A tiny fraction of the world’s 7,000 languages dominate the Internet. Participation in the digital world requires that users have a basic understanding of English, Chinese, Spanish, or one of several other languages commonly used for global communications.

And yet if local cultures are to survive and flourish, they still need their own languages. “It’s not enough to be able communicate,” a priest from the island of Bali once told me (in Indonesian, the national language) as he was preparing for a ceremony. “To really understand us,” he said as he tucked his cell phone into a pouch on his sarong, “you need to speak Balinese.”

The irony of the situation was not lost on the priest: He understood that the technology he carried in his sarong was accelerating the demise of his native tongue, and with it, the cultural identity of the Balinese people. But what he didn’t realize—and what the global language, cultural preservation, and linguist communities have now begun to appreciate—is that these same digital tools have the potential to revitalize local languages.

Technology on its own is not enough. If it were, then the space generously provided for local languages by Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Wikipedia, and others would be getting the job done. We’ve started to understand what else we need to keep local languages alive in the digital era, but it’s important to first grasp the stakes and the context in which the technology must work.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Today, as connectivity grows across countries and continents, linguists believe nearly half of the world’s languages will become extinct in the next century. Less than a quarter of all Balinese can speak their own language, and in North America, only 8 out of 165 indigenous languages are still spoken.

If the Balinese language were to disappear entirely, people in Bali could still communicate in the national language, Indonesian, or in English or other tongues. But the loss of Balinese, like any local language, would leave the island and the world a much poorer place. It would limit future generation’s understanding of the island’s unique culture, including its remarkable dance and music traditions, as well as the religious practices that guide daily life. It could also have economic consequences by undermining indigenous knowledge handed down over scores of generations—knowledge that, for example, governs the sustainable management of the island’s water resources for the equitable and productive growing of rice, the local staple crop.

Avoiding extinction means slowing and then reversing the decline of local languages. In turn, this requires an understanding that technology is just one element in the complex economic, political, cultural, and social system that favors majority languages at the expense of local ones.

Nationalism is also part of the picture. Many nations, especially newer countries, understandably want to promote a single language that unites their citizens. The United States, for example, initially banned the use of the Hawaiian language from local schools when Hawaii became a state. The goal was to get everyone to speak English, but the restrictions put the Hawaiian language in jeopardy. Local advocates eventually succeeded in getting the state to recognize the Hawaiian language, which paved the way for public immersion preschools and other programs that brought Hawaiian back from the brink.

Families exert further pressure. While many parents speak local languages to their children, others forgo their mother tongues in favor of English or Chinese or a handful of other international languages in an attempt to give their children more economic opportunities despite the many advantages of multilingualism.

Yet other forces against local languages come from within. The structure of some local languages, particularly those with a hierarchy based on social status (meaning that you use different words depending on the relative social status of the person you’re speaking with), can make younger speakers reluctant or even afraid to use the language for fear of offending. Younger speakers may also prefer a more democratic form of communication. Indeed, how can you apply status rules in the age of social media, when you can’t gauge the relative status of your audience?

Technology can help reduce the pressures on local languages and revitalize them in the modern world, but only if we apply it in conjunction with social, political, economic, and cultural measures to change behavior. Here are four guidelines based on my experience in Bali and other places where local languages are being supported, one byte at a time:

1. Engage local curators and motivators.

Once the Unicode—a digital font specific to a language’s own letters or characters—is available for a particular language, the Internet offers a relatively inexpensive way for communities to access local language materials. Universities around the world, the US Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Institution, and other repositories are increasingly digitizing their holdings of indigenous cultural material to provide access to local people. That process is time consuming and costly but it turns out that a bigger challenge is navigating the political, cultural, and ethical issues about whether and how indigenous materials should be shared online.

Jan Bender Shelter, a professor of history at Goshen College who has worked extensively with the Mara people of Tanzania, raised several questions on the prospect of digitizing indigenous materials: Who has authority to give permission to use indigenous materials? Are certain materials too sacred to be put online? To what extent can members of the Mara community understand, access, and navigate the digital collection? Would they find the material useful?

Addressing these questions—preferably before they become controversies—requires that a group of local scholars, artists, and community leaders all participate in the curation of digital materials. This group needs to have both expertise and legitimacy to develop materials that are accurate, appropriate, and readily accessible by the local community.

