Collaboration is appealing in concept but challenging in practice. While extensive resources—including ones from the Community Tool Box, The Intersector Project, and NewNetworkLeader.org—exist online to support collaborative efforts, the fact remains that we human beings are simply not very good at making “we” work. And yet, most changemakers today acknowledge that to address the complex social and environmental challenges we face we must learn how to collaborate—across organizations, sectors, networks, and differences. Effective collaboration must become a reality, not just an aspiration.

Most of us are familiar with the challenges of collaboration. Personality conflicts get in the way. Participants avoid difficult conversations. People are too formal and polite. We don’t take time to deliberately build trust. We don’t understand leadership in a collaborative context. And we fail to devote resources to essential coordination functions so that collaborations can truly flourish.

Building on the work of many others, we have developed a roadmap that cuts through the complexity. We have tested and refined this framework over years and across domains, and we tend to apply it in the spirit of statistician George Box, who famously said, “All models are wrong. Some models are useful.” We have found it to be useful and hope others will too.

The Five Cs: a roadmap for effective collaboration

While the why (the focus) and the what (the activities) of collaborations differ widely, the how (the process) is remarkably consistent. Launching and sustaining effective collaborations and networks requires that we pay constant attention to five activities:

- Clarifying purpose

- Convening the right people

- Cultivating trust

- Coordinating existing activities

- Collaborating for systems impact

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

These activities help us navigate the personal, political, cultural, and organizational dynamics inherent in collaborative efforts. They are never fully complete, and they are not strictly linear. They inevitably loop back and forth on each other, and require revisiting throughout any collaborative effort.

While it’s impossible to know exactly what’s going to happen until people actually get in a room together, the purpose of the roadmap is to outline the “deliberate” aspect of the collaborative process—the aspect that, to a meaningful degree, can be planned and facilitated. Here, we outline why each of these activities is important, what tactics can be applied to address each one, and how to put the framework into practice.

1. Clarifying purpose

Though a collaboration’s purpose—its reason for being—can evolve over time, an initial high-level purpose statement is essential to get people in the room. As leadership expert Simon Sinek said in his well-known TED talk, “Start with why.”

The purpose should be ambitious enough to inspire, clear enough to identify the right participants, and specific enough to focus the work of the collaboration. Collaborations can be bounded around an issue, geography, population, outcome, or combination of the above. For example, the RE-AMP network’s high-level purpose is to “reduce global warming pollution 80 percent by 2050 across eight Midwestern states.” The high-level purpose of the California Summer Matters Network is to “increase and improve the summer learning opportunities for all children and youth across the state.”

Clarifying purpose also entails making meaningful sense of the issue at hand. Albert Einstein famously said that if he had an hour to save the world, he would spend the first 55 minutes understanding the problem, and the last 5 minutes solving it. This process is what the design community calls “sensemaking.”

Sensemaking involves surfacing diverse perspectives, developing a shared understanding of the actors and organizations involved, and making sense of external trends and forces. It also involves understanding the local context, decoding the history of the place or system, identifying political and power dynamics, and unveiling hardwired assumptions.

Through this exploration of the system, participants begin to acknowledge their differences, while also recognizing the perspectives they share and the values they hold in common. This becomes a foundation on which participants can begin to act and eventually tackle the more-difficult conversations about issues they don’t agree on.

"The scarcest resource is not oil, metals, clean air, capital, labor, or technology,” systems theorist Donella Meadows once said. “It is our willingness to listen to each other and learn from each other and to seek the truth rather than seek to be right."

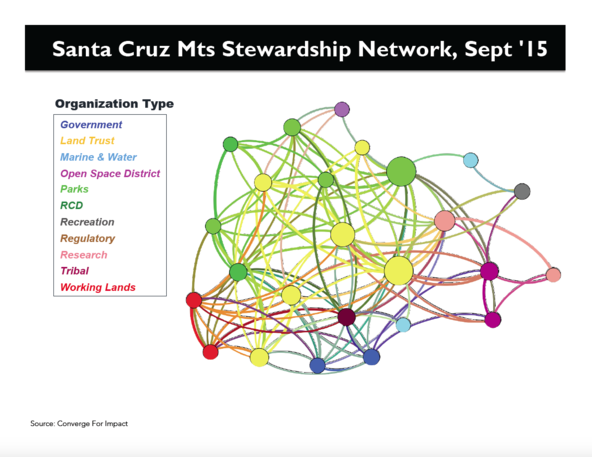

The Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network (SCMSN) is a region-wide, cross-sector collaboration of 19 organizations that are working together to improve land stewardship in the 500,000-acre region of California between San Francisco to the Monterey Bay. Participating organizations include federal agencies, state and county parks departments, land trusts, nonprofit organizations, the region’s largest timber company, research institutes, special districts, and the area’s largest Native American tribal band.

