(Illustration by Maggie Chiang)

(Illustration by Maggie Chiang)

In 2014, the keynote speaker at the Maternal and Child Health Epidemiology Conference told the attendees that we needed to stop talking about infant mortality. Since infant mortality was pretty much all anyone was talking about, the audience was stunned into silence.

Bringing Equity to Implementation

Implementation science—the study of the uptake, scale, and sustainability of social programs—has failed to advance strategies to address equity. This collection of articles reviews case studies and articulates lessons for incorporating the knowledge and leadership of marginalized communities into the policies and practices intended to serve them. Sponsored by the Anne E. Casey Foundation

-

Equity Is Fundamental to Implementation Science

-

Trust the People

-

Youth Leadership in Action

-

Community Takes the Wheel

-

Equity in Implementation Science Is Long Overdue

-

Listening to Black Parents

-

Faith-Based Organizations as Leaders of Implementation

-

Community-Defined Evidence as a Framework for Equitable Implementation

-

Community-Driven Health Solutions on Chicago’s South Side

-

Equitable Implementation at Work

Instead, the speaker invited us to think about racism as the true cause of infant mortality. His argument: No matter what your evidence base or scaling strategy is, there’s no hope of closing the infant-mortality gap, in which Black babies die at three to four times the rate of white babies, without acknowledging and addressing systemic racism and the oppression of Black Americans as the root of this disparity.

This point raises many questions about what to do with the programs we are already implementing: Should we stop implementing all of them? Or maybe select different programs? Or change the way we implement them? Or change the way we define success? How could we do any of this without a blueprint to consult?

Access to human services and their effectiveness vary a great deal depending on the population in question. Ease of access, service quality, and care outcomes all hinge on the population being served. In underserved communities, including those that have experienced barriers to access on the basis of race and ethnicity, immigration status, socioeconomics, sexual orientation, gender identity, and ability, access to interventions is often limited. Too often these groups receive services that have been developed and evaluated in contexts that do not represent them.

We imagine that many readers of Stanford Social Innovation Review are involved with programs, practices, or policies that aim to meet unmet social needs by using interventions designed to enhance well-being across a wide range of issue areas. We also imagine these readers have seen varying degrees of success in achieving desired outcomes, often for reasons that are unclear. Sometimes we achieve desired results and accept good outcomes without thinking too much about why or how we got positive results. If those of us responsible for service delivery understood more about which implementation strategies lead to desired outcomes, we could increase the chances of those strategies working every time in similar contexts. This is why many recipes are so precise—it’s not just about the ingredients, but about how they’re prepared, combined, and baked. And if the context changes—say, we move to a higher altitude—we will need to adapt the ingredients and the method so that the recipe works well in the new environment.

In the same way, an off-the-shelf practice model, policy, or other approach that succeeds in one context may not pan out in another. While an intervention needs a strong evidence base to succeed, the program and the manner of implementation also need to fit the culture, values, and daily lives of the community and the people affected by the intervention.

This is where implementation science enters the picture. Implementation science is the study of the factors that lead to uptake, scale, and sustainability of practices, programs, and policies. The purpose of implementation science is to create a bridge between research evidence and the real-world settings of service delivery to improve outcomes for those being served. In its early history, implementation science was focused on the replication and scaling of evidence-based practices.

Over time, the field has evolved, and implementation science is now used much more broadly than its early practitioners originally intended. Likewise, it has struggled to address contextual barriers, with the consequence of perpetuating disparities. One example of this difficulty arises from how the field considers “readiness.” Readiness typically refers to an organization or community’s ability to implement something but does not consider the extent to which researchers, developers, or funders are ready to support implementation by acknowledging a community’s culture, values, and history. This reveals a power divide between implementers and communities, which has implications for how change efforts unfold.

