Six years ago, when I met Karen Ortiz, vice president of early-grade success initiatives at Helios Education Foundation, I quickly realized that she was one of the most courageous and passionate early childhood advocates of our time. She was championing the Arizona Early Childhood Alliance, a statewide collaborative effort with the goal of developing an integrated early childhood system to help children succeed and to transform educational and health outcomes.

Cross Sector Leadership: Approaches to Solve Problems at the Scale at Which They Exist

This special supplement, sponsored by the Presidio Institute, takes a close look at cross sector leaders: how they are different from other types of leaders, the role that they play in advancing social change, and why they are so important today.

-

The Need for Cross-Sector Collaboration

-

The Essential Skills of Cross Sector Leadership

-

Cocreating a Change-Making Culture

-

Creating a Cross Sector Leadership Network

-

Profile: Hollaback Cofounder Emily May

-

The Progressive Resurgence of Federalism

-

Profile: FUSE Fellow Siobhan Foley

-

Profile: Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf

Most of the collaborative’s members had previously worked together on early childhood issues, and understood and trusted each other. The collaborative had been functioning for two or three years and was making excellent progress, with thoughtful, strategic objectives and priorities.

Ortiz knew, however, that to make a dramatic change in the lives of Arizona children, and to pivot from strategy to action, the collaborative would require a new type of leadership: one owned by several community organizations and stakeholder groups representing nonprofits, foundations, government agencies, and local businesses that embraced the shared outcome of early childhood success. She knew that a shared culture was necessary to achieve their desired results.

Enter culture-building, or the practice of building trust, aligning a group to believe in the change, defining ways of working or sets of behaviors that will lead to the desired results, and creating the space to take risks, innovate, and give and receive feedback to productively evolve the culture.

Building Culture Is Critical

Ortiz was right. As the late management guru Peter Drucker once said, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Research backs up his assertion in business, as well as in large-scale change. In 2011, Community Wealth Partners (where I serve as president) set out to understand why some social change efforts achieve dramatic impact on a problem while others do not. A subsidiary of the national nonprofit Share Our Strength, Community Wealth Partners supports foundations and nonprofits nationwide in solving problems at the magnitude at which they exist by partnering with leaders and communities to design and implement bold strategies, strengthen their capacity to make change, and learn and evaluate their efforts along the way.

We drew insights from various transformational initiatives, including the anti-malaria movement, which contributed to a 66 percent reduction in malaria deaths across Africa between 2000 and 2015; and the anti-smoking movement, which led to a 50 percent decrease in the smoking rate among US youth between 1997 and 2011. Our research isolated the elements most common among initiatives that achieved transformational change. In every instance, culture—one that is deeply understood and lived by stakeholders and connects specific behaviors to specific results—emerged as a necessary element in achieving transformational results.1

Culture involves the articulation and consistent, long-term promotion of the values, norms, and daily behaviors that allow people, organizations, and communities to align their actions in a disciplined way that contributes to progress. Culture is the great accelerant or deterrent of progress because complex human beings make change. Yet, culture is present, whether or not we are explicit about recognizing and developing it. Culture, therefore, is as much a part of the large-scale change process as developing strategies, engaging stakeholders, securing capital, and other work. If collaboratives are to truly transform communities, funders must finance collaboratives’ culture-building efforts.

Many collaborative leaders have begun to embrace culture as a critical part of their efforts, but culture is complex and difficult work. It requires leaders of diverse groups to be vulnerable with each other, be open to change—within themselves and within their organizations—and be honest about how power dynamics can distract us from what matters, or deter the pace of change. Therefore, culture work can help us deal with interpersonal dynamics between leaders, and relations among organizations and within the community.

Cocreating Partnership Principles

Our research and experience suggest that, while no two cultures will be the same, the primary characteristics of change-making cultures are transparency, authenticity, collaboration and partnership, racial and gender equity and inclusion, continuous learning and improvement, openness to risk and change, and, ultimately, outcomes. Rather than working in isolation, these values, or subsets of them, work dynamically to reinforce each other and create a stronger whole.

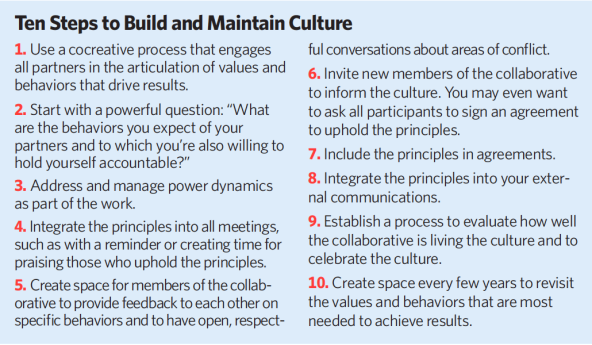

How can a collaborative develop such a culture? A first step is to facilitate a conversation about partnership principles—the core values that are the bedrock for collaboration, guiding how participants will interact with each other. They need to be clear, brief, and few in number (no more, say, than five), so that people can remember them easily. For example, they might include respectful dialogue, trusted partnerships, or equity and inclusion. While they should support all interactions, they will become particularly important in moments of conflict or heightened power dynamics; acknowledging them explicitly can help groups productively work through tense times.

