(Illustration by Lisk Feng)

(Illustration by Lisk Feng)

When looking across the major social-change efforts of our time, the parabola of success sometimes arcs suddenly and steeply. Take, for example, the precipitous breakthrough in the global effort to eliminate malaria. Beginning in 1980, malaria’s worldwide death toll rose at a remorseless 3 percent annual rate. In 2004 alone, the pandemic claimed more than 1.8 million lives. Then, starting in 2005 and continuing over the next 10 years, worldwide deaths from malaria dropped by an astonishing 75 percent—one of the most remarkable inflection points in the history of global health.

Many events helped reverse malaria deaths, including the widespread distribution of insecticidal nets. Behind the scenes, though, the intermediary Roll Back Malaria (RBM) Partnership played a critical role in orchestrating the efforts of many actors. RBM, founded in 1998, has never treated a patient; nor has it delivered a single bed net or can of insecticide. Rather, RBM has worked across the field of malaria eradication by helping to build public awareness, aggregate and share technical information with a system of global stakeholders, and mobilize funding.

Since 2000, such collaboration has saved more than six million lives. This is not to suggest that RBM is primarily responsible for these dramatic results. But the evidence indicates that by building a marketplace for ideas and a framework for action, RBM helped position the field for breakthrough success.

“RBM has been a clearinghouse, a cheerleader, and a technical adviser for the community working on malaria elimination,” says David Bowen, former deputy director for global health policy and advocacy at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “RBM’s partnership has been very, very helpful to smaller groups and funders—not in providing funding but in linking resources together.”

Funders and nonprofits increasingly recognize that no single organization or strategy, regardless of how large or successful it may be, can solve a complex social challenge at scale. Instead, organizations need to work collaboratively to tackle pressing social problems. Enter a type of intermediary built to serve as a hub for spokes of advocacy and action, and roll all stakeholders toward a defined goal—an intermediary like RBM. These “field catalysts,” which fit into an emergent typology of field-building intermediaries, help stakeholders summon sufficient throw-weight to propel a field up and over the tipping point to sweeping change.

The Role of Field Builders

A decade ago, The James Irvine Foundation asked The Bridgespan Group to investigate what it takes to galvanize the systems-change efforts of disparate stakeholders working on the same problem and focused on attaining measurable, population-level change in a given field.

Building on more than 60 interviews with leaders in the field of education, Bridgespan and the Irvine Foundation produced a report in 2009, “The Strong Field Framework,”1 that spotlighted five components that make for a truly robust field: a shared identity that’s anchored on the field; standards of codified practices; a knowledge base built on credible research; leadership and grassroots support that advances the field; and sufficient funding and supportive policies.

Seven years after we published the report, we found funders still grappling with what it takes to build a strong field. And nonprofits still wondered whether they should venture beyond delivering a direct service and spin out an intermediary that works through other actors to achieve far-reaching social goals.2 Their questions pushed us to better understand what it takes to achieve population-level change, and to look at the roles that field-building intermediaries might play in the process.

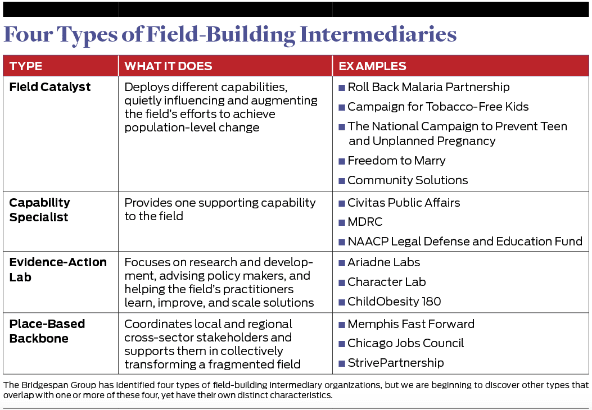

We already knew that such field-building intermediaries came in at least three flavors. (See “Emerging Taxonomy of Field-Building Intermediaries” below.)

- “Capability specialists,” which provide the field with one type of supporting expertise. For example, our own organization, The Bridgespan Group, was founded as a capability builder, with a goal of strengthening management and leadership across the social sector.

