(Photo courtesy of Secure Fisheries)

(Photo courtesy of Secure Fisheries)

The 2008 banking crisis cost the country of Iceland a larger percentage of its economy than any country has lost in any previous financial crisis. In retrospect, this was predictable, as the likely long-term consequence of a financial system deeply entwined with risky financial instruments. So why wasn’t it predicted? When a special commission investigated why it hadn’t been foreseen and prevented, they concluded that while there was identifiable negligence on the part of individuals, “the most important lessons to draw from these events are about weak social structures, political culture, and public institutions.” The commission concluded that the crisis was not only preventable, but that a pattern of short-term decisions had led to this risk being ignored.

A decade later, Dr. Ashish Jha said of the predictable and preventable COVID-19 death toll in the United States that “We got the medical science right. We failed on the social science.” There is a pattern here: When a preventable disaster loomed on the horizon, behaviors didn’t change and institutions or people failed to act until the situation had already reached the point of crisis. Dr. Jha identified also identified the roots of this pattern in social science. Our decision-making processes are well-designed for a host of evolutionary and social needs—and in most contexts the results are decisions which meet our short-term goals—but they are not necessarily adapted to reducing long-term risk.

Social impact organizations, armed with the knowledge of what these biases look like, can work to create the social contexts in which the same underlying biases that cause short-term decisions can instead lead to long-term benefit. In this way, by understanding the basics of decision making and building interventions which align long-term behavior with the needs of people in the moment, social impact organizations can address long-term problems.

With many competing issues clamoring for attention, people make decisions quickly, and in most circumstances on the basis of fast, generally accurate heuristics or mental shortcuts. Moreover, even when making decisions in a careful and thoughtful manner, our decisions are skewed towards meeting deeply-held “social motives”: the need to feel good about ourselves, to feel connected to others, to have a stable understanding of ourselves and the world, to feel agency in our ability to interact with the world, and to see fairness and justice in the groups that we belong to. But while these cognitive processes (and social needs) helped us survive as social animals in a complex and dangerous world, they mean that—in the aggregate—people are not great long-term thinkers. We tend to display a preference for the status quo and for decisions that reassure us that the world is more stable and less threatening than it perhaps truly is.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

In such a context, it’s perhaps not surprising that we can point to so many cases of “irrational” behavior or failures to respond to predictable issues. Icelandic financiers were rewarded both economically and culturally—as individuals—for decisions that ultimately undermined collective stability, pitting these concrete and immediate benefits against a vague and uncertain risks. In the United States, pro-vaccination communications (from the CDC and others) reached people who were getting competing information from many different, trusted sources. When people were confused and unsure about who to listen to, many would choose to listen to those who gave reassuring messages about how risks were low and reinforced optimistic biases.

For this reason, social impact organizations must do a better job of creating environments that encourage risk reduction behavior, especially in ways that authentically meet our social needs. For this reason, the 2022 UNDRR “Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction” calls for the design of “systems to factor in how human minds make decisions about risk,” while the World Health Organization has launched a “Behavioral Science for Better Health” initiative, and in 2021 the United Nations Secretary-General highlighted behavioral science as a key area to be developed to improve the UN’s collective impact.

What does bias-informed social impact look like?

For social impact organizations, the prevention of long-term problems means building systems that make risk reduction behavior the easiest and most attractive choice among the array of options. This has two basic elements. First, there is system design rooted in cognitive processes, such as behavioral economics models (and the behavioral nudges approach), which attempt to shape the social and informational environment around people so that short-term, heuristic-based approaches will tend to encourage positive behaviors. In other words, they make sustainable approaches the easiest option, using opt-out systems (rather than opt-in) or highlighting long-term choices over short-term choices. Second, people respond much more positively to choices and plans that they feel meet their social needs (things which reinforce values and beliefs that are important to them and help them feel empowered and relatively positively about themselves). Human-centered design or “behavioral design,” therefore, brings in elements of social identity and motive to develop systems built on the individual needs of the people affected. Systems that use both approaches provide a comprehensive approach to bias-informed work.

One example of this kind of bias-informed approach in supporting better systems can be found in the promotion of safe and dignified burials during the Ebola outbreak in Liberia. Because the bodies of people infected with Ebola can spread the disease, particularly during the kind of close contact that happens while preparing bodies for burial, an important part of the long-term resolution of Ebola was the safe burial of people who died. However, initial interventions in Liberia took place at a time when people were afraid and uncertain, and involved recommendations for burial that contradicted strongly held beliefs about how to respectfully bury the dead. Local communities resisted the interventions, while conspiratorial rumors about the malicious intent of the burial teams ran wild. As the groups working on burials assessed what was happening, they worked with local leaders and mapped the key concerns of communities in the area, so as to redevelop their approach. In doing so they focused on burial practices that, while safe, were more closely aligned with the needs and values of the communities affected. With this, the short-term decisions that contributed to a larger problem were shifted to solve the bigger problem.

How to develop this approach

As the Liberian case shows, a good way of operationalizing bias-informed impact is to blend the behavioral design approach with a careful consideration of groups and stakeholders involved in an issue and their needs and values. To do that, consider the following questions in sequence:

- What are the behaviors undermining the long-term goal? What specific behavioral change is needed? In the Ebola case, this was clear: there was a need to change burial practices to safer approaches.

