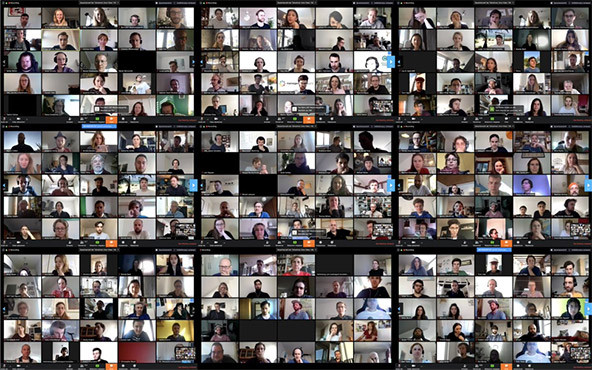

In March, 2020, a diverse group of more than 26,000 people participated in a hackathon designed to create solutions to the coronavirus. (Image courtesy of WeVsVirus)

In March, 2020, a diverse group of more than 26,000 people participated in a hackathon designed to create solutions to the coronavirus. (Image courtesy of WeVsVirus)

The inability of societal institutions to cope with a crisis warrants experimenting with a social innovation approach that rapidly brings together government, civil society, and the private sector. When civilian tech companies and organizations recently proposed an online hackathon to find solutions to the COVID-19 crisis, German politicians seized the opportunity and, within days, launched Germany’s first government-hosted crisis hackathon: #WeVsVirus, or #WirVsVirus in German. The effort not only produced viable and useful technical solutions, but also empowered thousands of participants to take action, learn, and create alongside others.

Hackathons are a novel organizing practice that have proven their worth in many different fields. They provide a dynamic, flexible setting, based largely on self-organization, in which creativity can flourish. Participants typically meet up in a physical space, form teams, and focus on solving a specific technical problem for a set amount of time. Hackathons are also a tool for driving open social innovation. In a governmental context, this means creating solutions to social challenges by opening up development to people and organizations outside government. Local governments like the City of Toronto, NASA, NSF, and the United Nations have all used hackathons to address social problems.

What made the #WeVsVirus hackathon unique was its unprecedented urgency and scale. Though guidelines usually recommend three months preparation time, #WeVsVirus came together in just four days, and organizers were overwhelmed by public interest in the event: A total of 42,968 people signed up and 26,581 participated, making it the world’s largest hackathon to date.

Set Up and Results

Organizers started by crowdsourcing problem domains and existing initiatives, and received 1,990 problem statements from civil society and government ministries. Screening of these statements lead to 809 problems, which they categorized into 42 challenges, including e-learning, neighborhood help, crisis communication, and digitalization of public services. Participants formed teams and chose specific challenges to address (more on this below). From there, they had 48 hours to develop and submit their solutions via the hackathon platform Devpost, and to create a two-minute video pitch uploaded to YouTube.

Over the 48 hours, teams generated a total of 1,494 project ideas. Together with industry experts and government officials, the hackathon organizers preselected the best 197 projects. Then the hackathon’s jury singled out the winning 20 projects, spotlighting them during an online ceremony held a week after the hackathon. Meanwhile, organizers and the German government launched a support program to help develop and integrate the ideas.

The first tangible result came on April 10, when Germany’s federal employment agency added one of the winning technologies—UDO, an online tool that helps employers apply for short-term labor grants—to its website. These grants enable employers to reduce employees’ working hours while receiving funding to compensate them for lost earnings. Though UDO is an add-on to an existing service, its development timeline was still impressively short: about two weeks from conception to implementation.

Beyond mobilizing civil society to come up with potential solutions to the crisis, the hackathon helped many participants overcome feelings of isolation and powerlessness by connecting them with 20,000 other like-minded, purpose-driven people. One participant shared that what stood out for her was “the euphoria, the positive energy and persistence with which people worked, developed ideas, and created innovations.” Sandy Jahn, a co-organizer who facilitated the feedback survey, pointed out other spillover benefits: “In addition to contributing to the greater good, participants enjoyed meeting new people and seeing participation as a learning process. What is more, 56 percent of the respondents say it strengthened the trust into the German government, 35 percent report no change, 8 percent say it weakened their trust.”