- “Place-based backbones,” the mainstays of collective impact, which connect regional stakeholders and collaborate with them to move the needle. One example, Strive Partnership, was founded to knit together business, government, nonprofits, and funders in Cincinnati to improve education outcomes for kids from cradle to college (described in a seminal Stanford Social Innovation Review article in 2011).3

- “Evidence-action labs,” which take on a range of functions to help stakeholders scale up evidence-based solutions. Two examples are Ariadne Labs, which aims to create scalable solutions for serious illness care, and Character Lab, which works to advance the science and practice of character development in children.

Field Catalysts

In late 2016, we surveyed 15 fields that aimed to achieve population-level change. We uncovered a fourth type of intermediary: the field catalyst, which sought to help multiple actors achieve a shared, sweeping goal.4 It is a cousin to the other types of intermediaries, and it’s likely been around unnamed for decades. (Consider the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s role in achieving civil rights victories, for example.)

To be sure, not all change requires a field catalyst. At times, a single entity takes off and tips an entire field. Sesame Street, for example, took the field of early childhood education to global scale and dramatically influenced the growth of evidence-based, educational TV programming for preschoolers. (Think Blue’s Clues or Barney & Friends.)5 But the Sesame Streets of the world, in our experience and research, are rare.

Field catalysts, on the other hand, are not uncommon. They share four characteristics:

- Focus on achieving population-level change, not simply on scaling up an organization or intervention.

- Influence the direct actions of others, rather than acting directly themselves.

- Concentrate on getting things done, not on building consensus.

- Are built to win, not to last.

We also found that field catalysts often prefer that their role go undetected. They function much the way that Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” works in the private sector, where the indirect actions of many players ultimately benefit society. Catalysts usually stay out of the public eye, working in subtle ways to augment the efforts of other actors as they push toward an expansive goal. (If they were to seek the spotlight, stakeholders might view them as competitors and they would lose their influence.) Sometimes, their unseen efforts go unrealized.

Out of the 15 fields that we examined, four are still working to achieve population-level change and three fields are emerging. However, we identified eight fields that did produce momentous change. In each case, field catalysts were a common denominator. That’s not to say they are the only factor of influence. But the consistency of their presence is striking. Indeed, in each of the eight fields that did exhibit significant progress, a catalyst emerged near a sharp inflection point.

There were three fields in particular where catalysts played a critical role. (See “Galvanizing Population-Level Change” below.) The first was achieving marriage equality. In 2002, not a single state issued marriage licenses to same-sex couples. In 2010, a catalyst called Freedom to Marry expanded its scope to include the entire field. That same year, the number of states banning same-sex marriage peaked at 41. Over the next five years, the marriage-equality movement gathered momentum. Thirty-seven states had issued licenses by 2015, when the Supreme Court cleared the way for same-sex couples to marry in all 50 states.

The second field was cutting teen smoking. In the 1990s, high school-age smoking rates climbed to nearly 37 percent. The Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids came to life in 1995, with the explicit goal of driving down youth smoking rates. Two years later, US rates began a year-over-year decline to 9.2 percent by 2014.

The third field where catalysts played a critical role was reducing teen pregnancies. In the late 1980s, teen childbearing in the United States began to rise from a rate of 50 births per 1,000 teenagers to more than 60 births per 1,000 in 1991. With its founding in 1996, the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy mobilized public messaging efforts by partnering with entertainment media and faith communities. Following a slight uptick from 2005 to 2007, the birth rate dropped to 20 births per 1,000 in 2016.

These three catalysts, and five of the other highly effective ones we identified, range widely in size—with annual budgets of between $4 million and $73 million6—but all punch far above their weight. To be sure, neither do they deserve all the credit for their fields’ success, nor would they claim it. As the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids’ founder, Bill Novelli, puts it, others “have been laboring in these vineyards for many years.”