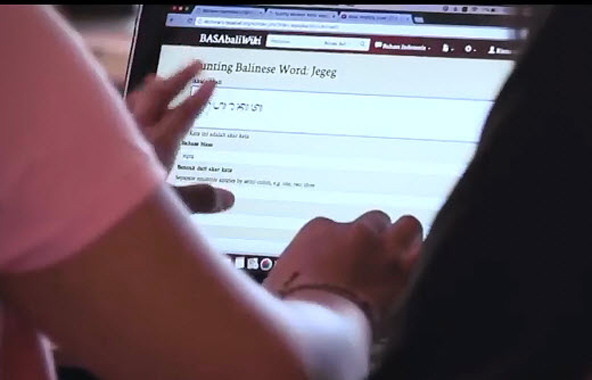

Government appointed "language ambassadors" adding modern uses of indigenous knowledge to the BASAbali Wiki. (Photo by Clara Listya Dewi)

Government appointed "language ambassadors" adding modern uses of indigenous knowledge to the BASAbali Wiki. (Photo by Clara Listya Dewi)

Equally important are local supporters who can encourage the community to embrace and participate in strengthening the local language on the ground and online. Poets, photographers, writers, composers, and others need to encourage people to get on board in whatever way their technology permits. Better to have the academics review entries posted enthusiastically than to scare people away.

In Bali, local curators and motivators are actively developing a digital cultural wiki, a multimedia combination of a dictionary and an encyclopedia that crowdsources, stores, and shares knowledge of the Balinese language and culture. At its most basic, the wiki functions as a “living” dictionary of words and phrases in Balinese, Indonesian, and English, some of which are illustrated with video clips. But it also serves as repository of modern and traditional literature, photography, music, and links to other cultural resources. The wiki is a powerful tool, but only because of the active motivation and curation by a diverse group of local experts, community leaders, and social media enthusiasts.

A teenager uses the BASAbali Wiki. (Photo by Ayu Mandala)

A teenager uses the BASAbali Wiki. (Photo by Ayu Mandala)

2. Reach into communities—and homes.

As with most social innovation, community participation is a critical component for long-term success. Community-run immersion schools for local languages have made inroads in strengthening Hawaiian and other local languages, as have local language radio programs in Central American communities. In Kenya, comic strips are getting teens and young adults to think and talk about issues of importance to them in Sheng, a local slang language that combines Swahili and English.

But succeeding also means influencing daily life at the household level. Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, one of the pioneers of the revitalization of modern Hebrew, recognized early on that for local languages to thrive, people need to use them consistently in the course of everyday life. The efforts to renew the use of Irish, Maori (the language of native New Zealanders), and other languages also benefited from programs for household participation. What happens in the home is important, because it affects where children learn to speak and value local languages, reinforced by their parents and grandparents. A language just taught in school or in a religious context risks becoming just a school or a religious language.

3. Value the local in the global.

“You care about Balinese?” people from Bali often ask me when they learn about my efforts to support their language. The question reflects a widespread belief that the vast majority of the world only values a few languages, which in turn discourages and undermines efforts to use local languages. But the flip side is also true: When the global community engages in initiatives to revitalize local languages, it provides encouragement and even legitimacy for local cultural advocates.

An international platform for local languages serves local needs and also demonstrates the value of those languages at the global level. Further, an international platform reminds others of the value of linguistic diversity and the cultural identity that comes along with it.

Perhaps Ward Cunningham, creator of the modern wiki, had an inkling that wikis would be one of the international platforms used to help local languages: He coined the technological term “wiki” after the word for “quick” in Hawaiian, a language which is under some of the same pressures as Balinese.

4. Don't wait.

UNESCO currently considers 2,500 languages endangered, which represents 35 percent of the world’s 7,000 tongues. Much of the global effort to maintain linguistic diversity is, understandably, focused on preserving these languages. But we should also be working to prevent languages from reaching the linguistic equivalent of an intensive care unit. The best way to do that is to start now with appropriate technological and community interventions to strengthen local languages. The sooner we get started, the more likely we’ll be to influence larger numbers of people to keep using, or to begin learning, their local languages.

Twitter, Google, and other high-tech ventures may be driven by market forces, but they are already intervening in this space, between the vulnerable and the safe, where there is still a solid base of speakers who may not be there in a generation. We need to follow their lead and get going now.

These four steps can help counter the marginalization of local languages, one of the unfortunate side effects of the Internet age. By reorienting digital tools in service of local languages, technology can instead become an enriching source of linguistic and cultural diversity.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Alissa J. Stern.