(Illustration by James Heimer)

(Illustration by James Heimer)

On January 27, 2017, President Donald Trump signed an executive order banning the citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States. The broad language of the decree included those with valid visas, refugees who had been cleared for entry, and even green card holders. The ACLU was at the ready with legal arguments against such a move and, together with its allies, immediately mobilized a challenge. Meanwhile, thousands of Americans flocked to major airports across the country to protest the ban and to demand the release of hundreds of detained travelers.

One day after the ban went into effect, a federal judge granted the ACLU’s request for an emergency hearing, blocking the deportations and ordering customs officials to provide a list of individuals who had been detained as a result of the ban. It was the first successful challenge of a Trump executive order and the fulfillment of a promise the ACLU made two days after Trump was elected: “We’ll see you in court.”

As expected, during his first month in office, Trump wasted no time implementing an unconstitutional agenda to undo many of the civil liberties gains of the past quarter century—from immigrants’ rights to reproductive freedom to LGBT rights. His actions validated an unprecedented outpouring of support following his election for the ACLU and its nonpartisan mission to defend civil liberties and uphold the US Constitution and the Bill of Rights in every town, city, and state in America. Since Trump was elected, our membership has quadrupled to 1.6 million, and our activist alert e-mail list is 2.2 million and growing. Trump’s travel ban alone provoked a record fundraising haul of $24 million from 356,000 online donations.

While we cannot claim to have predicted—or frankly even imagined—a Trump presidency, we came on board more than 15 years ago knowing that the ACLU needed a plan for smart and strategic growth in order to confront the inevitable civil liberties crises ahead. Within the first week of Trump’s inauguration, we had one, and we were prepared.

This is the story of an experiment that came to be known as the ACLU’s Strategic Affiliate Initiative (SAI)—an ambitious $39 million investment in 11 key states over 10 years—which readied the organization for the Trump years. The numerous battles both fought and anticipated will determine whether the United States remains a country where people’s rights and freedoms remain inviolate.

An Unequal Equilibrium

The ACLU was founded nearly 100 years ago during another national crisis. In the years following World War I, America was gripped by the fear that the Russian Revolution would spread to the United States. In November 1919 and January 1920, in what became known as the “Palmer Raids,” US Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer began rounding up and deporting so-called radicals. Thousands, including some US citizens, were arrested without warrants and brutally treated—and more than 500 foreigners were deported for suspected political leanings and activism. In the face of these egregious civil liberties abuses, a small group of lawyers and activists decided to take a stand, and the America Civil Liberties Union was born.

From the ACLU’s inception, its leaders understood that civil liberties were something that must be delivered locally.

Over the years, the ACLU has evolved from a small group of idealists into the nation’s premier defender of constitutional rights. Today we continue to fight government abuse and defend individual freedoms, including speech and religion, a woman’s right to choose, the right to due process, citizens’ rights to privacy, and much more. We stand for these rights even when the cause is unpopular, and sometimes when nobody else will, for it is during times of popular fervor that civil liberties are most at risk. While not in agreement with us on every issue, Americans have come to count on the ACLU for its unyielding dedication to principle.

From the ACLU’s inception, its leaders understood that civil liberties were something that must be delivered locally. As the organization approached its first decade in 1929, founder Roger Baldwin issued a call to action: “The time has come to decentralize our work; to build up local organizations all over the country.”

Unique among social justice and advocacy organizations, the ACLU today has affiliates in every state, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. They are the vehicles through which we obtain clients for our cases and achieve legal victories. Affiliates’ relationships with state and local officials give us leverage in the political arena and provide the means for local organizing. They also serve as the flash points where many civil liberties battles are first fought and opportunities are revealed.

Since our affiliates were born in what was essentially a free market, a state’s political climate and aggregate wealth often set an upper limit on an affiliate’s growth. Each office grew at an organic rate toward an equilibrium point, in which its capacity equaled the fundraising level within the specific affiliate. Within this dynamic we saw an opportunity: If the level of funding was raised, we could raise the level of activity.