And yet, again and again in our study, field catalysts correlated with the tipping point for change. These catalytic intermediaries may be playing an outsized role in systems-change efforts. Bridgespan recently interviewed 25 social sector leaders to ascertain what they believed were the most influential ideas over the past five years. “Systems approaches to solve large, complex problems” ranked among the top handful. As more and more actors engage in systems change and name it as their goal, perhaps it’s not surprising that catalytic intermediaries begin to surface.

Regardless of how a field catalyst comes to life, it will likely encounter some unique tests, including: earning the trust of funders and direct-service providers, developing a deep understanding of how change happens, and staying nimble enough to fulfill the field’s evolving needs. If a catalyst is to surmount obstacles both known and unknown, it will have to think through a set of deliberate choices and build discrete skills.

What Field Catalysts Think About

Field catalysts are very intentional in what they choose to think about, and they think differently from most other social-change organizations in three important ways.

First, they think about how their field—fractured and fragmented though it may be—can achieve population-level change. Catalysts don’t concern themselves with building an organization or scaling an intervention. As the business management author Jim Collins put it in another context, they focus on achieving a “big hairy audacious goal,”7 such as eradicating polio or ending chronic homelessness. Rather than jump to “the answer,” field catalysts first ask, “What’s the problem we’re trying to solve? And have the stakeholders we want to work with clearly defined it?”

In a TEDx talk on systems change, philanthropist and advisor Jeffrey Walker mused, “Not knowing everything is a skill.”8 Approaching a complex, system-sized challenge can require a “beginner’s mind … where you rebuild what you know and what stakeholders know into a common vision.” Catalysts define the vision, or mission, in a way that’s bold enough for stakeholders to rally around, yet specific enough to make a measurable difference.

When Dr. Jim Krieger, formerly chief of the Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention Section of Seattle’s Department of Public Health, first thought about taking on a catalytic role in preventing obesity, he knew it was a problem that mattered: The percentage of obese children in the United States has more than tripled since the 1970s. Yet a mission to “reduce obesity” would have been too vague. It took lots of conversations with many stakeholders in the public health arena and a review of the evidence on what worked for Krieger to focus on nutrition and address the upstream food environment that shapes people’s food choices. What proved a rallying cause: reduce consumption of the excessive amounts of added sugar marketed to Americans. Krieger’s 2016 response, the creation of Healthy Food America, is now a linchpin in the movement to slash the 76 pounds of added sugar that Americans consume every year.

Second, field catalysts think about a road map for change. Even as they define a mission, catalysts identify organizations that are already working on promising solutions. Catalysts delineate the field’s topography, tracing the links between funders, nonprofits, NGOs, governmental institutions, for-profits, community networks, and other stakeholders that matter. In this way, the catalyst begins to plot a long-range map for advancing a common goal.

In 2003, when Freedom to Marry (FTM) joined a wide-ranging campaign to achieve marriage equality, it was a “behind-the-scenes cajoler and convener … an adviser to funders”9—and not much more. But two years later, with additional states banning same-sex marriage, FTM took on a catalytic role. It led the development of a strategic road map for achieving a transformative, measurable goal within 15 to 25 years: nationwide marriage for same-sex couples.

FTM helped convene leaders from 10 LGBT organizations to draft a road map, “Winning Marriage: What We Need to Do.” The strategy centered on an intermediate, achievable goal, dubbed 10/10/10/20: In 15 years, ensure that 10 states guarantee marriage protection; 10 states have “all but” marriage protection such as civil unions; 10 states at least have more limited protections such as domestic-partnership laws; and 20 states have experienced “climate change” in attitudes toward LGBT people. The map laid out tactics for rolling out the plan, as well as guiding principles for reaching all 50 US states.

As conditions change, catalysts and their allies make mid-course corrections. In its first iteration, the Winning Marriage road map wasn’t enough to navigate past a determined opposition in California (that is, the looming Proposition 8 ballot initiative). But it did define a collaborative model for achieving vividly defined goals, which would eventually ladder up to breakthrough change. In fact, of our eight most successful catalysts, the majority created strategy road maps to clarify critical challenges and identify steps for getting to success.