In the closing video call of the hackathon, German State Minister for Digitization at the Federal Chancellery Dorothee Bär said, “The number and depth of solutions is impressive. We should think about using the hackathon for other problems as well.” The success of #WeVsVirus makes it a valuable case study for governments and others interested in using hackathons to spark social innovation. Here are seven lessons decision makers can learn from.

1. Provide Community-Building Tools That Work

Hackathons can get messy, and online hackathons, just like physical ones, require a central communication and meeting space. Once you select a platform, it is crucial to understand its limitations and ensure that it works. Same goes for any other community-building tools. It’s also worth getting in touch with platform representatives beforehand so that, if you encounter problems, you can quickly reach someone who can help.

For #WeVsVirus, organizers established a channel structure for conversations using the chat-room application Slack. There was a channel for each challenge, which helped participants find teams. Other channels were dedicated to general announcements and dialogue with community managers, who responded to participants’ queries, maintained order in the Slack channels, and removed users violating guidelines. Meanwhile, private sector companies like Microsoft and Amazon Web Services provided server infrastructure.

Yet despite all this great organization and planning, the #WeVsVirus organizers soon discovered that Slack would not allow them to invite 40,000 users at once. The team worked long hours to resolve this issue, but while no-shows are always possible, this technical hiccup at the beginning might explain the gulf between 42,000 signups and the 26,000 people who actually participated.

2. Create Different Levels of Engagement

Participants bring various skills and levels of commitment to the table, so it’s useful for hackathon organizers to define official user roles in the sign-up process and to spell out the various ways people can participate.

#WeVsVirus organizers designed two possible user roles: project mentor and “regular” participant. The organizers recruited 2,922 mentors to help them cope with the sheer number of participants. Mentors supported the teams and helped spread vital information, and each had a unique digital identity in Slack so that other participants could easily identify them.

More active participants formed the core of their teams, while less active members completed minor tasks that aligned with their skills. Some participants did not join a team at all. Instead, they performed clearly structured tasks such as filling out surveys for a team that wanted to understand user needs, or answering questions from teams seeking opinions and expertise. Other users merely commented on live YouTube videos, or passively observed the process to learn more about it.

3. Support the Formation of Balanced Teams

Teams that know each other before a hackathon have a head start over new teams, but all teams need support—particularly when it comes to making sure they have access to the right skillsets for the problem at hand. Teams need more than technological knowledge; they need domain knowledge and expertise, and skills in areas like communication and user experience design. At the end of the day, balanced teams are more likely to produce viable prototypes.

The #WeVsVirus organizers helped create balanced teams in two ways. First, they created a Slack channel where participants could ask for help (such as an e-learning project requesting a teacher or education expert) and one where they could offer something (such as programming skills). Second, they tracked down mentors, and matched them with teams or individuals in need of mentorship in specific areas.

4. Establish a Range of Groups to Select Ideas

Opening up challenges to a crowd can generate lots of ideas. Organizers often underestimate the resources and effort it takes to distill feasible, impactful ideas—especially when there are thousands to screen. Deploying a multi-stage process and using a range of groups to assess ideas leads to better selection outcomes.

Events that use a jury should make sure the people on it not only reflect the diversity of the overall population, but also possess knowledge across the full range project types. Additionally, a public contest calls for some level of public vote, where the broader public can participate whether or not they signed up for the hackathon. Ideally, a public vote produces a shortlist from which a jury selects the popular winner. Relying entirely on a public vote could lead to unfavorable outcomes, as the story of a scientific vessel named BoatyMcBoatface reminds us.

For #WeVsVirus, an expert crowd composed of mentors and government officials first created a shortlist of top projects using a “10-eye” principle (each idea was evaluated by five experts). From that shortlist, a jury consisting of high-ranking governmental officials, academics, as well as leaders from businesses, nonprofits, and civil society, selected the best 20 projects.