The seeds of this theory began germinating even before (co-author) Anthony Romero officially took the helm of the ACLU on September 4, 2001—seven days before 9/11. Before he accepted the position, he embarked on a series of consultations with a broad range of people inside and outside the organization, in the United States and abroad, including many ACLU affiliates. He began his tenure with a plan for growth that predated the events of 9/11. In their wake, the plan became even more urgent. A key element of this vision was to grow affiliates across the nation. The effort started with the creation of a new entity within the organization, the Affiliate Support Department (ASD), and a new leader, (co-author) Geri Rozanski, who came on board in 2002. ASD would partner with affiliates to grow not only legal, legislative, and public education programs, but also fundraising and operational capacity that would enable affiliates to reach a new equilibrium.

Understanding the Affiliates

Prior to the establishment of the ASD 15 years ago, there was no national ACLU staff member whose full-time responsibility was to provide affiliates with technical support or guidance. The lofty ideal that “every national staff member has a responsibility to assist the affiliates” meant that, too often, no one took responsibility until a problem—typically financial—became a crisis.

Since the ACLU’s founding, its affiliates have been stand-alone organizations with their own staff and board of directors. A national board, with representatives from the affiliates, determines program policy. The national ACLU’s fiscal responsibility to affiliates is discharged largely through a sharing formula whereby donations solicited by the national development department are shared with the affiliate of the donor’s home state, and likewise, a percentage of funds raised by an affiliate are shared with the national office. Initially, an annual subsidized “guaranteed minimum income,” approximately $75,000 prior to the launch of SAI, was provided to each of the 25 affiliates with the smallest membership, known as “GMI” affiliates.

Affiliates in states less sympathetic to civil liberties, such as Mississippi, often had the lowest membership and therefore the smallest amount of financial support.

A key difference in the SAI structure is that it was funded largely by individual donors in non-SAI states, such as New York and California, who recognized the strategic need to build support for civil liberties in states such as Texas, Mississippi, and Florida. Affiliates and donors alike understood the need to bypass the usual sharing formula for this initiative.

To implement our ambitious plan for growth, we began by analyzing the highest-capacity affiliates to understand the how and why of their success. It came as no surprise that coastal states such as New York and California had access to a much deeper potential investment pool. Not only is wealth in the United States concentrated on its shores, but potential donors in these parts of the country, we found, were much more sympathetic to the ACLU’s causes.

It was also unsurprising that affiliates in states less sympathetic to civil liberties, such as Mississippi, often had the lowest membership and therefore the smallest amount of financial support. In addition, many of the affiliates, even in larger states such as Texas, were essentially skeleton organizations made up of an executive director and a few dedicated support staff, relying on help from local volunteers as well as a national legal staff who were already stretched thin. Affiliate executive directors responsible for large geographic areas such as Montana, Florida, and Michigan faced similar challenges of scope on a daily basis.

Our analysis confirmed the belief that a special investment in key affiliates could have an enormous impact on civil liberties throughout the nation. Such an effort could build momentum for change at the grassroots level while simultaneously unifying and strengthening the ACLU as a nationwide organization.

Finding the Right Criteria

We next needed to formulate a strategy. To figure out how to proceed, we devised clear internal and external criteria to identify those states in which we could accomplish the greatest increase in social impact through the infusion of resources.

Externally, we were looking for states where the population was shifting and growing, where there was a disproportionately high number of racial minorities and people below the poverty level—populations historically most vulnerable to civil liberties violations. We also sought to identify those states in which the number and severity of civil liberties violations surpassed the affiliate’s capacity to respond. Finally, we reviewed each state to determine whether other nonprofits were filling the gaps with robust legal and advocacy programs. Our intention was to add value, not to replicate the work of others.