The network initially formed in late 2014 when a number of large public and private land owners and managers realized that although their organizations were all committed to caring for the region's natural resources, they weren’t working together on a scale that would be necessary for both the natural and human systems to thrive in the area. They knew they needed a collaborative approach, but they also knew that social fragmentation (the area had a history of tensions and mistrust) would limit progress.

Before the collaboration’s first meeting, we held in-person conversations with more 20 potential participants. Because these conversations were confidential, participants shared their honest thoughts, fears, concerns, and hopes for the collaboration. As expected, we heard concerns about hidden agendas and learned that participants had very different priorities in their day-to-day work. However, despite significant differences of opinion, there was also a meaningful amount of common ground. Participants generally agreed that effective stewardship required a “mosaic approach” that would accommodate a variety of land uses. They recognized the value of sustainable timber harvesting, and were aware of threats from real estate development and climate change. Importantly, everyone agreed that the region, as well as the work of each organization, would benefit from stronger connections and more collaborative relationships.

At the first convening, we anonymously reflected back what we learned to the whole group, acknowledging differences while highlighting areas of agreement. As a result, participants were able to begin crafting a high-level purpose statement just a few hours into their first gathering, thereby clarifying the collaboration’s reason for existing and charting a collaborative path forward.

Over the course of their first two convenings, participants also completed a historical analysis of the region, examined external trends and forces, considered future scenarios, and identified shared values. This sensemaking process helped the network evolve its high-level purpose statement into a memorandum of understanding, which all 19 members ratified at the end of their third convening. (For more details on the first two years of the network’s formation, see the case study here.)

2. Convening the right people

Convening the “right” people means bringing together whoever is needed to tackle the challenge at hand. Although there is no single correct answer to who to include, we agree with Marvin Weisbord and Sandra Janoff, creators of the “Future Search” planning process, who write: “The more far-reaching your objective, the greater your need for a broad selection of diverse players.” According to Weisbord and Janoff, this includes people with:

- Authority to act, such as decision-making responsibility in an organization or community

- Resources, such as contacts, time, or money

- Expertise in the issues under consideration

- Information about the topic that no others have

- A stake in the outcome and an ability to speak to the consequences

We would add two more. First, the “right people” include those who can listen deeply and consider diverse perspectives. As author Margaret Wheatley wrote, “Real listening always brings people closer together.”

Second, the “right people” are simply those who stay engaged. Over the course of any collaborative effort, it is normal—even expected—that some people will leave the initiative, and others will join as the collaboration evolves. In effective collaborations, the right people show up, stick around, and follow through.

Getting the right people in the room doesn’t necessarily mean issuing an open call to everyone who may have a stake in the effort. Open invitations are often motivated as much by the fear of appearing exclusive as they are by convening a broad selection of participants who need to be involved. Researchers at the University of Colorado Denver’s Center on Network Science have found that collaborations that begin and grow through “thoughtful inclusion” tend to exhibit greater long-term sustainability and effectiveness. Rather than engaging with all possible participants, thoughtful inclusion begins by recruiting a core group of committed individuals and organizations, even one by one, to clarify an initial purpose and plan of approach. As the initial group develops deep trust and cohesion, it invites additional participants to add necessary capacities and resources, and to increase the collaboration’s reach.

3. Cultivating trust

In our view, trust is the single most important ingredient of effective collaboration. Enduring relationships are not a “nice to have”; they are a “need to have.” The web of relationships that develops between participants is the invisible structure that makes collaborations work. Trust, however, has become something of a buzzword. Everyone says it’s important, but failing to cultivate trusting relationships is where most collaborative efforts fall short.

