Husk Power Systems, a growing

social business, burns

rice husks to generate power

and provide electricity to

low-income Indian villagers. (Photo by Harikrishna Katragadda/Greenpeace)

Husk Power Systems, a growing

social business, burns

rice husks to generate power

and provide electricity to

low-income Indian villagers. (Photo by Harikrishna Katragadda/Greenpeace)

Bihar is far from the economic growth that has transformed Indian megacities like Mumbai, Delhi, and Chennai. It has the lowest rate of economic activity of any Indian state ($430 a year GDP per resident); between 80 and 90 percent of its villages have no electricity; and many of these villages are so remote that the government has declared them unreachable with the conventional electrical grid, consigning millions of people to darkness and poverty.

Gyanesh Pandey, Ratnesh Yadav, and Manoj Sinha knew there had to be a way to address this issue. In 2005, costs for producing renewable energy had been dropping globally, and they believed this represented an opportunity for Bihar to become part of India’s story of economic transformation. They experimented with different sources of renewable power and ultimately settled on rice husks. Bihar is in India’s rice belt, and the husk left over from milling rice grains is not only plentiful, it is generally considered a waste product as well. By developing their own small, low-cost, rice husk-fired power generators, the team believed they could produce reliable, renewable, and affordable electricity for the 70 million people who were off the grid.

The first plant the three social entrepreneurs built in 2007, using their own personal savings, looked modest. It produced just 30 to 35 kilowatts of power, required three operators to keep it running eight hours a day, and delivered power to about 400 homes in the surrounding village over low-voltage power lines strung up on bamboo poles. The economics of delivering power through this system were attractive, and the team believed that this new, small-scale design and mini-grid could be the key to lighting up rural India.

Although excited about the promise of the business, the team’s personal bank accounts were nearly depleted by the cost of developing and building this plant. With a business plan in hand, in 2007 they entered and won three business plan competitions at the University of Texas, the University of Virginia, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, netting them $97,500 in prize money. They used this money to construct and operate a second power plant, pay their growing team, and continue their research and development.

The three entrepreneurs also began talking to potential investors about investing in their company, named Husk Power Systems. Although there was some interest, the feedback they got was that the business was at an early stage and too risky for investment. The team was at an impasse. Between their personal savings and prize money they had invested nearly $170,000 into the company. They had two pilot sites up and running, providing about 800 customers in Bihar with access to clean and affordable power. But they still couldn’t raise the capital they needed to grow their business.

Husk’s story is not unique. Many other companies whose mission is providing the poor with critical products and services face similar challenges. Despite the growing numbers of impact investors and the billions of dollars pouring into social impact funds, entrepreneurs like Pandey, Yadav, and Sinha still have a tough time raising the money they need to grow their businesses. Philanthropy and prize money will only get them through the seed stage of development and is not enough to adequately fund an ongoing business, yet few investors will fund a company like Husk in the early stages.

Although many impact investors care about social impact, their primary goal is to generate a significant return on their investments. And despite its social promise and the huge demand for its service, a social business like Husk faces a daunting set of challenges: poor infrastructure, customers with limited ability to pay, the challenges of attracting talented managers, and nonexistent supply chains. These barriers mean additional costs and additional risks, and early-stage investors will very rarely realize high financial returns on their investments to compensate them for taking on these risks.

As a result, most investors, even those who care about impact, choose either to avoid these companies altogether or to invest at a later stage when the execution risk is lower or when the risks are better understood. This means that early-stage companies like Husk find it difficult to raise capital to grow their business. This hampers the growth of the market, and, ultimately, keeps poor people from accessing high-quality goods and services that can improve their lives.

In many ways, the Husk story reminds us of the early days of microfinance: a social entrepreneur (Muhammad Yunus) willing to look beyond conventional wisdom and experiment with marketbased approaches (loans, not charity) to serve the poor (Bangladeshi women). It’s easy to forget how revolutionary an idea microfinance was, and how much time and money it took to go from the seed of an idea to a global industry that today serves hundreds of millions of poor people with a critical service to improve their lives.