The internal selection criteria included whether an affiliate was willing and able to assess their own strengths and weaknesses and work in close collaboration with the national office for a decade or more. To clarify our expectations for the partnership, we established five essential qualities that affiliates needed to be successful: accountable, disciplined, ambitious, collaborative, and strategic. Accountability was probably the most important quality, given our reporting obligation to many individual donors as well as to foundations. Discipline was also key: Affiliates would need to commit to doing things differently and be prepared to follow through over the long term.

As for being ambitious, collaborative, and strategic, we gauged these qualities by asking affiliates how their portfolios (legal, legislative, communications, and development) would benefit from enhanced capacity. Staff attorneys working on national projects were also interviewed, as were organizers working in the national legislative office. We also had the benefit of ASD’s early experiences in distributing micro-investments to affiliates, which provided insight into how different affiliates managed the resources they had, as well as their ability to think strategically about goals and objectives.

Finally, we sought out states where the national office could test out new models for program development and implementation—such as the establishment of a Regional Border Office in New Mexico to address civil and human rights violations against immigrants in southwestern states, including Texas, Arizona, and California.

After we analyzed all the data, we identified five affiliates for the first wave of SAI funding in 2006: Florida, Mississippi, Montana, New Mexico, and Texas. The program eventually grew to include six more affiliates: Michigan, Missouri, Tennessee, Arizona, Colorado, and Southern California. Although the last affiliate is well-funded and in a largely progressive state, we added the region specifically to experiment with opening an office in the Inland Empire east of Los Angeles to reach underserved immigrant communities. (California comprises three separate affiliates: the ACLU of Southern California, the ACLU of Northern California, and the ACLU of San Diego and Imperial Counties, but for purposes of statewide advocacy and initiatives, they are identified as the ACLU of California.)

Business Planning

Like many nonprofits, these SAI affiliates had ambitious program goals but were not always guided by realistic projections of financial activity or resource constraints. Few if any had sophisticated financial accounting systems in place, and the program planning of even the better-resourced affiliates could easily be derailed by a high-profile crisis.

Our first step, therefore, was to introduce business planning into each affiliate’s regular operations. A key player at this stage—and throughout the entire SAI process—was Aviv Aviad, a consultant who has provided financial and analytical services to the nonprofit sector for decades. With degrees in law and economics, Aviad was uniquely qualified to understand and address the skills gaps within the affiliates, particularly with regard to finance. After initially acting as a consultant, he became director of the SAI.

As we prepared to put in place the most ambitious investment ever undertaken by the ACLU, we had to establish transparent mechanisms to keep stakeholders on track.

“Our theory was that building up capacity and infrastructure would ultimately make the affiliate more attractive for local donors and thus help sustain a higher level of equilibrium,” Aviad says. “You build all this capacity so affiliates can raise more and do more.”

To implement this revitalization project, Rozanski and Aviad chose what we call a “foundation-plus” model, combining the grantmaking structure of a foundation with the “plus” of intensive collaboration with our affiliate “grantees.” By the start of the SAI planning process in 2004, Rozanski and her staff had established close working relationships with all of the affiliates and had already seen the positive effects of strategic investments. In addition to raising the yearly subsidy for the 25 smallest GMI affiliates from $75,000 to $115,000, ASD provided $2.5 million in grants to states such as Texas and Mississippi, as well as close to $1 million in support of the ACLU’s post-9/11 “Keep America Safe and Free” national campaign. Notably, this support included $850,000 to fund staff attorneys in 17 affiliates where there had previously been none.

These initial grants infused our affiliates with new life and brought significant and dramatic improvements. For instance, by 2005, within three years of receiving this support, the ACLU of Texas tripled its operating budget and saw its constituency double to more than 15,000 active members. The success of these efforts validated our concept for the SAI.

In 2005, Aviad came on board full-time to work with Rozanski on implementing the SAI program. They started by asking the first group of five SAI affiliates: If you were building your organization from scratch tomorrow, what would it look like? We challenged them to think about what they needed to start afresh, with the goal of going on the offensive instead of just playing defense against bad civil liberties laws and proposals. The answers guided them in creating an organizational structure that would enable the affiliates to accomplish their policy priorities.

