(Illustration by Mitch Blunt)

(Illustration by Mitch Blunt)

When Lance Fors first entered the elementary school classroom, he was immediately struck by the unusual level of student and teacher engagement. Animated chatter filled the classroom, and faces bore expressions of extreme concentration and seriousness, as well as the occasional grin. At each desk sat a small child accompanied by an adult, both oblivious to the other pairs around them. All of them were engaged in the same activity—reading.

The reason this classroom was so extraordinary is that it was participating in a program run by Reading Partners, an Oakland, Calif.-based nonprofit that provides one-on-one tutoring for K-6 students living in low-income communities. In twice-weekly sessions lasting 45 minutes, volunteer tutors (everyone from retirees and full-time parents to high school students and working professionals) help young children who often barely know their alphabet start to read books and answer questions about their content.

Reading Partners’ strategy is simple—use volunteers to deliver the type of teaching that underperforming children so badly need yet is unaffordable in the public education system. The results are dramatic—the average student advances an entire grade level in reading skills after just 30 hours of one-on-one tutoring (twice as fast as their peers who are not in the program).

So what was Fors, a man who’d spent his career building companies, doing in a classroom used to promote literacy? Fors was on a site visit organized by Silicon Valley Social Venture Fund (SV2), to learn more about Reading Partners.

SV2 is a type of giving circle—groups of donors who put anything from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars (and in some cases much more) into a pool of funds, teach themselves about effective forms of philanthropy and issue areas, and decide collectively how to allocate their money.

Fors first learned about SV2 while reading “When Givers Get Together,” a BusinessWeek article written by Jessi Hempel that described a form of philanthropy that allowed donors to pool their funds to make a bigger impact and have a say in how their money would be used. Fors was intrigued by the idea of collective giving. He’d recently stepped aside from certain parts of his business and had started thinking about how to make a greater difference in the world.

The problem was that Fors didn’t know much about philanthropy. “I wanted to get really good at how best to give money away in reasonable chunks,” he explains. He also wanted to do more than write checks to organizations with which he had no contact. Most important, he wanted to find a community of like-minded people who could support him as he learned how to become a more effective donor.

After learning more about SV2, he joined the organization in 2005. Rather than learning from a book or a class, SV2 members—called partners—learn from each other. Supported by his colleagues, Fors soon acquired the confidence and experience to assess nonprofits effectively, judge their needs, and recognize their potential to expand and make a bigger difference. “This was a fast track to learning how to make a good grant,” he says. What also struck Fors was the extraordinary camaraderie he found among a group of people working together on meaningful projects. “There’s so much energy created when people get together and get excited about impact,” he says.

Growing in Popularity

Giving circles are a significant and growing segment of US philanthropy. There were about 800 giving circles in 2007 (the latest formal survey).1 A May 2009 study estimated that about 600 giving circles in the United States together gave more than $100 million and engaged more than 12,000 people.2 From these statistics, I estimate that giving circles have granted hundreds of millions of dollars and engaged tens of thousands of people during the last decade.

Giving circles range widely in size, some with only a handful of members and others with several hundred. Although membership has tended to be largely female (about 53 percent were all-female in 2006), they’re increasingly mixed or all-male (according to the Giving Circles Network).3 Giving circles are formed by former classmates, members of the same place of worship, or simply friends, work colleagues, or neighbors who like spending time together but want to do that more productively. Participants span all ages, professions, religions, ethnicities, and income levels.

The structure of giving circles varies tremendously. Some are small, informal groups that share volunteer activities and decision making. Others are large and employ staff to manage finances and administration. Some are housed in philanthropic institutions. Others are membership organizations, independent nonprofits with membership fees and minimum donation amounts. Many offer volunteering opportunities, either in helping run the giving circle or working with the nonprofits the circle funds.

In spite of these variations, giving circles all share the same philosophy—that by working collectively, donors can do more with less and find new ways to give more strategically and accountably, and with measurable impact. Giving circles expose members to best practices and learning through doing. They help individual givers to become proactive rather than reactive, and to practice structured rather than informal giving. And because donors base their giving on research, education, collective decisions, and—when housed at philanthropic institutions or run by professional staff—the experience of professional grantmakers, giving circles help turn intent into impact.

