for delivering social innovations that significantly improve global health outcomes.

It took more than 100 years for seat belts to go from promising invention to social innovation that saves tens of thousands of lives every year. To have any hope of achieving the targets set forth in the Sustainable Development Goals, we’ll need to turn great ideas into solutions that are affordable and accessible for billions of people—not in a few decades, but in a few years. Learning how to better manage diverse, complex, and dynamic multisector partnerships will be essential to achieving this.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Elaine Gibbons & Steve Davis.