A financial model was then developed, taking into account the affiliate’s fundraising potential, followed by a business plan to reflect the growth plan and financial projections of the affiliate. Adaptability was key: Each affiliate’s business plan was updated at least every two to three years in order to revisit assumptions, reflect changing circumstances, and address barriers to success.

Every business plan included three key measurements that served as a barometer for success over the course of the investment:

- Growth in membership, indicating an increase in general popular support.

- Increase in the number of mentions in the media, indicating high relevancy to top-priority issues.

- Growth in fundraising income, indicating donors’ belief in an affiliate’s ability to make an impact.

To formalize the agreement, the national office and the affiliate signed a memorandum of understanding defining the expectations and terms of the SAI plan—namely, the affiliate’s commitment to work toward the completion of its policy agenda and the national ACLU’s commitment to fund the affiliate’s growth based on the business plan.

Funding and Reporting

As we prepared to put in place the most ambitious investment ever undertaken by the ACLU, we knew we had to establish several transparent mechanisms to keep all stakeholders informed and on track. First, we needed budgeting processes that ensured accountability. Second, we needed a quantitative and qualitative reporting structure that would demonstrate the value added by the program and allow for recalibrations along the way. Third, we needed a way of demonstrating to our donors and stakeholders, and to the affiliates themselves, the impact of the new, disciplined approach.

SAI budget requests became a cornerstone of the program, enabling affiliates and the national office to communicate clearly about expenses. Every fiscal quarter, affiliates submitted a request for the succeeding quarter. These requests were designed to enable the national office to review a detailed, line-by-line breakdown of its quarterly grants. Moreover, by asking affiliates to submit requests in the quarter prior to expenditures, we sought to alleviate any cash flow concerns for those affiliates with lower levels of reserves. We viewed the budget requests as a mechanism to ensure that the financial allocation was always linked back to an affiliate’s business plan and that money was channeled toward the program’s carefully outlined initiatives in each state, such as the hiring of a specific position or the opening or expansion of a new office.

While each affiliate’s first year in the program began with 100 percent funding of SAI initiatives, we established a subsidy rate system that would gradually decrease national’s funding each fiscal year until an affiliate was fully able to sustain its own growth. (See “Subsidizing Affiliates.”)

An affiliate “graduates” when funding is completely disbursed—usually after a period of seven or eight years. By this point, affiliates have consistently met their detailed set of program, financial, and leadership goals, and are clearly able to sustain a higher level of functioning absent the SAI investment. All SAI affiliates, except Mississippi, have graduated. (Through the national office’s grants program, we will continue to subsidize the critical work that cannot be sustained in Mississippi due to the limited pool of donors in the state.)

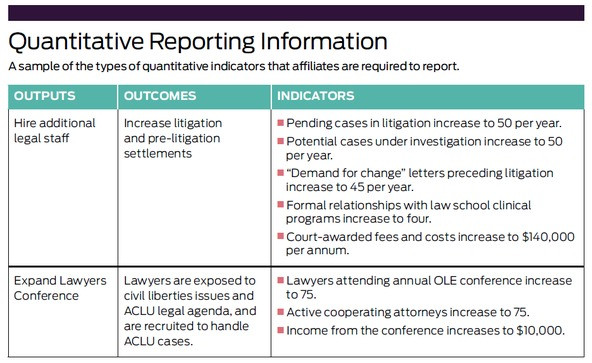

We also needed to create transparent reporting structures consisting of quantitative and qualitative information. The quantitative indicators include a mix of operational and programmatic benchmarks, such as the number of new cases filed, appearances before legislative bodies, donations, and television and radio interviews. (See “Quantitative Reporting Information.”)

