(Illustration by iStock/kanyakits)

(Illustration by iStock/kanyakits)

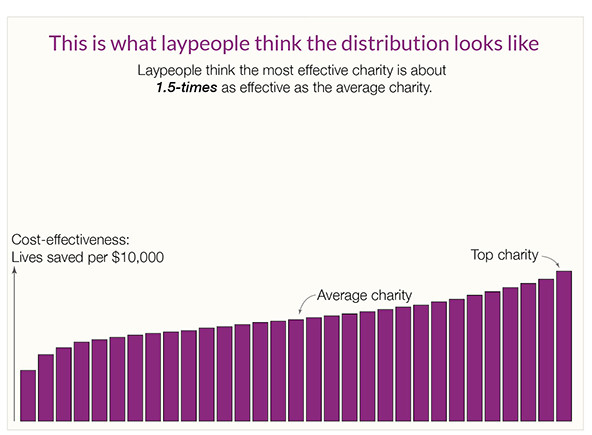

A couple of years ago, some clever researchers decided to investigate what they called “the puzzle of ineffective giving.” First, they asked a bunch of potential donors how much they thought the difference might be between the average charity and the most effective charity. Then they asked a bunch of experts. Max Roser—of Our World in Data—summarized their findings this way:

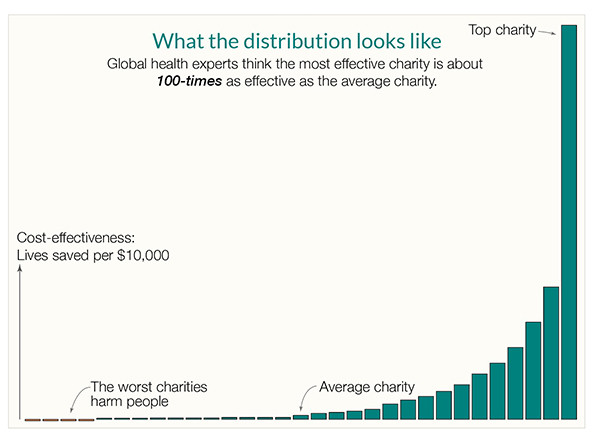

Illustrations based on the findings by Caviola et al (2020)—Donors vastly underestimate differences in charities’ effectiveness.

Illustrations based on the findings by Caviola et al (2020)—Donors vastly underestimate differences in charities’ effectiveness.

There are two big things to notice here. The first is that while most potential donors don’t think there’s that much difference in effectiveness between charities, the experts polled think there’s a huge difference. But the second is the stunner: According to these experts, below-average charities don’t accomplish much at all, and those to the very left of the graph actually harm people.

A friend who works with many NGOs rails about these useless charities constantly. He calls them zombies. He’s got a point: Zombies wander around the landscape, accomplishing little, but remaining animate as long as they can feed on human flesh. Replace “feed on human flesh” with “get funders to fund them” and the label is pretty much on point.

I used to blame those organizations, wondering why they didn’t work harder, smarter. The absence of accountability for impact is the bane of the social sector, and it seemed obvious that they were the prime offenders. But they’re not. It’s us, the funders. Money is the lifeblood of social sector organizations, we are the ones who allocate it, and we are the least accountable in the whole system. If there are zombies roaming the landscape, it’s on us.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Think about it. We—social sector funders—are the analog of investors in the commercial world. In that world, companies go broke if they don’t provide value for customers, and investors suffer when companies go broke. When an investment firm makes too many bad bets, it goes out of business. They’re accountable, and their bad decisions have consequences (mostly).

That kind of structural accountability doesn’t exist in the nonprofit world. Our customers—whom we often refer to as “beneficiaries”—have no way to express value or lack thereof. They have no say as to whether zombies live or die. If funders aren’t accountable for value—for impact—then nobody is.

And we’re not, not really. Accountability implies consequences, but people like me never get fired for lack of impact. You can lose your job because you said the wrong thing, because you slept with the wrong person, or because people don’t like you. But you will never lose your job because you failed to create enough change in the world. We can’t steal the money, we have to follow the tax rules, and we’re supposed to avoid double-dealing, but, fundamentally, we’re not accountable for results. We can fund all the ineffective stuff we want, and nothing will happen to us.

As a result, we’ve failed to create a functional market for impact, which means that money doesn’t flow efficiently toward those most able to create change. Zombies don’t die. They devour precious resources that should go to the living. We accomplish only a fraction of what we could.