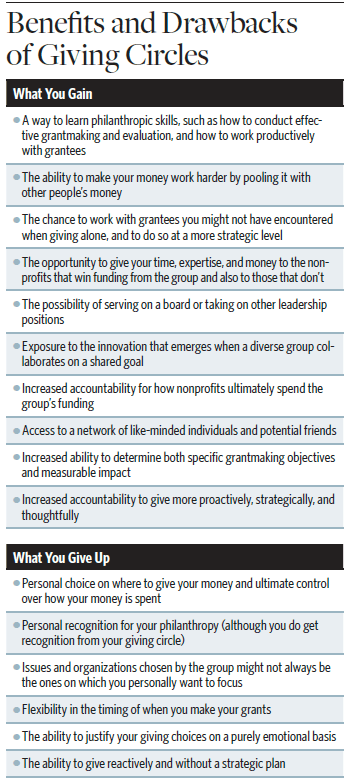

For donors with no philanthropic staff or access to professional giving advice (the vast majority of givers), this kind of support is critical. Between the signing of a check and the delivery of vaccinations to an impoverished family in Liberia or a better education for low-income sixth-graders in Detroit lie a complex set of decisions, strategies, and infrastructure, all of which contribute to the impact of the money itself. As more people recognize the challenges involved in making thoughtful and effective giving decisions, they are turning to giving circles and other forms of collective giving. (See “Benefits and Drawbacks of Giving Circles” below.)

A Gap in the Market

My interest in collective giving was born in the 1990s. It was a thrilling time. The Internet was opening up new opportunities for connecting, communicating, and making transactions. I was studying for my MBA, and most of my classmates at the Stanford Graduate School of Business were writing business plans for dot-com startups. Like them, I had a burning desire to create my own enterprise. But I wanted to do something different. Instead of establishing an organization designed to make money, I wanted to create one that would give it away.

At the time, many technology companies in Silicon Valley were going public, creating thousands of instant millionaires. I figured that these young, energetic, and highly entrepreneurial people would be attracted to a form of philanthropy that treated social investments with the same seriousness, accountability, and efficiency as for-profit investments. I felt sure that, as it was for me, these people wanted to do more than write checks. They wanted to learn from their peers and work in partnership with nonprofits. I had spotted a gap in the market—and I knew how I could help fill it.

In 1998 I founded SV2. It turns out that I was not the only one with this idea. Although I didn’t know it at the time, a similar model had just been created in Seattle (where Microsoft had spawned its own technology-driven community) when Paul Brainerd founded Social Venture Partners Seattle. Cultural shifts were sweeping through the philanthropic sector—driven partly by these young, self-made wealthy individuals—and entrepreneurial vehicles were emerging to support the higher level of accountability demanded by the new economy’s social investment dollars. “Giving while living” became the new norm.

Among these new types of organizations was SV2. Our pooled funds provide multiyear, organizational capacity-building grants to nonprofits, helping these organizations build up their business infrastructure to operate more effectively and efficiently. SV2 partners (who come from a wide range of professions, age groups, social passions, and backgrounds) are the decision makers when it comes to allocating funds to nonprofits. Every partner—regardless of the size of his or her gift—has an equal vote, and new partners can participate immediately in grantmaking.

Nonprofits—by invitation or by responding to an open request for proposals—present their case to the partners, who assess their needs, their potential to grow, and the impact they might be able to have through additional funding, management support, and access to partners’ expertise and networks. Together with the grantee, SV2 partners develop grant contracts that include the strategy, implementation plans, and quarterly performance benchmarks needed for the nonprofit to achieve its goals. Although grantees are accountable to SV2 to meet and report on these goals, SV2 is responsible for helping achieve them by investing partners’ time and expertise in addition to money.

Partners help grantees not only to build the capacity needed to achieve current goals but also to come up with new, more ambitious goals and strategic growth plans. Several partners have joined grantees’ boards, and in a few cases even chaired them. Many partners make individual gifts to nonprofits in addition to their SV2 grant. In the past year alone, SV2 partners have collectively given an additional $744,800 and 1,245 hours of volunteer time to past and present grantees.