Google recently spent millions of dollars and thousands of hours to figure out why some teams stumble while others soar—an initiative called Project Aristotle. It reviewed a half-century of academic studies and studied hundreds of teams, struggling to find evidence for the common assumption that the composition of a team makes a difference. ‘‘We looked at 180 teams from all over the company,’’ said Abeer Dubey, a project leader, in a New York Times Magazine article about the initiative. ‘‘We had lots of data, but there was nothing showing that a mix of specific personality types or skills or backgrounds made any difference. The ‘who’ part of the equation didn’t seem to matter.’’

Google ultimately found that high-performing teams have high levels of “psychological safety,” as measured by an equality of turn-taking in team discussions, as well as high degrees of social sensitivity, or group members’ ability to read each other’s social signals. Psychological safety, as defined by Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson, is a ‘‘shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking,’’ and ‘‘a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone for speaking up ... It describes a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves.’’

In other words, people work together most effectively when relationships are strong and authentic. When they listen deeply to others and feel free to speak their minds. When they value diversity of thought and experience, and can tap into the unique gifts that each person brings. When there is a high degree of mutual respect and, in a word, trust.

Trust is not the same thing as “liking” or “agreement.” To work together, people don’t need to like each other. And they shouldn’t agree with each other on every issue. When we talk about trust, we mean trust for action—what we call “trust for impact.” The type of trusting relationships that can hold the tension through difficult conversations, engage in generative conflict, find a slice of common ground, and make collaboration a reality, not just an aspiration. We’ve also found it’s possible to build trust more quickly than most people think, as long as you go about it deliberately.

For the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network, we conducted a social network analysis just before the network’s first convening in March 2015, and every six months thereafter, to track and support the growth of these relationships. This data helped us to strategically “weave” connections across the network to maximize its potential for collaboration.

The network maps below illustrate this work. Each circle, or “node,” is a leader in the network. The colors indicate the organization type they represent, and each of the lines connecting the nodes signifies a personal or professional relationship between them. The network was initially fragmented, as seen in the first map, particularly in terms of the connections between different types of organizations.

In the second map, you can see that after only two convenings—during which we deliberately took time to establish a foundational level of trust between previously disconnected participants—the system became much more interconnected. Even if the network had never met again after September 2015, the region was now much more resilient than it was before the network formed. There were new and deeper relationships, stronger flows of information, and greater recognition of the opportunities for collaboration between organizations.

4. Coordinating existing activities

When people have identified a shared purpose and built trust, they are far more likely to seek out and follow through on opportunities to support each other’s work. This requires that participants share the work they are already doing that relates to the collaboration’s purpose. In the process, participants find opportunities to partner together, find quick wins, and avoid duplication of efforts.

Working together, even in small ways, allows participants to strengthen their relationships with one another, creating a virtuous cycle of trust and action. Analysis of the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, a collaboration of 60 communities throughout the United States working to create more resilience to wildfires, shows a strong statistical correlation between the depth of relationship between two participants and their perception of collaborative opportunities between them. In other words, as relationships develop, participants notice more opportunities to collaborate, which in turn strengthens their relationships.

However, the altruistic commitment of participants isn’t enough to sustain collaboration. On the contrary, collaboration must also serve the personal and organizational objectives of individual participants. Otherwise, they won’t be able to justify the time it requires to participate fully. This overlap between individual priorities and the collaboration’s shared priorities is what we refer to as the intersection of self-interest and shared interest, and finding a proper balance between the two is essential.

To this end, participants should have an opportunity early on in a collaboration’s formation to publicly identify their gives and gets—what they can give to the collaboration to support other participants and what they need to get out of the collaboration to make their participation worthwhile. The more specific the gives and gets, the better participants will understand one another’s conditions of engagement. Examples of gives include connections to funding sources or influencers, access to a volunteer base or a fleet of trucks, or time and energy to contribute to the work of other partners. Examples of gets include a professional grant writer, capacity or expertise to support a project, a conference room to host a meeting, or tangible outcomes from the effort.

Participants should also express legitimate constraints on their ability to contribute. Left unstated, others may perceive these limitations as a lack of commitment or a failure to follow through. Constraints may include issues such as the time participants can commit to the collaboration, the expectations of their board or senior leadership, and legal restrictions on their ability to participate in advocacy and policy change.

5. Collaborating for systems impact

For true systems change to occur, collaborative efforts must seek to address the root causes of problems, rather than just mitigating the symptoms. Actions to reduce immediate suffering, such as filling a cavity, are essential. But we will never produce lasting change without also addressing the root causes of the issue at hand, such as providing young children with quality oral care from the outset.