Of course, nobody thinks they’re feeding—er, funding—zombies, but if we weren’t, they wouldn’t be there. Luckily, there’s a pretty simple way to keep your portfolio zombie-free: Don’t fund anyone who doesn’t do a credible job of determining their own impact. An organization that doesn’t determine its own impact is flying blind and you will be too.

What does it mean to do a credible job? Well, first we have to get to a shared definition of impact. Here’s a simple one: Impact is a material change in the world that makes it a better place. It’s an observable, quantifiable difference, which can be measured in terms of specific outcomes. We’re talking things like: kid’s lives saved, farmer incomes increased, deforestation prevented, more literate students, less CO2 in the atmosphere, HIV transmission prevented, cleaner urban air, rehabilitated fisheries, and rights achieved.

Impact is observable, knowable change, but more specifically impact is change that would not have happened otherwise—a phrase that itself captures precisely what philanthropy is supposed to accomplish.

Impact can also be defined by what it is not. First and foremost, activities are not impact. Trainings, workshops, delivering programs—that’s not impact. Nor are bogus metrics like “lives touched” and “people reached.” Awareness and attitudes don’t matter if it doesn’t lead to action; action doesn’t matter if it doesn’t lead to change. What people know, what they say, and what they do may be necessary steps on the way to impact, but it’s the end result that matters.

So if that’s impact, what does it mean to do a credible job of measuring it? Here are five steps to get there. To make them concrete, pick an organization at random from your portfolio. Ask yourself this:

- Mission: Do I have a clear understanding of what the organization is trying to accomplish—the specific impact they’re trying to create? (You might try the eight-word mission statement approach )

- Metrics: Are they measuring the right thing(s) to capture that impact?

- Change: Can they demonstrate that a change happened in terms of those metrics?

- Attribution: If a change occurred, can they make a persuasive case for what part of it was actually the result of their work? (An organization’s impact is the difference between what happened with them versus what would have happened without them—the “counterfactual”).

- Cost: If I know the impact, can they—credibly—tell me what it cost?

That’s a lot. It’s also non-negotiable if you really want to understand an organization’s impact in the world. I’ll be the first to admit that getting this right across a broad portfolio is forever a work in progress, but it’s your job and your obligation as a funder to keep banging away at it. You’d never be taken seriously as an investor if you didn’t understand profit, and you shouldn’t be taken seriously as a funder if you don’t understand impact. If you don’t want to get good at it, then hire somebody who is. Accountability for impact means that you commit to funding impact, you learn how to know if it’s happened or not, and you close the loop to make sure that it did. (Here’s Mulago’s attempt to articulate our own accountability.) Being accountable means that you don’t fund until you know what success looks like, and how it will be measured. It means that you learn from your mistakes and that you stop funding stuff that doesn’t work. It isn’t easy, but here’s the thing: The minute you start trying, you become part of the solution.

And being part of the solution does not mean that you avoid risk. Nor does it mean that you don’t fund important efforts that will take a while to get results. You can back start-ups and moonshots as long as you know what you’re getting into and when to get out. You can fund systems change as long as you know how to tell whether it is happening or not.

But whether you’re funding slam-dunks or moonshots, the onus is on you to figure out if it works and act accordingly. Impact is a moral obligation. We lack the built-in accountability of the commercial world, so we have to take responsibility for it ourselves. Boards need to hold executives accountable for it, managers need to manage toward it, program officers need to be obsessed with it, and wealthy individuals need to take their giving as seriously as they do their investments.

And the only way to make all that stuff the norm is to weave accountability into the culture of giving. People give for a lot of different reasons—to gain status, to assuage conscience, to feel agency, to relieve anxiety, to enjoy the pleasure of generosity—and we need to connect them all to impact, to make them unattainable without it. Figuring out how to do that is philanthropy’s biggest challenge, and making it happen should be our most urgent priority.

It should be our most urgent priority because here’s what could be different if funders were broadly accountable for impact: We’d harness market dynamics, and money would start to flow efficiently toward those best able to create change. High-impact organizations would find themselves holding a catcher’s mitt instead of a tin cup. Zombies would up their game and come alive—or die quietly. People would get paid commensurate with their contribution to impact (I’ve never understood why saving the world means you have to be poor) and more talent would come into the sector. More impact would create more faith in philanthropy and bring in more funders, and hence more—and better—doers. We’d see a quantum leap toward a better world.

I’m dreaming of a day when zombies go hungry and people like me get fired if we fail to create lasting impact. They say the best day to plant a tree is 20 years ago, and the second-best day is today. The world would be a different place if we’d all been accountable for impact these last 20 years, but here we are. It’s planting time.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kevin Starr.