The third thing that field catalysts think about is what it will take to marshal stakeholders’ efforts. Field catalysts make a calculated choice to serve rather than lead. Effective leaders of field catalysts often possess what Jim Collins, in Good to Great, calls “Level 5 leadership,” or the “paradoxical blend of personal humility and professional will.”10 It requires deliberately subjugating ego while summoning the grit to keep pushing past inevitable setbacks. As one leader of a field catalyst put it, “Part of the work of engaging the hearts and minds of others comes down to influence whispering and not being viewed as the causal part of change.”

When Community Solutions launched the 100,000 Homes Campaign—a national movement to find permanent homes for 100,000 chronically homeless Americans—the organization’s president, Rosanne Haggerty, made clear that “the campaign was more important than any one organization.” However, fostering “an ethos of humility” was not so easy.

Early in the campaign, Haggerty’s team successfully pitched a story on a national evening news broadcast to draw attention to solutions to chronic homelessness. But the piece ended up casting Community Solutions as the hero, depriving local organizations of primary recognition for their work. “We learned the hard way that the media wasn’t used to telling this new kind of story, in which there are many heroes, not just one,” says Jake Maguire, who ran the campaign’s communications strategy. “We created a new policy: If we had to choose between Community Solutions or a participating organization being mentioned in a news story, we’d choose the local organization.”

By deflecting credit, catalysts build sufficient credibility to attract other stakeholders. To take the next step—rally direct-service providers—catalysts think about how they can direct funding to the field. It’s a compelling challenge, given that intermediaries like field catalysts typically lack the power of the purse. But the evidence shows that catalysts can unlock pools of previously unavailable capital. A common approach: collect, analyze, and share data that surfaces high-potential investment opportunities. Such was the case with the 100,000 Homes Campaign.

The federal government—and to a lesser extent, philanthropists—controlled the resources for housing the chronically homeless, not Community Solutions. As Haggerty saw it, the big challenge was to steer those resources to individuals who could best benefit. Her team created the Vulnerability Index, a data-rich tool for triaging homeless individuals, based on their health. For the first time, health indicators told communities who was most at risk of dying in the street. If, say, an individual had three hospital visits in the past year, the index would prioritize a “prescription” for an apartment or studio. This innovative tool helped Community Solutions steer funding streams, even though it didn’t control them.

Community Solutions took a similar approach to working with 186 US communities, by equipping them with data and challenging them to meet a measurable goal: house 2.5 percent of the chronically homeless population every month. “Clear goals helped us realign resources and, in some cases, attract new funding,” says Haggerty. The result: Within four years, the 100,000 Homes Campaign lived up to its name.

This is not to suggest that intermediaries should use Community Solutions as a blueprint for change. Each aspiring catalyst will have to define its own approach to galvanizing its field. However, by charting local players’ progress toward the 100,000 stretch goal and making performance data transparent, Community Solutions helped build momentum and unlock sufficient capital to drive breakthrough change.

What Field Catalysts Do

To be sure, it’s not easy to differentiate between how catalysts think and how they act. As with all change efforts, there’s the decisive moment when the learning, mapping, convening, and strategizing shifts to all-out execution. Field catalysts that succeed in channeling the efforts of disparate stakeholders toward transformative change do three things well.

The first thing catalysts do well is to help the field meet its evolving needs by filling key “capability gaps” across a range of disciplines. As the field evolves and new needs emerge, it’s often the catalyst that must identify and fill the voids in the field’s skill sets. Thus, catalysts’ roles span traditional organizational boundaries: They conduct research; build public awareness; assess the field’s strengths and weaknesses; advance policy; contribute technical support to direct-service providers; collect, analyze, and share data; and more.

Such is the case with the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy (National Campaign), which has helped stakeholders view teen pregnancy through a child-welfare lens rather than a moral one. The National Campaign uses data, not dogma, to demonstrate that by preventing teen pregnancies, society can head off other serious problems, such as child poverty, abuse, and neglect. The National Campaign has taken on an array of jobs to be done, including the following:

- Making the media an ally. The National Campaign has worked as a behind-the-scenes adviser on MTV’s wildly popular 16 and Pregnant, which is credited with reducing teen births by 5.7 percent during the 18 months following the show’s premiere.