Getting at root causes necessarily requires acknowledging and addressing systemic and structural issues, such as racism, sexism, and income inequality. As Junious Williams and Sarah Marxer write in their article “Bringing an Equity Lens to Collective Impact”: “Without rigorous attention to persistent inequities, our initiatives risk ineffectiveness, irrelevance, and improvements that cannot be sustained.” And according to the authors of “Collaborating for Equity and Justice,” this requires that collaborations “embrace the principles of equity and justice and reexamine their membership, distribution of power and resources, social change agendas, and current commitments to an equity and justice work plan.”

One way to address root causes is by identifying and taking action on a set of “leverage points” that address the collaboration’s central purpose. Leverage points are places in a system where “a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything,” as Meadows has said. In a collaboration, leverage points also represent opportunities where participants can have greater impact by working together than they can by working alone.

100Kin10, a collaboration of more than 200 partners working to support STEM educators and train 100,000 excellent new STEM teachers by 2021, engaged hundreds of teachers to identify 100-plus challenges standing in the way of quality STEM learning for all students and to assess the relationships between these challenges. Through this process, 100Kin10 identified six primary leverage points to achieve its goal: 1) Raise state standards, 2) improve the quality of the curriculum, 3) expand financial support for STEM college majors, 4) develop accountability systems that promote teacher creativity, 5) increase the time available for professional development, and 6) increase the time available for teacher collaboration.

In addition to the comprehensive systems-mapping approach that 100Kin10 took, collaborations can identify leverage points through an in-the-room systems mapping exercise or through a design thinking approach that can help them move quickly from ideation to prototyping. Collaborations must then provide participants with structures to act, such as project teams focused on specific objectives. Participants typically engage when they feel they can have an effect, and where their organizational priorities align with the work of the team.

Putting it all together

In addition to the Five C’s roadmap, effective collaborations also require a degree of governance, structure, coordination, and funding to accomplish their goals.

Governance: As collaborations and networks move towards shared action, formal governance procedures can help participants make timely decisions, invite new members, design and facilitate convenings, and integrate a suite of online collaborative tools. The purpose of good governance “is not to tell members what to do, but to enable them to do what they want to do,” write Madeleine Taylor, Peter Plastrik, and John Cleveland in their article “Connecting to Change the World.”