Implementation science has failed to advance strategies that address equity, which represents a huge gap in the field. Implementation science includes both research and practice, and much of implementation research is divorced from the real-world challenges of implementation practice. Despite the field’s attention to evidence-based practices, fidelity, replication, and scaling strategies, implementation support practitioners are not seeing equitable access to interventions or equitable outcomes for service recipients. There are several reasons for this disconnect: Community members are not routinely invited to develop or select interventions that are intended for them; power dynamics between funders and community members hamper authentic engagement with residents; and structural racism and other forms of oppression, such as transphobia and ableism, are not explicitly acknowledged as part of the context in which interventions are being implemented.

Implementation science has the potential to advance equity in both access and service delivery to ensure people and communities get what they need to improve their well-being. However, the research is thin on how to use implementation science to advance equity. Here equity must be distinguished from equality: Whereas equity is the state, quality, or ideal of being just, impartial, and fair, equality aims to ensure everyone has the same amount of something (food, medicine, opportunity). But equality in this sense falls short of equity: If everyone receives a four-foot ladder to reach a 10-foot platform, those under six feet tall may not be able to climb up to it.1 To be achieved and sustained, equity needs to be thought of as a structural and systemic concept. It ensures that each of us gets what we need to survive or succeed—access to opportunity, networks, resources, and supports—based on where we are and where we want to go.

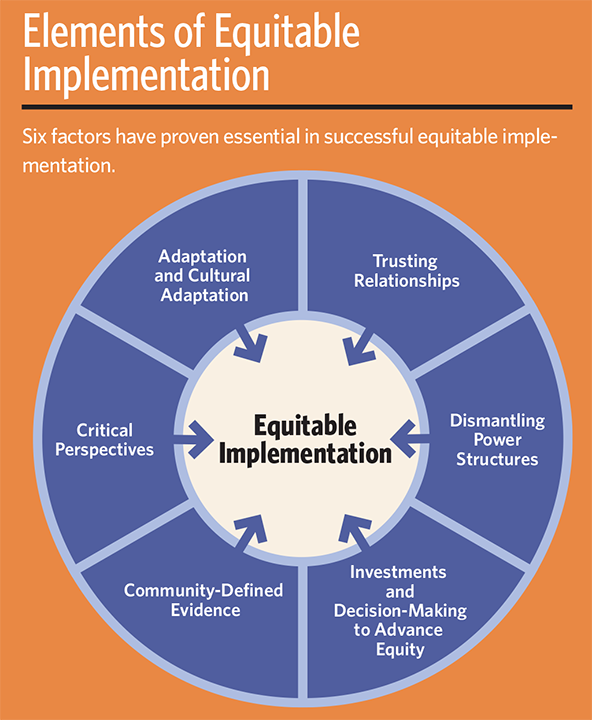

We propose a new lens we call equitable implementation: an explicit and intentional integration of implementation science and equity that attends to what is being delivered, for whom, and under what conditions; and how delivery should be tailored to best meet the needs of the focus population. Equitable implementation occurs when strong equity components—including explicit attention to the culture, history, values, assets, and needs of the community—are integrated into the principles, strategies, frameworks, and tools of implementation science.

Facets of Equitable Implementation

Specifically, we believe there are five crucial elements to equitable implementation.

1. Design and select interventions with implementation in mind.

- Examine community realities from the outset, along with root causes of the needs and barriers an intervention seeks to address, including historical and structural racism.

- Involve the people with the most at stake in the program in selecting programs, policies, and approaches that will be relevant to their communities.

2. Focus on reach and equity from the very beginning of implementation.

- Consider how many people can access and benefit from interventions, which groups will access and benefit from those interventions, and how those groups may require different strategies and adaptations.

- Identify the barriers that groups who have been oppressed on the basis of race and ethnicity, immigration status, socioeconomics, sexual orientation, gender identity, or other characteristics may face in getting access to programs and services and develop explicit strategies to overcome those barriers.