- Creating relevant resources for teens. In 2013, the National Campaign launched Bedsider.org, a “dive straight into the details” information hub for learning about every available birth control method.

- Building bridges to communities of color. With support from the social impact agency Values Partnerships and prominent faith leaders nationwide, the National Campaign created an online tool kit to help the leaders of black churches talk about teen and unplanned pregnancy with their congregations.

- Assembling and sharing knowledge. An assessment by McKinsey & Company concluded that the National Campaign is the nation’s leading resource on preventing teen pregnancy.

- Mobilizing funding for the field. In 2015, the National Campaign played a crucial role in “securing and maintaining $175 million annually in federal investments for evidence-based teen pregnancy programs.”11

An effective catalyst doesn’t have to possess a deep expertise in all of these areas. But if the catalyst can fill critical capability gaps, it just might build the kind of momentum that has enabled the field of reproductive health to drive the teen pregnancy rate in this country to a historic low.

The second thing that field catalysts do well is that they appeal to multiple funders. Organizations that help galvanize breakthrough change earn credibility and win enough trust to influence the field’s other actors. Those two characteristics seem to be nonnegotiable. As we’ve seen, one of the surest signs that a field catalyst is credible is that it steers funding streams without controlling them, as Community Solutions has done. For its own funding, a field catalyst purposely taps into several sources.

When a catalyst sets out, it can be tempting to rely primarily on a single funder. But that might be a mistake. Catalysts earn permission to support other stakeholders by proving that they serve the interests of the entire field. By securing multiple funding sources, they demonstrate that they aren’t beholden to any single player. Among high-achieving catalysts, their top two sources comprised less than half of the total funding. One such catalyst is the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, which was created by a single philanthropy, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), but soon attracted other funders.

In the 1990s, teen smoking rates climbed from 27 percent to 37 percent. Alarmed at the possibility that half of the nation’s high schoolers might soon be smokers, Steve Schroeder, president of RWJF at the time, asked his board of directors to put substantial money into fighting tobacco. The board agreed, with one stipulation: RWJF would have to bring in other players to support the initiative and, above all, contribute financially. Schroeder recruited the American Cancer Society and the American Heart Association to join RWJF in creating a catalyst called the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. The Cancer Society’s and Heart Association’s financial contributions were small, relative to RWJF’s investment. Nevertheless, the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids’ former CEO, Bill Novelli, argues that having more funders made stakeholders “feel like it was a public health endeavor,” rather than a RWJF initiative.

Today, the Gates Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, United Health Foundation, and the CVS Health Foundation are among the broader group of funders supporting the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. The result is that RWJF’s contributions have amounted to less than half of the organization’s total funding over the past 10 years.12 For the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, funding sources are directly linked to its ability to operate independently and in service of the entire field. Fueled by this broad funding base, the organization played a catalytic role in helping drive the percentage of teen smokers down into the single digits.

A field catalyst can more easily secure funds by forming as an independent, 501(c)3 nonprofit with its own board, as the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids did. This helps push back on the notion that the catalyst is a “funder’s pet project.” Not all successful catalysts come to life as independent entities. But all of those that we reviewed drew on multiple sources of funding.

The third thing field catalysts do well is that they consult with many, but make decisions within a small group. Catalytic field builders work with whomever it takes to solve the problem. Having earned credibility and trust, field catalysts seek input from many but limit decision making to a comparative few. By taking a consultative rather than consensus-driven approach, they can respond quickly to new developments.

Managing the tension between who owns the “D” and who doesn’t is an age-old challenge for cause-based collaborations. According to research from Bain & Company, “Every person added to a decision-making group over seven reduces decision effectiveness by 10 percent.”13 Then again, many initiatives fail to sustain impact because they do not incorporate the input of key constituents. Successful field catalysts strike a balance.