The question that entrepreneurs, impact investors, and everyone who believes that business can play a role in alleviating poverty must answer is this: What will it take to replicate the successes of microfinance in other critical areas such as drinking water, power, sanitation, agriculture, health care, housing, and education?

Rise of Impact Investing

Interest and activity in impact investing is booming. Since 2010, many of the major development agencies and development finance institutions have either launched their own calls for impact investing proposals or accelerated their direct investments into impact investment funds. In 2011 the Global Impact Investing Network and J.P. Morgan published a report predicting nearly $4 billion of impact investments in 2012, and as much as $1 trillion in the coming decade. At the 2012 Giving Pledge conference, whose billionaire attendees have pledged to donate at least half their wealth to charity, impact investing was the “hottest topic,” according to The Economist. And a 2012 Credit Suisse report affirmed J.P. Morgan’s claim that impact investing is a $1 trillion-plus market opportunity. Although these predictions are at a minimum ambitious, and at a maximum wildly inflated, there is no doubt that impact investing has captured the world’s imagination much as microfinance did before it.

The promise of impact investing is undeniable, but we believe there is a growing disconnect between the difficult realities of building inclusive businesses that serve the poor and the promises being made by many of the newer, more aggressive funds and financial institutions. Part of the reason for this disconnect is definitional. Clearly, when J.P. Morgan and Credit Suisse talk about a $1 trillion impact investment market they are using the broadest of definitions. Much of the capital that now qualifies as “impact investing” is invested in more traditional businesses in developing markets (such as real estate, large-scale infrastructure, shopping malls, and aluminum factories), a trend that has been going on for decades and that has accelerated because of the strong economic growth in many developing countries. In addition, there’s been a huge growth in clean tech investing (which some include in their definition of impact investing): According to a 2012 McKinsey & Co. report, up to $1.2 trillion could be invested in solar alone over the next decade. But only a small subset of these funds is investing in social businesses like Husk that target low-income customers in developing countries.

A broad definition of impact investing is in many ways appropriate because nearly all of this capital has the potential to create positive impacts on society. But a broad definition also masks the fact that most funds—even those that talk about fighting poverty—bypass the more difficult, longer-term, and less financially lucrative investments that directly benefit the poor, and instead gravitate toward the easier, quicker, and more financially lucrative opportunities that target broader segments of society.

Today, only a small subset of impact investing funds are willing to take on the high risks and low- to mid-single digit annual returns that come with investing in these markets. This is particularly surprising given the actual track record of the global venture capital industry. According to a recent study by the Kauffman Foundation analyzing the investment returns of its $250 million invested in 100 venture capital funds, only a third of these funds exceeded the returns available in the public markets and, as an overall conclusion, “the average venture capital fund fails to return investor capital after fees.” If Kauffman’s experience is representative, it suggests that venture capital investing has not adequately compensated limited partners for the high risk and low liquidity of these investments. Nevertheless the rhetoric in impact investing is that “market” rates of net return should be 10 to 15 percent per year or higher.

Realities on the Ground

To better understand the subsector of impact investors and other funders that focus primarily on supporting companies that directly address long-standing social inequities, especially global poverty, we undertook a research project funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Specifically, we wanted to understand the sources of capital available to early-stage entrepreneurs focused on low-income markets, why it is still so difficult for them to raise money, and what it takes to scale up new businesses in these markets.

Our starting point was the research that Monitor Inclusive Markets (a unit of Monitor Group) had already undertaken of more than 700 businesses in India and sub-Saharan Africa. We then conducted a broad overview of the impact investing market—mostly at the fund level to understand investment strategies—and then undertook an in-depth look at Acumen Fund’s $77 million investment portfolio in 71 companies in India, Pakistan, and East and West Africa.

We pored over reams of data, including detailed social, operational, and financial performance information from Acumen’s portfolio as well as detailed reports on capital sources, including grants and subsidies. With early data in hand, we tested our hypotheses and initial findings by conducting extended interviews with more than 60 sector experts—investors, entrepreneurs, policymakers, and donors. Because we had access to the full Acumen database, we conducted deep-dive investigations into more than 20 companies, the first time an impact investor has submitted its portfolio results for this kind of external analysis.