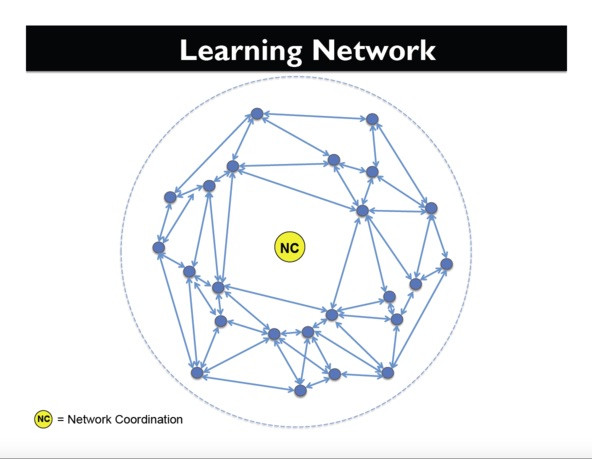

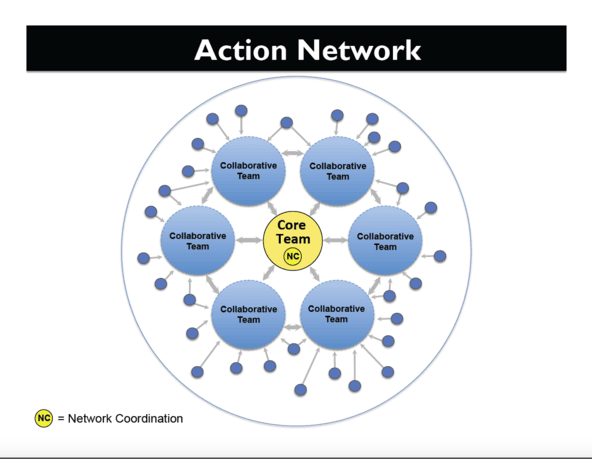

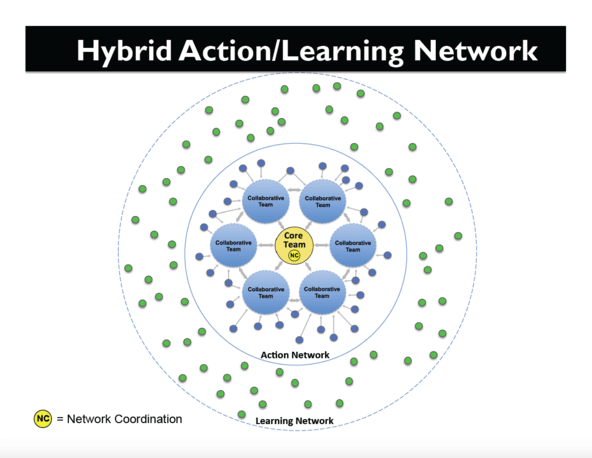

Structures: From our perspective, a network is the structure that operationalizes collaboration. The right network structure enables a collaboration to effectively channel the creative impulses of its participants. But too much structure risks stifling individual initiative, and engaging with too many rules and procedures. According to Frances Butterfoss, author of Coalitions and Partnerships in Community Health, “One should adopt the simplest structure that will accomplish the collaboration’s goals.”

Some examples of basic network structures that can support collaborations include:

- Learning networks, including the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network

- Action networks, including the RE-AMP Network

- Action/learning networks, including the California Summer Matters Network

- Network of networks, including the Network for Landscape Conservation

Coordination: Collaborations can’t achieve ambitious goals through self-organization alone. Some form of coordination is needed to mobilize a constellation of people and resources to address complex challenges. Those who perform these roles have been called systems leaders, systems entrepreneurs, network leaders, network entrepreneurs, strategic conveners, and accompagnateurs. Whatever they are called, their primary role is to coordinate.

The role of a coordinator, or team of coordinators, is to constantly sense and respond to the emerging needs of the collaboration as it evolves. They work to help participants clarify the purpose and the values they hold in common, identify who else needs to be involved, cultivate trust, find opportunities for mutual benefit, and catalyze collaborative action toward shared goals. Coordinators do not seek the spotlight. Instead, they are typically motivated by the collaboration’s purpose and their ability to help others achieve their potential for impact.

We have found it useful to think of coordination as a set of responsibilities that can be organized in three major areas:

- Front of the house: external communications, public relations and outreach, and resourcing

- Middle of the house: weaving, process design, meeting facilitation, conflict management, and member on-boarding

- Back of the house: logistical preparation for convenings, project tracking, evaluation, financial planning, and tech support

Funding: Collaboration is under-resourced. As the authors of the recent Harvard Business Review article “Audacious Philanthropy” write: “Collaboration of any type can be difficult and costly, so few philanthropists meaningfully support or engage in it, even though most are frustrated with the inefficient proliferation of siloed change efforts.” Yet foundations and philanthropists have a critical, unique role to play in supporting collaborations and networks.

The primary challenge for funders is to support collaboration without restricting or controlling its path. Funders must be willing to let the participants define a collaboration’s purpose and direction, or they run the risk of stifling the very energy that gives collaboration its potential for impact.

The S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation has found that it can effectively support collaborations and networks to pursue emergent solutions by:

- Allowing for flexibility in the collaboration’s objectives and deliverables

- Viewing the development of trust as a valid collaborative outcome

- “Making room” for other funders to support collaborative projects by investing in a network’s operational capacity

- Supporting specific collaborative functions, such as convenings, facilitation, and coordination

- Approaching collaborations and networks as a learning opportunity

- Being prepared to adapt their support as collaborations evolve over time

A decisive moment

Social philosopher Tom Atlee has written something that struck us as a good summary of what’s happening on the planet right now: “Things are getting better and better, and worse and worse, faster and faster, simultaneously.” If he is right—and we think he is—then we urgently need to consider two questions: How can we amplify the things that are getting better and better? And how can we minimize the damage from things that are getting worse and worse?

We believe the answer to both questions lies in cultivating effective collaboration—that is, meaningful attempts to work together on behalf of a shared purpose—across and between silos, organizations, sectors, and networks. From our perspective, it’s not an overstatement to say that our ability to work together effectively across all kinds of differences is the last great hope for humankind.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by David Ehrlichman, David Sawyer & Matthew Spence.