3. Emphasize relationships, engagement, connection, and reciprocity.

- Trust is essential to implementation. But developing trusting relationships takes time, and it requires researchers and funders to show up, listen, trust the community as experts on their lives, recognize and be humble about what they don’t know, be honest and transparent about what they can and will do, and follow through on promises.

- Understand what implementation strategies work, for whom, under what conditions, with explicit attention to how historical and structural racism have shaped the implementation context.

- Develop and/or select implementation strategies that explicitly focus on increasing access to services and ensuring equitable outcomes.

- Involve stakeholders in developing the implementation resources needed to sustain the intervention so that equitable outcomes can be realized.

4. Identify and develop adaptations to programs, practices, and policies that respond to needs and strengths of the local community and the groups who can most benefit.

- Assess adaptability of interventions to meet the needs of diverse populations and to fit within the implementation context.

- Cocreate with researchers, developers of interventions, and community members to define the proposed adaptation and accompanying implementation strategy, test assumptions of both the adaptation and implementation strategy, and support continuous improvement of the adaptation and implementation strategy.

5. Develop strategies at the levels of macro, organizational, and local contexts.

- Acknowledge the limitations of existing implementation science strategies, which address contextual factors that exist at the level of organizations or individuals.

- Develop and use implementation strategies that explicitly address issues at the macro (sociopolitical and economic or “outer” context) level, such as structural racism.

The goal of this supplement is to build collective muscle for equitable implementation. The articles that follow provide cases where implementation science was explicitly used to advance equity, and examples of strategies used in and with communities that provide important lessons about equity for the implementation science field. These articles illustrate core elements of equitable implementation used in a variety of programs, practices, and policies. They include:

- Trusting relationships fuel all implementation efforts. The importance of trust between the Children and Youth Cabinet in Providence, Rhode Island, and its community members is illustrated throughout the stages of their partnership.

- Dismantling power structures is critical in equitable implementation. Funders have indisputable power and cannot respond to the needs of communities without acknowledging and redistributing their power and privilege. Engaging youth leaders throughout the development and dissemination of Youth Thrive was central to the success of the initiative.

- Investments and decision-making to advance equity shift from the normal practice of funders bringing in resources, and with that, power. Decisions—large and small—are made throughout implementation. Each decision point provides an opportunity to promote equitable implementation, as well as who to involve, whether to move forward, and what changes may be necessary. The partnership between ArchCity Defenders and Amplify Fund illustrates how strategic and funding decisions emerged from community expertise and belief in the knowledge and insights that come from lived experience in a community.

- Community-defined evidence supports the notion that credible and useful evidence is not the exclusive purview of randomized controlled trials. Programs developed with evidence drawn from practice and community experience are more likely to succeed because they respond specifically to the community’s needs, assets, and history. Both Village of Wisdom and the Bienvenido Program demonstrate the value of generating and using community-defined evidence to develop interventions and accompanying implementation strategies that advance well-being.

- Adaptation and cultural adaptation seek to enhance interventions and implementation strategies based on context. The articles on a cardiovascular health initiative in Chicago and a parenting intervention in Travis County, Texas, both illustrate how shifts in evidence-based practices and accompanying implementation strategies improved access and uptake, so that everyone who can benefit from an intervention actually receives the intervention.

- Finally, the critical perspectives on implementation science article encourages us all to interrogate how we currently implement interventions and services and to explore why we aren’t getting the results we seek. The article offers three calls to action to change common implementation practices in service of equitable outcomes.

These articles show that the elements of equitable implementation are interrelated. It’s not possible to share power without trusting relationships. Community-defined evidence and cultural adaptations depend on engaging those most affected by interventions from start to finish. These articles also reveal that this work is hard. Departing from business-as-usual takes time, effort, and a willingness to learn new ways of work. We hope this supplement serves as both a call to action for equitable implementation and proof that it can be done.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Audrey Loper, Beadsie Woo & Allison Metz.