In addition, we asked affiliates to provide a qualitative assessment of their activities every quarter, including organizational and personnel changes as well as updates from the legal, communications, and legislative departments. Annual reports also included a bigger-picture reflection on policy priorities as well as barriers to SAI implementation and other challenges.

These reports were a helpful tool not just for the ACLU’s national office but for two other audiences. First, our funders (especially the Sandler Foundation) appreciated the high level of accountability and first-hand information about affiliate activities. Second, the affiliates’ boards began to use these reports for their fiduciary and organizational oversight responsibilities. This governing tool enhanced the internal accountability of the affiliates to their board and helped boards to be more strategic in decision making. Our SAI graduates continue to provide such updates to their boards, and many of the non-SAI affiliates have also adopted the reporting system.

In addition to quarterly check-ins, ongoing assistance from Affiliate Support is an integral part of the SAI experience. Both Aviad and Rozanski either spoke or met with the affiliates’ management teams at least twice a month to remain informed about challenges and issues, provide advice, and adjust the business plan based on changing circumstances. Virtually every affiliate found the need for some adjustment along the way. For instance, the New Mexico affiliate realized that instead of opening a Santa Fe office as planned, they could accomplish their goals and eliminate overhead by having a lobbyist commute the 60 miles from Albuquerque.

The Dividends of Collaboration

By the time the national ACLU had established a department to work directly with its affiliates, many of them had been in operation for more than 50 years, but with only marginal growth to show for it. Rozanski reviewed more than one organizational chart that had not changed in more than a decade. Not surprisingly, the same was true for funding levels in all but the most progressive states.

The SAI experiment demonstrated that strategic investments could not only secure more staff but also deliver greater impact. The growth in membership at the ACLU of New Mexico, for example, was due not to the hiring of a membership specialist but to the addition of legal, policy, and communications staff that boosted the organization’s effectiveness and public profile, which in turn attracted clients, donors, members, and even job seekers as the organization’s prestige increased. As a result, the ACLU of New Mexico no longer receives a GMI subsidy. The ACLU of Missouri is another affiliate that is now categorized as midlevel due to sizable increases in membership and funding.

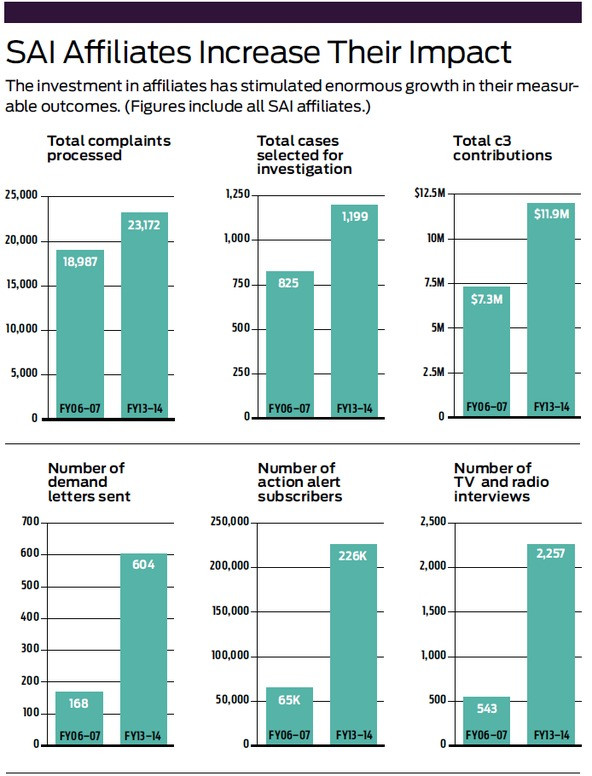

Over the last 10 years, SAI investment in affiliates has stimulated enormous growth in virtually all areas that we measure, such as complaints processed, financial contributions, and TV and radio interviews. (See “SAI Affiliates Increase Their Impact.”) The 11 SAI affiliates now collectively boast nearly 200 new staff members, an increase of 53 percent over their pre-SAI sizes.