Building an Inclusive Business

One of the first things we learned is that creating and growing a company like Husk is difficult, much more difficult than building a traditional business. These social entrepreneurs are truly pioneers. Not only are they aiming to provide new products and services to customers with both low incomes and an appropriate aversion to changing long-standing practices, these entrepreneurs also need to overcome the additional challenges of poor physical infrastructure, underdeveloped value chains, and thin pools of skilled labor to build their businesses. As a result, costs rise, time horizons lengthen, and roadblocks come up—all of which can be overcome, but it takes time and money to do so.

For Husk, for example, building a mini power plant that could generate energy from burning rice husks was challenging enough. But to make the innovation commercially viable the company had to develop a consistent source of rice husk, string wires on bamboo poles to connect every house in the village, create an electronic metering and payment system for customers with no credit history, and create Husk Power University to recruit and train the mechanics, engineers, and operators needed to run the plants. Although a new power company in a developed market would just build a plant or rebrand and resell power, Husk had to build a fully vertically integrated company that does everything from sourcing feedstock to producing power to deliver to people’s homes to collecting payment. Each of these pieces of the value chain is critical to Husk’s commercial viability, but they layer on additional direct costs and add degrees of difficulty to the successful execution of the company’s business plan. From an investor’s perspective, that means higher costs and more execution risk without larger financial returns, because Husk’s customers, even if there might be millions of them, have a limited ability to pay for power.

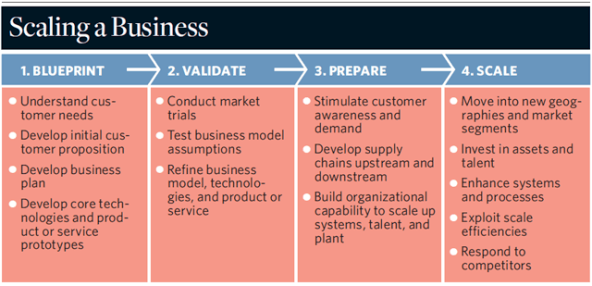

To better understand Husk’s evolution, consider the four stages of development that a new, pioneering enterprise undergoes: blueprint, validate, prepare, and scale. (See “Scaling a Business,” above.) Pioneering social entrepreneurs have an idea and develop plans—a rough blueprint—for a business that could disrupt the status quo and make a dent in a big problem. The entrepreneurs then take their ideas and begin market tests that require multiple rounds of trials to prototype, refine, and validate the business model, to learn that the product or service works and that customers are willing to buy it at a price that will provide a sufficient return to support the company in the long term. Next, the company needs to prepare for growth, both internally (for example, strengthening the executive team, board, governance, and operating systems) and externally (for example, stimulating customer demand for its products and establishing effective distribution channels to get its products to the customer). Only then is the company in a position to scale up the business.

The Pioneer Gap

One of the most striking findings of our research is that few impact investors are willing to invest in companies targeting the poor, and even fewer are willing to invest at the early stages of the creation of these businesses, a problem that we call the Pioneer Gap. Monitor found that only six of the 84 funds investing in Africa offer early-stage capital. This finding was confirmed by interviews we conducted with nearly 30 impact investors: The overwhelming majority of these funds and advisors expressed a strong preference for investing in the later stage of a company’s development—scale—after commercial viability had been established and preferably once market conditions were well prepared for growth.

The reason this happens is twofold. The first is ideological, the belief that by definition anything that uses investing tools must hit market rates of return—without a clear definition of which market those returns are based on. The second reason is structural: Most of the money going into impact investing still relies on traditional fund structures with traditional return expectations. Funders look to investors to realize significant financial returns and create social impact, but in practice the financial returns nearly always come first for funds with external sources of capital.

What our research uncovered is that although there certainly are many businesses with positive social impact and promising financial prospects, businesses that directly serve the poor nearly always operate in environments that make outsized financial returns extremely unlikely. At Husk, for example, the costs of building out each piece of the supply chain may never provide financial returns for investors, and yet without Husk or someone else taking on these costs, the business will never grow and millions of Biharis will continue to live without power.