This worked fairly well, but the process could have been improved in two ways. First, when the winners were announced, some criticized the absence of e-learning projects among them. One explanation for this is that no teachers or education experts were involved in awarding education projects. Second, the organizers abandoned the idea of a public vote in response to voices from the community arguing that public voting didn’t suit the spirit of a hackathon. While it was certainly worth considering the community’s concerns, canceling the public vote was a missed opportunity. Inviting the broader public to vote on all the submissions would have further increased awareness about the hackathon’s achievements.

5. Celebrate Collective Accomplishment and the Winners

Voluntary participation implies that everyone is intrinsically motivated. Still, it is important to acknowledge people’s hard work and celebrate collective achievements. Even when there’s no financial award for winning projects, the distinction helps gain attention and legitimacy, and thus attract resources. For everyone else, it just feels good to hear a public figure acknowledge your efforts and to know you contributed to something greater than yourself.

The organizers of #WeVsVirus highlighted participants’ achievements in various ways. In addition to the special online ceremony for the 20 winners, the #WeVsVirus organizers thanked each team during the final call and organized a virtual party with drinks and live techno music from a streaming platform supporting the Berlin club scene. In addition, State Minister Dorothee Bär personally congratulated the participants during the final call, and Acting Head of the Chancellery and Federal Minister for Special Affairs Helge Braun recorded a video praising the participants’ efforts. German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier even mentioned the hackathon in one of his speeches, saying the participants were among the “heroes in this time of crisis.”

6. Establish Programs for Scaling Up and Transferring Ideas

Of course, hackathons have their critics. Anjali Sastry, a senior lecturer at MIT Sloan School of Management, pointed out that hackathons can impede innovation by creating a false sense of success, producing flawed ideas, and failing to sustain the energy that it takes to cultivate innovative products after a hackathon. And in reflecting on her own hackathon experience, Harvard student Alison Flint emphasized the need for follow-up strategies to develop and scale ideas after the hackathon is finished.

It’s too soon to tell whether the #WeVsVirus organizers will overcome these issues, but it’s trying. Together with the government, corporate-backed foundations, and a range of companies, the organizers launched a post-hackathon support program to assist teams in realizing their ideas. The program consists of three elements:

- A matchmaking process for projects that need public or private institutional support to scale up their ideas

- Ongoing community management and collaboration support via Slack

- The promise of financial support—3,000 companies have expressed willingness to back projects financially, adding to financing generated from crowdfunding campaigns

Many projects moved ahead irrespective of this support, drawing on time the COVID-19 lockdown (involuntarily) freed up. Those who did apply lost time in the process, but it also helped solidify their commitment and gave them time to set up collaborations.

7. Embrace Transparency and Share Your Insights

While hackathons are messy and imperfect, transparency goes a long way toward managing expectations and instilling confidence that the organizers are doing their best and have nothing to hide. In addition, because using hackathons for social innovation is relatively new territory compared to corporate hackathons, it’s useful to openly share knowledge and best practices.

When Slack broke down at the beginning of the hackathon, co-organizer Adriana Groh apologized during the welcome call. The organizers were also open about cancelling the public vote. Despite some negative feedback, overall the community remained friendly and posted encouraging comments.

And in terms of sharing insights, Germany’s government-backed hackathon stirred interest throughout Europe, and the organizers shared their lessons in a recorded Youtube call with 90 people from other countries planning to organize hackathons. The European Commission recently held its own #EUvsVirus hackathon, and considering the first crisis hackathon started in Estonia at the beginning of March, it is impressive how quickly the world is adopting this social innovation practice.

When day-to-day life and the institutions we take for granted break down, social innovation needs to step in. Hackathons can kick-start innovation, but they can’t fix everything, and they’re no substitute for sound policymaking in times of crisis. With the UDO project, for example, the main social innovation isn’t the technology that came out of the hackathon, but the short-term labor grant policy itself. Technology can’t replace the urgent, collective decision-making we need to fix the social issues we face. That said, as long as organizers carefully orchestrate the process and foster collaboration between the different sectors and civil society, hackathons can make a difference. Coalescing around a common cause stirs hope in and empowers people, and can lead to new and viable solutions that ease the burden of social crises.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Thomas Gegenhuber.