But enhanced capacity is more than just the number of people hired or cases filed or even funds raised. It is also realized in the quality, balance, and effectiveness of the program. SAI affiliates now leverage their combined strengths in litigation, communications, and advocacy to amplify the issues. These affiliates also now have robust development and administrative teams to ensure that their programs are sustainable and effective.

The SAI has given participating affiliates the courage to abandon what has not worked well in the past, along with the tools to face the future with confidence, knowing they have SAI as a safety net. “SAI empowered me to be as bold and creative as I wanted to be,” says Kary Moss, ACLU of Michigan executive director. For instance, she hired an investigative journalist to delve into the state’s controversial Emergency Manager Law, a move that ultimately led to the exposure of the Flint water crisis. Several other affiliates are now seeking to hire such investigators.

Additionally, enhancements in organizational capacity and leadership skills at the 11 affiliates make them more appealing both to foundations and to individual donors, which is a promising sign for future sustainability. The ACLU of Michigan, for example, explicitly seized on its SAI participation as a marketing tool for fundraising. “When I was able to go to donors and say our national office picked us to invest in because Michigan is so important to the national landscape, people were on board to help us sustain our goals,” Moss says. The affiliate’s 2008 fundraising campaign goal of $6 million was exceeded by $2 million over four years with the spur of the SAI investment.

Another impact from SAI’s success—one that we explicitly anticipated—was the synergy created by collaboration among the 11 affiliates, and their resulting influence on non-SAI affiliates’ approach to their work. All of the SAI tools have been made available on our internal website, and from the beginning we shared the SAI experiences at annual and regional conferences. Many non-SAI executive directors are now using SAI organizational charts and business plans, and three non-SAI affiliates—Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Georgia—have implemented business plans directly modeled after the program. In general, we notice that all affiliate leaders are thinking more strategically and more ambitiously about what they can achieve in their states by developing more sophisticated strategies to integrate litigation, public education, and advocacy programs to advance their priorities.

Overall, the SAI has inspired a new collaborative culture across all affiliates. For example, 15 ACLU affiliates, including seven SAI participants, ran phone banks in 2013 to help defeat Albuquerque’s ballot initiative to ban abortion, which would have been the first such ban in the nation. Working collaboratively and thinking nationwide is now the standard by which national and affiliate staff approach work.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

More than 10 years after SAI’s launch, we have learned many important lessons. Knowing that a business plan could not be a one-size-fits-all template, we were able to get the most out of our investment in each affiliate by being highly adaptable to the particular circumstances of each one. This flexibility included helping managers transition into new roles, making quick adjustments to emerging problems from quick growth, and being smart about how to staff and how to acquire and retain talent.

As affiliates grew and created more elaborate systems for their operations, many longtime executive directors suddenly saw a seismic shift in their day-to-day work. We found it useful to coach executive directors through this transformation in role, as they homed in on a new skill set to best serve their growing organization.

The SAI investment “freed me up to do what I do best—get out of the weeds and really focus on external relations,” says Moss, who hired a deputy director as well as six other staff by the second year of the SAI. That meant creating a leadership team instead of hearing direct reports from six or seven individuals on her senior staff. It was a year before people came to embrace team meetings and group decision making. In retrospect, she would have invested more time up front on professional training for her staff in supervision and other areas: “how to give feedback, how to hold people accountable, how to create performance improvement plans.”

Similarly, ACLU of Florida Executive Director Howard Simon enjoyed the “shot in the arm” that allowed his affiliate to continue on a path of expansion it had already begun in 2005, opening branches in Orlando and Pensacola. The addition of a deputy director gave him more time to drive across the state to meet with donors. But in the beginning he struggled with no longer being the face of the ACLU in cases where messages were nuanced. He adapted by first acting as a sort of messaging manager with his legal and communications staff, a role he gradually ceded as the communications team demonstrated their ability to handle external relations and as the legal team increasingly saw the value in smart and accessible messaging.