- What are the major communities implicated in the impact you’re interested in? Such communities can be ethnic or religious groups, or any other group with a specific defined social identity. Each community will have its own values and social context, and targeted engagement with each may be necessary. In the Ebola case, the program implementers knew their major communities, as a part of their basic understanding of who they needed to reach with their outreach.

- For each community, what communication exists around the issue? What information and opinions do people receive and share? Among what sources? It is here, in the Ebola case (and in COVID as well), that initial design errors may have been made. It’s natural for technical experts to assume that their information will win out in a competition with alternative sources of information—thinking that, after all, their information is more accurate—but to most people it’s just one input in a competing network of other opinions and voices. The implementers of the safe and dignified burials program found that their initial work was contrary to the information that locals were receiving from trusted peers and community leaders. In part, they resolved this by working with local trusted leaders and ensuring that the information being received by participants was consistent from experts and other sources.

- For each community, what are the key values or social identity issues involved? If you want to change their behavior, what are the potential values-based conflicts that might come up? Do the requested changes run contrary to any specific deeply held beliefs associated with the community or identity? This values-based conflict was one root cause of the initial resistance in the Ebola case, and that resistance was addressed in part by aligning the requested behavior with the values and social norms of the community engaged.

Conducting this mapping and assessment at the early stages can allow the design of behavioral interventions that fit the local needs. Armed with this mapping, behavioral shifts towards long-term, sustainable solutions can be developed by understanding and building targeted outreach and engagement strategies based around the specific social concerns and values of the people involved. Using principles from the behavioral science research on what moves people to action, a systemic intervention can be built that connects to the social motives and interests of each primary community involved. Public health and disaster mental health specialists have developed excellent tools for implementing this approach cross-culturally: disaster mental health specialists Paul Bolton and Alice Tang, for example, have developed a “brief ethnography” model for quickly mapping and assessing local understandings and needs in order to quickly select appropriate interventions.

A specific model comes, appropriately enough, from Iceland. The Iceland Prevention Model (for the prevention of youth use of tobacco and alcohol) is built around a bias-informed approach that works with key stakeholders and influencers in local communities. It approaches prevention by identifying local neighborhoods and mapping the specific dynamics of substance use in each, then provides targeted data and messaging in a layered fashion to individuals, families, and schools to help create a whole-of-community understanding about the need for preventing substance use. In practice, this takes the form of identifying root causes driving substance abuse—that it is generally widespread, a lack of other ways to spend time together, a sense that it creates social connections—and through laws, funding for social programs, and community engagement making it harder to meet needs through substance abuse and easier to meet them through other ways. This model has been quite effective in Iceland, with rates of substance use declining since its inception while rates of positive behaviors such as spending time with parents climbed.

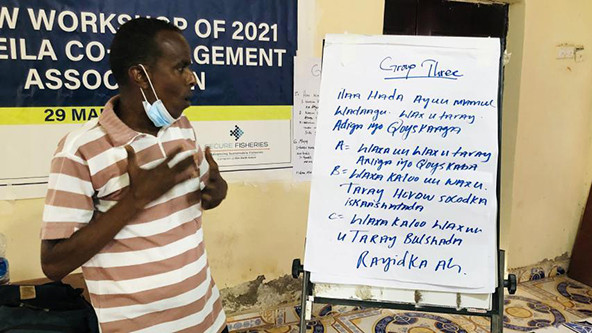

A second example comes from the work of Secure Fisheries, a program of One Earth Future (my organization). The management of natural resources, including fish, can be a source of violent conflict: issues of who controls these resources involve questions of economic benefit, but also questions of national and local pride as well as identity. As a result, systems that attempt to manage fisheries purely through national or regional governments disconnected from local concerns can drive conflict. Our work on these issues approaches the development of co-management structures for fisheries with the goal of also meeting the needs (including the social needs) of communities invested in fishing in the Somali region. By working with local governments and local communities, we work to help them identify gaps and needs in the governance system as a whole – areas where fisheries management is not providing the economic benefits it can, or where people feel insulted by or left out of local government’s management of these resources. We then support the creation of co-management systems that bring citizens into the official management of fisheries resources, and through the use of both skills training or education and capital investment by external funders help build local capacity for sustainable fishing as an economic engine. The result is not just an increase in economic activity, but a more systemic shift in relationships between local communities and governments: in 7 of 10 regions where our programs worked, conflicts around fisheries managements were seen as resolved by the people involved, and 75 percent of community participants in our program showed an increase in their trust in local government after our engagement.

The 21st century appears to be defined in part by the increasing risk posed by potentially catastrophic, but relatively long-term risks. From pandemics and climate change to economic instability and other risks, we are institutionally failing to prevent many problems which are identifiable over the horizon. Behavioral science can explain why this is, and models such as the Iceland Prevention Model and others demonstrate that it’s possible to develop good bias-informed approaches to complex problems and long-term issues. For those of us working in social impact, these examples provide some potential reasons for optimism, but also underscore the need to expand this kind of bias-informed work to address the multiple challenges facing humanity in the next century.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Conor Seyle.