Getting Together to Give

Collective giving organizations are part of a dynamic new era for philanthropy—one in which donors are becoming far more involved in their giving. Many donors no longer want to give in isolation—they want to get together to share their ideas and excitement. They want to talk to others about philanthropy, to compare experiences and problems, and to ask basic questions among communities of people they trust. And although there is a great deal of variation among giving circles, they share important characteristics that distinguish them from other types of philanthropy.

It starts with the bringing together of money and talent. “Everyone puts in a certain amount of money and when we pool that, we end up with the ability to invest in a whole range of nonprofits and with a lot more funding than the partners could give individually,” says Paul Shoemaker, executive director of Social Venture Partners Seattle. “It’s the same reason anyone invests in a mutual fund.”

By pooling money, donors can have a bigger impact on a nonprofit. And giving circles do more than gather financial assets. They also draw on members’ skills and knowledge. Those who’ve worked with startup companies, for example, might become more involved with an organization at the early stage of its development. The skills of a human resources or management professional could be valuable at a later stage in the organization’s evolution. Members also provide tremendous support to grantees as coaches, advocates, and network builders—not to mention the stamp of credibility that a giving circle investment can provide the organizations it funds.

Shoemaker believes the hands-on nature of this type of giving is part of its power—particularly since it helps partners to expand their own capabilities. “There’s nothing like experiential learning,” he says. “When you do a strategic plan or a marketing strategy for a nonprofit you learn a huge amount—you can’t put a price tag on that.”

Moreover, when people donate collectively they end up giving more, and more effectively, than they do alone. In 2011, more than 71 percent of the SV2 partners surveyed said they were giving larger amounts of money now than before joining the organization, with nearly 90 percent reporting that their giving had become more strategic.

Finally, as Fors experienced, partners are often pleasantly surprised to find the extraordinary camaraderie generated by a giving partnership. Joining forces on shared goals and meaningful projects is a way of bonding with a group of people who are happy and enthusiastic about their work. Half the fun of being part of a philanthropic partnership is being around an energetic, intelligent, and engaged group of people. In the process, people often develop what turn out to be deep and lasting friendships.

Giving Circles Vary

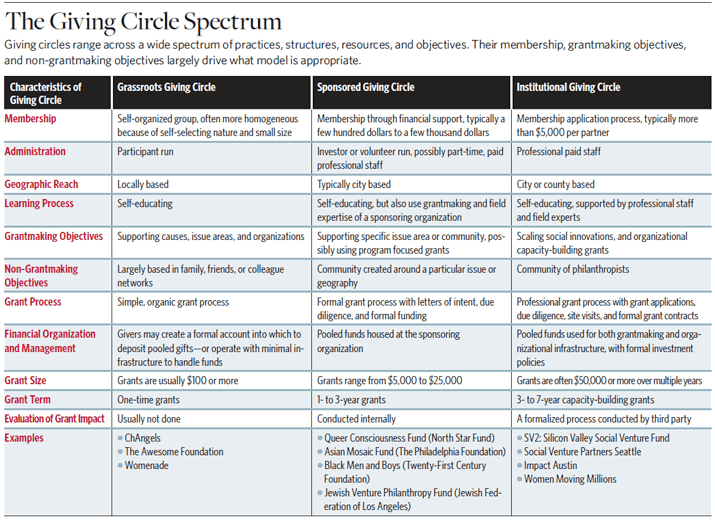

There are three basic types of giving circles: grassroots giving circles, sponsored giving circles, and institutional giving circles. (For a comparison of the characteristics of these three types of giving circles, see “The Giving Circle Spectrum” below.)

At one end of the spectrum are grassroots giving circles—informal, self-directed giving circles in which small groups of people (who often already know one another) come together for the purpose of giving. ChAngels, a group based in Northern California that was started by a 9-year-old girl named Kate, is an example of a grassroots giving circle. It has nine members, mothers and daughters from the same school who come together to research ideas for projects, which they present at monthly meetings, and collect and earn spare change (hence the name ChAngels). They volunteer at nonprofits, join walkathons, and run small-scale fundraising activities for causes such as relief for Japanese tsunami victims, books for Fijian libraries, and a small farm where sick children can play with animals. On its blog, members share information about their activities, such as a Popsicles and Pillowcases Party during which girls get together to transform pillowcases into dresses delivered to girls in need through the Dress a Girl Around the World program. The simplicity of the ChAngels model makes it easily replicable by any mother-daughter group in any community.