The early years of the SAI taught us that growing too fast—for the affiliates and for the SAI program as a whole—can have negative consequences. “The ACLU feels comfortable hiring lawyers—it’s what we’re good at,” says Alessandra Soler, ACLU of Arizona executive director. But, she cautions, “don’t hire for your program until you have your development people on board.” Once Soler hired her first-ever development director—and that director secured the affiliate’s firstever six-figure gift—the program took off, just in time for the affiliate to confront the challenges of Arizona’s new anti-immigrant laws.

In Texas, Executive Director Terri Burke weighed the need to expand work on the border with her desire to establish a presence in Dallas. Ultimately, she decided that she could not do both effectively and shelved the Dallas plan, focusing instead on her affiliate’s coordination with the newly established Regional Office for Border Rights (ROBR) in New Mexico. The ACLU is now planning on moving the ROBR to El Paso, as border incidents have shifted from New Mexico to Texas, and the ACLU of Texas has grown sufficiently to manage the organizing and outreach work that is necessary.

Heeding these early lessons, we learned to adjust business plans to facilitate slower, more organic growth. Notably, we realized that our estimate of a five-year investment period did not provide enough time for all SAI affiliates to build their development programs and achieve sustainability. We ultimately determined that seven to eight years was a more realistic timeline. In doing so, we also decided to invest more resources in each affiliate and as a result limited our second round of investment to six affiliates, for a total of 11.

Managing the rate of growth, we found, also allowed affiliates to better control recruitment processes, secure sufficient infrastructures to support growth, and reduce confusion due to changes in staffing roles and responsibilities.

While most affiliate directors were familiar with hiring legal staff or at least working with volunteer lawyers, some were building development, communications, and policy teams for the first time. In particular, as SAI affiliates sought to add or expand development staff, they found that the pool of skilled nonprofit development professionals in their states was limited and the ACLU could not compete with large nonprofits, such as universities, in terms of salary or career opportunities. In addition, candidates who were high achievers were often reluctant to operate as a one-person shop, while those in the earlier stages of their careers were sometimes challenged by transitions as the program grew.

We also found that development professionals from other institutional backgrounds are not always well grounded in the ACLU donor culture, which is based on one-on-one solicitations with individuals who are passionate about the ACLU’s mission and invested in the particulars of the work. (Also, unlike other nonprofits, the nonpartisan ACLU does not accept government funds and does not rely on corporations or events as fundraising tools.)

The affiliates have met these challenges in two ways. First, they have continued to be ambitious: The more numerous and high-profile the affiliates’ achievements are, the more attractive they become to the best professionals in all categories. Second, they looked within their own organizations to find the right person for the job. For example, the ACLU of Michigan’s deputy director moved into the role of director of development after a colleague’s departure, upon which the communications director became the new deputy director. Such moves allow staff to gain new skills while keeping institutional experience in-house. “You don’t need to know how to use a database,” says Moss, “but you do need to have the ACLU in your DNA.”

The ACLU of Texas followed the same logic when it promoted existing staff to open positions on its policy and advocacy team. There also continues to be movement of staff between affiliates. For example, the ACLU of Southern California’s new director of philanthropy came from the ACLU of New Mexico. Familiar with both ACLU issues and the SAI program, she hit the ground running.

Strategic growth does not necessarily mean “bulking up,” and not every organization requires the same amount or type of investment for the same payoff. Depending on sustainability, organizational capacity, and the political environment, we found that modest investments in some areas could yield terrific outcomes for civil liberties, while providing benefits to the entire organization. For instance, in Tennessee, the addition of an administrative professional along with staff training allowed the affiliate to accomplish far more than it had previously—and much more than if it had just added more lawyers. Its improved program contributed to the affiliate’s ability to attract outside funding for a racial justice organizer, a key factor in advancing their priority issue of racial justice.