Viewed through a purely financial lens, the decision not to invest in Husk at a very early stage makes sense. The early stages of a social business are beset with complexities—all the challenges of a traditional startup, multiplied by the very difficult operating environment—and a potential investor will be unlikely to realize outsized financial returns within an acceptable time frame (typically five to seven years). Viewed through an impact lens, however, this approach makes no sense. Impact investing was meant to fill the gap faced by companies like Husk. And although there is certainly much more capital available than there was just five years ago, most of it is for later-stage investing.

Understanding these limitations, early-stage social businesses tend to look to other sources of funding, particularly grants. Our analysis shows that most social businesses—whether in Acumen’s portfolio or in the broader landscape surveyed by Monitor—had received meaningful grant support early in their development. Of the 71 companies in Acumen Fund’s portfolio, 67 received grants at the blueprint, validate, or prepare stages. These grants paid for the market development costs that companies serving the poor must meet in order to function.

Husk provides an excellent example of the role strategic grants play in building an early-stage social business. Pandey, Yadav, and Sinha had established a blueprint for providing off-grid power in Bihar, but were having limited success raising early-stage capital to complete the validate stage of their growth. In 2008, with two power systems up and running, the Husk team met Simon Desjardins, program manager of the Shell Foundation’s Access to Energy program. Desjardins’s goal was to bring modern energy to low-income communities by backing promising ventures in emerging economies, and Husk seemed to fit the bill.

Fortunately for Husk, Desjardins was not a traditional program officer, and Shell was not a traditional grantmaker. Rather than simply make a grant to Husk to help it provide power to more villages, Desjardins asked an atypical question: How could grants help Husk get to a point where it would be more attractive to investors? Desjardins and the Husk team set out to determine what investors would need to see in order to fund Husk. They agreed that investors expected the team to have more plants in place, to lower the cost of each plant, and to demonstrate the ability to build plants and sign up customers more quickly and efficiently.

So Shell’s grants were tied to Husk hitting a series of operational milestones. The first grant called for Husk to build three additional plants in six months—faster than they had built them before—and maintain consistent uptime at each plant. Later grants pushed the company to reduce the cost of building a plant, develop a proprietary payment system, build local mini-grids, create and implement health, safety, and environmental safeguards, and establish Husk Power University. In total, Shell gave Husk Power $2.3 million in grants between 2008 and 2011 to hit these milestones.

In addition to the Shell grants, Husk benefited from a new policy by the Indian Ministry of New and Renewable Energy to give a capital subsidy to companies providing power to off-grid villages. This significantly reduced Husk’s out-of-pocket costs to build a plant and helped individual plants reach profitability within an acceptable time horizon.

Meanwhile, from 2007 to 2009 Husk stayed in active conversation with Acumen and other potential investors. By late 2008, with 10 plants in place and having hit nearly all of the milestones called for in the early Shell grants, Husk was finally ready to attract impact investors. The company was still small—with fewer than 10 plants serving a few thousand households—and years away from profitability, so the risks were still high. Yet Husk had enough of a track record to attract a $1.65 million pre-Series A round of investment led by Acumen Fund, with participation by LGT Venture Philanthropy, Bamboo Finance, and Draper Fisher Jurvetson.

Since 2009, Husk has grown from 10 to 75 plants and is on track to open hundreds more in the coming years. Strategic grants, a well-executed public subsidy program, and investor capital came together to help Husk’s team reach these impressive milestones.