After establishing principles, the next task is articulating the behaviors, or specific actions, that demonstrate how the principles are lived out and how they will lead to the group’s desired results. The most important outcome of these steps is a commitment by all collaborators to hold themselves and others in the group accountable to what has been established.

To facilitate commitment and accountability, the discussion can begin with this question: What are the behaviors we expect of our partners and to which we are also willing to hold ourselves accountable? For example, one of the principles that Ortiz’s collaborative created was “respectful dialogue.” One of the associated behaviors was to “seek first to understand and then to be understood.”

Answering this question reinforces a cocreative process, which is essential in building the deep commitment and longevity needed for individuals to take aligned action and sustain the work of solving social problems. This process helps collaborators recognize that in working together, they are building a culture that utilizes the talents and values of the different entities involved and is distinct from each participant’s own organizational culture.

The most effective collaborative cultures manage through the challenges when cultures collide and form a shared sense of identity and belonging that helps them to address common roadblocks, such as the speed of decision making and action, the level of transparency desired and allowed, and the willingness to take risks. Cocreating the collaborative’s culture also allows the group to harness and utilize the unique contribution of each participant and more easily identify distinct roles, which leads to more effective working relationships and greater progress. Nascent collaborative groups are often tempted to set up complex structures. Yet these efforts require much higher levels of trust. Starting small can be a more effective alternative. What’s more, it can help collaborative efforts build a critical baseline of trust.

For example, Newman’s Own Foundation supported food access and nutrition-focused grantees in establishing a collaborative, hypothesizing it would lead to better programmatic results. The grantees formed a learning network to foster trust and collaboration, and strengthen their leadership and outcomes. Preliminary findings demonstrate promising and unexpected outcomes: Collaborative members all reported benefits from participation, and two-thirds are formally collaborating with each other outside of the learning network.

Addressing Power Dynamics

To build a healthy change-making culture, collaboratives are adopting new practices and processes to recognize, equalize, and manage power dynamics. These power dynamics inevitably exist between funders and grantees, as funders hold the checkbook and the power that often comes with it. But power dynamics can also emerge around race, gender, sexual orientation, class, and other identities. However unintentional and unwanted power dynamics may be, they require our attention because they are a central part of what holds back progress. To make progress, we need to welcome those hard conversations, not just acknowledging the elephant in the room but inviting it into the work and offering it a seat at the table.

The Arizona Early Childhood Alliance looked to shift power dynamics by creating a flexible shared-leadership structure. It created roles for three co-leaders and set up a system whereby the individuals filling these roles could change on a rotating basis, which enabled different organizations to lead as the group shifted focus to different priorities and advocacy issues. Other funder collaboratives have adopted a one-vote policy allowing all funders, regardless of the size of their grant or their power, to have the same influence in decision making.

While some may avoid addressing power dynamics for fear of damaging relationships, those hard conversations actually build trust. Delving into conversations about power dynamics requires vulnerability and risk taking, ultimately helping build intimacy, grow trust, and strengthen relationships. While these methods do not eliminate funder-to-grantee or funder-to-funder power dynamics, and they certainly don’t remove systemic race and gender power dynamics, they do invite conversations that can create greater trust and more productive working relationships, precisely because they allow for an explicit acknowledgment of the power dynamics that are present.

Culture Is a Journey

Creating a change-making culture isn’t a onetime task. Collaboratives must continually nurture their culture, intentionally modeling the behaviors they value, giving new members of the collaborative the opportunity to shape the culture, and developing mechanisms to recognize situations when the culture is not being upheld, discuss them safely, and move to resolve tensions.

A collaborative’s culture will be tested as it responds to new dynamics, evolves its strategies, and engages new stakeholders. In our work with collaboratives, we’ve found it helpful to deliberately revisit the culture as often as every three years, to ensure that it is leading to the collaborative’s desired results. As Kelly Giordano, managing director of Newman’s Own Foundation, says, “Collaboration is a process, not a static state.”

As for Ortiz and the Arizona Early Childhood Alliance, the culture-building process has proved fruitful. As of this writing, the collaborative has 75 members representing 40 organizations. It recently hosted an early childhood advocacy day at the state Legislature, successfully preserving funding for the Move On When Reading program, which resulted in a $20 million funding increase as well as increases to childcare assistance and other human services programs. It has also designed recommendations for the Arizona Department of Economic Security to improve the reauthorized Child Care and Development Block Grant and developed an indicator and goal for Expect More, Arizona’s early childhood indicator tool that establishes statewide, mutually agreed-upon measures of educational progress.

The alliance has also confronted and eased challenges. Just this year, the group faced confusion about the roles and responsibilities of task force and subcommittee participants. However, the cultural norms established by the group helped them follow a clear decision-making process, resolve the confusion, defuse the tension, and move on productively. While the work can still be messy at times, the alliance’s culture and flexible leadership structure has helped the collaborative establish a unified platform that incorporates diverse voices and drives change in Arizona’s policies, programs, and services.

We all—foundations, nonprofits, governments, and corporations alike—have a role to play in creating the cultures that will facilitate the type of change we want to see in the world. If we do this well, we will have a better chance of building healthy communities and a just, equitable society.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Sara Brenner.