Sharing Our Knowledge

We believe that any national organization with state chapters or member networks, whether formal or informal, large or small—and even those without networks—can benefit from the lessons we have learned about organizational growth and leadership. In fact, at the request of one of our largest SAI funders, the Sandler Foundation, we shared our knowledge with another of their grantees, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP)—a widely respected research and policy institute—which was seeking to strengthen its network of state-based organizations.

Over the course of several years, CBPP’s senior vice president for state fiscal policy, Nick Johnson, met with Rozanski to learn more about the SAI model and how he could apply it to their state network. As a result, Johnson put together his own SAI, the Strategic Development Program (SDP), and ultimately refashioned his state network into the State Priorities Partnership, which was recently lauded in these pages as “a critical resource for legislators, media outlets, and advocacy organizations.”

If there is one takeaway he can share, Johnson says, it is that getting management right early on reaps the greatest benefits. While acknowledging that nonprofits have “unique dynamics,” Johnson says that there is no reason they should be behind the corporate sector when it comes to cultivating strong management and leadership. “Don’t fund groups to try to win a specific battle,” he advises. “Invest in leadership to get the success you want.”

Neither the SAI nor CPBB’s Strategic Development Program would have been possible without the visionary $12 million investment of the Sandler Foundation, which has long been a champion of the principle that investing in nonprofit infrastructure can yield equal or greater impact than investing directly in policy initiatives. Their vision was recently recognized by the National Committee on Responsive Philanthropy, which bestowed the foundation with its 2016 Impact award. In accepting the award, the foundation stated: “If we had one wish, it would be for philanthropic funders to set aside more resources to invest in the long-term institutional capacity of organizations and far fewer resources on short-term projects or programs. The issues we all care about will not be ‘solved’ in two or three years, and even after short-term wins, these issues will reemerge in new and unexpected ways.”

The Way Ahead

When we first embarked upon the Strategic Affiliate Initiative in 2006, our goal was to build institutions that could meet future challenges successfully, including those not yet imaginable. The next phase in our evolution is “SAI 2.0,” building a base of support in key states that can mobilize our rapidly growing membership to help us win legislative battles at the state and federal levels.

Unlike the first program, SAI 2.0 will focus more on organizational transformation than on structural sustainability. Our plan is to invest in a blend of staff and professional services to advance state-level and nationally coordinated messaging, polling, and analytics fundamental to nonpartisan political wins. The first states to embark on this next phase are Florida, Georgia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas. We are currently seeking to invest in as many as 10 other states—representing red, blue, and purple voting patterns—in order to seize emerging opportunities and respond to the most pressing threats.

While the planning for SAI 2.0 was in place before Trump’s election, it has become even more urgent since. From rolling back LGBT rights to defunding Planned Parenthood to abandoning US Department of Justice oversight of police abuse, Trump’s policies have the potential to affect the lives of millions of Americans in heartbreaking ways.

“The stakes are so high right now,” Simon says. “There will be worse public policy proposals coming down the pike, proposals that undoubtedly will ripple across the policy-making process in other states. SAI 2.0 will provide the resources for us to take on these fights and win.”

As an executive director in an SAI 2.0 state, Simon is not waiting around for bad news. With the resources to go on the offense as well as fight defensively, he is already embarking on an ambitious criminal justice reform agenda, as well as leading a ballot initiative to restore voting rights to the approximately 1.6 million Floridians subject to a Jim Crow-era lifetime voting ban for former felons.

There is no question that the SAI program has reshaped the landscape of liberty in some of the most difficult regions of the country and raised the bar for what it means to be an ACLU affiliate. At the same time, it has enhanced the collective power and political clout of the national ACLU. Today, we face the constitutional threat of a Trump presidency knowing that we have the strongest ACLU in the nearly 100-year history of our organization. Long after he has left office, we will still be here, defending the rights and liberties of all.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Anthony D. Romero & Geri E. Rozanski.