Enterprise Philanthropy

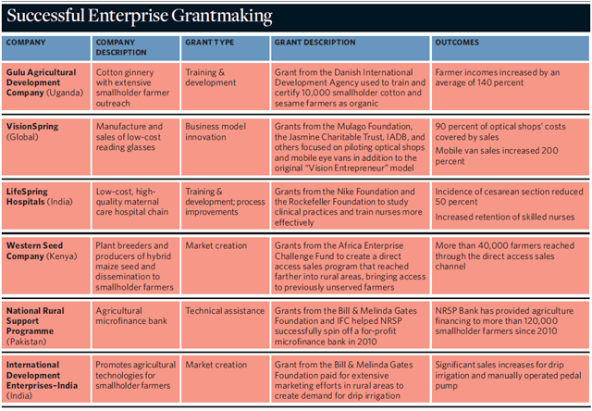

Husk’s early growth required a combination of founder money, targeted grants aimed at achieving specific operational milestones, public subsidy, and impact-focused investors willing to take an early bet on a promising young company. Across the Acumen portfolio we see the most successful companies walk a similar path, balancing the needs of multiple stakeholders and finding creative ways to attract different types of capital at different stages of their growth. (See “Successful Enterprise Grantmaking,” below.)

One of the most critical sources of funding at the early stages of a company’s growth was from what we call “enterprise philanthropy.” This kind of philanthropy—exemplified by the grants given by the Shell Foundation—provide grants along with ongoing, hands-on support to help companies move from the blueprint through the validate stage of their development. Enterprise philanthropists are not only willing to make grants, they are also willing to invest time and money in social businesses at the early stage of their growth. By doing so they are helping firms bridge the Pioneer Gap.

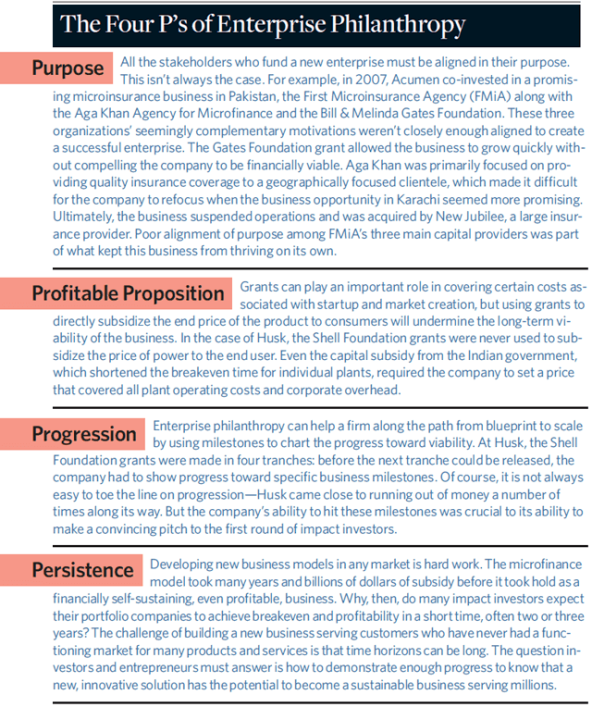

Not every grant to a company qualifies as enterprise philanthropy. A successful enterprise grant will accelerate the development of a social business and position the business to take on investor capital. Enterprise philanthropy, as distinct from traditional grantmaking, has four distinct characteristics: an aligned purpose; a focus on a profitable proposition; clear progression through operating milestones; and persistence through the many cycles of iteration of a new business model. (See “The Four P’s of Enterprise Philanthropy,” below.)

In our research we saw examples of successful enterprise grants as well as other grants to companies that clearly failed. When the grants failed, it often was because there wasn’t an alignment of purpose between grantmaker, investors, and the company, or the grant did not help the company get to a profitable proposition. Enterprise grantmaking is difficult in practice. It requires a high degree of engagement and successful management of previously strange bedfellows (donors, entrepreneurs, and investors).

It is therefore not surprising that giving grants to a business is not something that most philanthropists are used to doing. If anything, enterprise grantmaking runs counter to traditional philanthropic practice. In Shell’s case, grant money was used to build a local talent pool, develop metering systems, and create safety standards and practice—costly investments in the value chain that a traditional power company in the developed world would not have to make. Although Shell understood the potentially catalytic effect of these targeted grants, most grantmakers would not feel comfortable giving grants that don’t have a direct impact on villagers’ lives.