In the early 2000s, Dr. Steven Phillips, who now sits on the boards of Roll Back Malaria and Malaria No More, set out to help his employer, ExxonMobil, understand how it could loosen malaria’s grip on the company’s African workforce. Phillips put much of his focus on RBM, which was regarded as a key pillar in the field. But in Phillips’ view, RBM’s “authority was unclear and its debates were reduced to interminable squabbles between rival aid groups.”14 Phillips raised $3.5 million from ExxonMobil, the Gates Foundation, and others to hire the Boston Consulting Group to improve the organization’s effectiveness.15

Through its engagement with the Boston Consulting Group, RBM established more effective governance structures and processes. This new approach was on display when RBM unveiled its strategic road map: Action and Investment to Defeat Malaria 2016-2030. RBM collected input from around the world and built buy-in. But when it had to, RBM acted independently in crafting the strategy. RBM had the authority to make its own decisions, even as it remained accountable to other players. The tight link between accountability and autonomy gave RBM even more incentive to escape the shackles of momentum-sapping groupthink.

Unlocking Your Field’s Potential

For any organization that’s thinking about launching a field catalyst, the challenges can be intimidating. How do you survey a complex field and spot the white space for breakthrough change? What’s a practical approach to indirectly influencing many direct actors? Shawn Bohen, who is responsible for shaping growth and impact strategies at Year Up, ventured some answers.

Year Up’s direct-service approach to helping employers discover hidden talent has served more than 17,500 young adults—an impressive accomplishment. And yet, “the number of opportunity youth is growing on our watch,” says Bohen. When Year Up launched in 2000, three million young people were out of work and the classroom. Today, that population has doubled.

The core problem became apparent eight years ago, when Year Up changed its mission statement from “bridge the opportunity divide [between youth and employers]” to “close the opportunity divide.” According to Bohen, “The direct service enterprise, by itself, wasn’t going to close the divide. It was ensuring that the activities that all of us were engaged in become the new normal.” In partnership with longtime collaborator Elyse Rosenblum, Bohen persuaded her senior Year Up colleagues to incubate a catalytic intermediary that would work with businesses to build pipelines to the untapped talent pool of opportunity youth.

As a first step, Bohen and Rosenblum’s team probed deeply around questions like: Why is the market for opportunity youth broken? What are the fundamental barriers between supply and demand? Based on those discussions, the team mapped a strategy for coalescing partners around the larger goal of impacting many more lives.

The team’s road map is built around a heuristic dubbed the “three Ps”: perception, which speaks to changing the negative stereotypes around opportunity youth; practice, which builds strategies for getting companies to look past a job candidate’s pedigree and instead focus on her competencies; and public policy, which aims to build incentives for seeding this new talent market. The mapping effort helped Bohen and her allies determine that even as they focused on all three areas, “changing employer, educator, and training practices emerged as the key thing.”

As the team began to unveil its idea, it ran into a problem that probably every direct-service entity faces as it pivots to indirect action. As Bohen puts it, “You’re in the somewhat awkward position of people thinking you’re just self-dealing when you’re talking about the field.”

Their solution was to leave no fingerprints. In 2014, they launched the first initiative from their still-incubating intermediary: a national, multimedia public service campaign called Grads of Life, which seeks to change employers’ perceptions of the millions of young adults who lack access to meaningful career and educational opportunities. The overarching goal: activate a movement, led by employers, to create pathways to careers for opportunity youth nationwide.

After three years, Bohen believes that Grads of Life is quietly gaining traction. The campaign has attracted more than $81 million in donated media, including its own Grads of Life Voice blog on Forbes.com. But Bohen’s optimism is tempered by a stone-cold reality: The sector often conflates scale (via replication) with impact. The result is that catalysts find it challenging to attract funding for truly transformative work, given that replication remains the dominant mind-set for achieving widespread change. “So much of the social sector is still focused on the enterprise as opposed to the game change—transformative impact—which happens through field-catalyst efforts focused on systems change,” says Bohen.

How to head off a dispiriting scenario where, after pouring 20 years of work and resources into a social challenge, “we still have 2 percent market penetration into the problem”? As Bohen sees it, the sector must untangle the knots that have tied scaling to systems influence. To make measurable progress against this century’s emerging challenges, that just might mean summoning the field catalyst’s invisible hand.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Bill Breen, Taz Hussein & Matt Plummer.