Bridging the Pioneer Gap

The reason the Pioneer Gap exists is the persistent misalignment between the demands of investor capital and the economic realities of building businesses that serve low-income customers. The risks of investing in these types of businesses are simply too high and the financial payoffs too low to consistently realize funds’ expected returns.

Philanthropy and other grant capital, including public funding, have an important role to play in closing this gap. As the Husk example illustrates, direct grants to the company and a government subsidy program both played significant roles in accelerating the growth of the business without distorting the end market for affordable power in rural Bihar.

The big question is whether enterprise philanthropy can grow large enough to meet the need. Enterprise grantmaking is hard to do, it often requires hands-on support and high engagement, and it is different enough from traditional grantmaking that it will feel very foreign to most grantmakers. It is hard to imagine a world in which billions or tens of billions of dollars of enterprise philanthropy flow into the sector as direct grants. The challenge is not just the availability of philanthropic capital and the mindset shift that would have to occur on the part of grantmakers, it is also that an entire infrastructure of enterprise grantmakers, on the ground and able to work directly with companies, would have to be built globally. This is certainly possible, but it is daunting.

A complementary solution to addressing the Pioneer Gap is to increase the supply of impact investment capital whose risk/return profile is aligned with the realities of early-stage companies in remote, underserved markets. Despite the rhetoric of the impact investing sector, our interviews affirm that most impact investors won’t invest in the early stage. And why would they? Most impact investment funds are backed by limited partners who expect returns of 10 to 15 percent per year or higher. Although there’s no doubt that some risky early-stage ventures with huge potential social impact will offer these levels of financial return, our research shows that most of these early-stage companies do not offer a sufficiently attractive investment proposition to hit this financial benchmark across a portfolio.

The clear solution is to create more investment funds that have more moderate financial return targets—for example, 5 percent per year or lower. These funds, whether investment capital or philanthropy, would be designed to look for the highest social return; those structured as investment funds would hit a minimum threshold of financial return. This orientation would be the exact opposite of what is predominantly happening in today’s impact investing market, where financial returns are paramount and firms must hit minimum social impact targets.

What might such funds look like? The simplest and most attractive approach is for limited partners to make their social impact thesis more rigorous and explicit and then offer capital to investment funds that will commit to hitting these social targets while offering a more modest rate of financial return. To make this work, the investment committees of the major institutional funders—many of them government bodies funded by public monies—would have to be comfortable having a subset of their investment capital explicitly structured to tolerate lower financial returns in order to achieve more aggressive social impact targets.

Another approach would be to build more blended investment funds that combine investment capital with philanthropic or technical support funding. For example, a new $50 million investment fund could also raise a $10 million philanthropic fund—this approach is similar to the recent fund raised by Grassroots Business Fund. The advantage of this structure is that it gives the investors freedom to deploy targeted grant capital to their investees, much like the Shell Foundation did for Husk Power Systems. In addition, by having the investor provide both the grant and investment capital, getting alignment of purpose toward creating a profitable business proposition is a more straightforward undertaking. The challenge of course is that most investors are not adept at raising philanthropy, and many philanthropic funders do not want to feel they are subsidizing investors’ returns. So, although conceptually attractive, this approach has some limitations in practice unless individual investors prove more willing to provide both investment and grant capital.

Finally, at the most aggressive end of the impact spectrum, more funds could be created that are backed by philanthropic capital. Acumen Fund is one such model, as is any fund created from private capital that doesn’t have an explicit return expectation to external investors. Such philanthropically backed funds have the most flexibility to take early-stage risk and to test the limits of where markets will work to solve some of the toughest social issues.

Although it is easy to describe each of the three solutions above, it is difficult to make more of this funding materialize in practice. Investment committees are slow to change their investment theses and their risk tolerance, and it is challenging for a limited partner thousands of miles away from an investment to be able to distinguish between the kinds of impact different funds will actually have on the ground—meaning higher-return funds can look like they represent limited trade-offs in terms of impact. Harder still is to increase the supply of philanthropy, both because philanthropy is always difficult to raise and, more challenging still, because the growing orthodoxy is that impact investing can and should be funded by traditional investor capital.

One way to attack this problem is to have more fund managers and more funders experimenting with fund structures that more directly and appropriately align fund partners with the fund’s impact objectives: rather than use traditional fund structures that provide incentives to maximize fund returns (through carry), create funds that explicitly aim to maximize social impact while requiring a lower minimum return on invested capital. For example, a fund could have a bonus structure whose sole payout mechanism is a function of hitting social impact targets, instead of specific financial targets.

More broadly, the sector needs a mindset shift. For the impact investing sector to reach its potential, it needs to return to first principles and articulate what kind of impact we aim to create for which populations. Our research has shown us that unless we create a structural shift in the supply of capital, the Pioneer Gap will persist; businesses that most aggressively target the most difficult-to-reach people and the toughest social problems will continue to struggle for funding; and “impact” will be loosely defined rather than a core purpose of nearly all impact investing funds.

The Future of Impact Investing

The growing interest in impact investing is a sign of an emerging consensus: the time has come to use the tools of business and investing to achieve social good. In the froth of excitement surrounding impact investing, however, we worry that a limited notion of the tools of impact investing may be hamstringing its goal: to build and scale organizations that help to solve big social problems.

A close look at impact investing reveals myriad investing goals, theories of change, and financial return expectations. It is early enough in the life of the sector that no one philosophy or approach can confidently claim to achieve the greatest impact per dollar invested. But for any of these approaches to flourish, we need much more clarity about our definitions of success. Impact investing was created as a reaction to the limitations of single bottom line investing, yet ironically many of the newest impact investing funds have traditional private equity fund structures that expect high financial returns and that compensate fund partners on these financial returns without any explicit aim or incentive for achieving social impact targets.

At Acumen, the investing in impact investing has always been a means, not an end in itself. For most other funds that cannot be the case because of investor demands for high financial returns. One of the risks we face is that more and more of the capital coming into impact investing has impact as a secondary goal. Our research indicates that it is difficult if not impossible to have impact as a primary goal while generating consistent capital growth for limited partners. Driven by the traditional fund structures and return expectations, many fund managers will have no choice but to screen out all investments that promise anything less than significant capital growth. With that as a first screen they will quickly discover that they cannot invest in many of the most innovative, early-stage, high-potential businesses.

The result will be that the Pioneer Gap will persist, and many of the most promising social businesses will have to improvise to raise money. Philanthropic grants can play an important role in funding early-stage companies, but we worry that they do not have sufficient funds to meet the needs of the sector. Targeted government subsidies and funding can also play a role, but they have to date also proven to be insufficient. Without a structural change in the capital market for social businesses that attracts more impact investors, many will fail to bridge this gap.

The problem is not one of will. Many new and existing impact investors are doing this work because they care profoundly about social impact. But there are two major barriers to creating a well-functioning impact investing marketplace. The first is ideology—the simple notion that any investment involving trade-offs or submarket rates of return inherently is bad investing and is unsustainable. The second is a lack of imagination on the part of funders to create products that match the real needs in the marketplace.

Over the course of our study we heard a lot of frustration. Impact investors are frustrated that there are not enough investment-ready companies, which makes it hard for them to meet their stated financial and social goals. Social entrepreneurs are frustrated because in the early stages of the company’s development, when they need money most, impact investors won’t invest. The market has incredible potential, but this potential will be realized only if investing capital can align itself with the realities on the ground. And until the enabling environment for pioneering social businesses changes radically until we have better infrastructure, deeper talent pools, and more proven business models—investors will not be financially compensated for the risks they take.

Impact investing has come far as a sector. Just a decade ago, the notion that philanthropy could be used for investment was unheard of. The idea that direct grants to a for-profit company could be a mainstream strategy to fight poverty would have seemed absurd. The idea that pursuing social impact could be incorporated in an investing strategy—whether in public or private markets—was seen as a fringe notion. So much has become mainstream, so much more is possible, but only if we realize that we are just at the beginning.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Robert Katz, Harvey Koh, Ashish Karamchandani & Sasha Dichter.