At the other end of the spectrum are institutional giving circles, independent nonprofits that have formalized the giving circle model into a structure similar to a grantmaking intermediary. These circles have professional staff, formalized membership and grantmaking processes, and a significant donor base (whose contributions fund both the circle’s grantmaking and its infrastructure). An example of this type of circle is Impact Austin, which was founded in Austin, Texas, by Rebecca Powers in 2003 and has spread to Indianapolis, San Antonio, Pensacola, Fla., and other cities. More than 4,000 women each give $1,000 a year through Impact Austin, and each has an equal voice in selecting recipients for grants. By 2010, the organization had made more than $2.6 million in grants to nonprofits supporting a range of causes, such as job training and community ballet instruction, as well as after-school programs and health care for uninsured and underinsured people. Members of Impact Austin also help run the grantmaking organization. The group uses volunteer management software to fit the right member with the right volunteer task. Sometimes, members work directly with the nonprofits they fund or participate in their advocacy initiatives. Believing in the importance of empowering women to realize their philanthropic potential, Impact Austin also has a program called Girls Giving Grants in which young women in grades eight through 12 each contribute $100 and participate in collective grantmaking.

In the middle of the spectrum are sponsored giving circles—groups that have formalized their collaboration and housed it within an existing philanthropic institution, such as a community foundation. These giving circles use the infrastructure and expertise of an existing philanthropic organization, but remain donor led (though they may have part-time professional staff). An example of this type of circle is the Queer Consciousness Fund (QCF), a donor-advised fund of the North Star Fund. Founded by Craig Harwood, Terrence Meck, and Reid Williams—and tapping into the expertise of their mutual friend, Weston Milliken, co-founder of the Queer Youth Fund—this giving circle was established to give money to the GLBTQQI community (gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals, as well as those who identify themselves as queer and those questioning their sexuality and intersex individuals). Members of QCF each contribute $25,000. QCF supports organizations in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania. Past grants have included funding organizations such as Spring Clearance (which runs an annual weekend retreat to promote well-being, healing, service, and community engagement among GLBTQQI people recovering from crystal meth addiction) and Trans in Action (which supports runaway and homeless transgender and gender-nonconforming young people).

Over time, the structure of any particular giving circle may evolve, from grassroots to sponsored, or from sponsored to institutional. When SV2 was created it was essentially a sponsored giving circle, with a donor-advised fund at the Community Foundation of Silicon Valley (now Silicon Valley Community Foundation). After expanding our partner base, grantmaking portfolio, and organizational vision, we decided that becoming an institutional giving circle, with our own nonprofit grantmaking organization, would be a more effective structure through which to maintain our entrepreneurial culture and ability to innovate.

Some institutional giving circles have even gone global. Social Venture Partners Seattle, for example, has inspired a global network of affiliated organizations called Social Venture Partnership International, which has 25 affiliates in the United States, Canada, and Japan with members all contributing passion, knowledge, time, and experience, as well as money.

Starting Your Own Circle

One of the great things about giving circles is that it takes only a few people, a shared passion, and a philanthropic purpose to create one. You can even use an existing group—such as a book club, investment club, or religious group—as the foundation for a giving circle. Although giving circles are easy to start, without careful planning one can easily lose its focus. (For more information on how to start and evolve a giving circle, see www.giving2.com).

Once the members of the giving circle have been selected, the first thing to do is to decide on the group’s mission and what its funding focus will be. How are you going to give away the funds the group collects? Should your giving circle, for example, decide what to fund on the basis of discussions among the members and members’ research? Will you allow nonprofits to submit applications for funding? How will you conduct due diligence on the nonprofits you’re considering investing in and verify that gifts will be used as intended? (This is particularly important for larger-sized gifts.) Will the group require a unanimous decision on whom to fund? Will members conduct site visits of the nonprofits it funds? And what kind of feedback will beneficiaries be required to submit on how the group’s money has been spent and what difference it’s made?

Members also need to establish the size or range of each member’s financial contribution. In groups where every member has an equal say in how the money is distributed, it often makes sense for everyone to give the same amount. Some groups have tiered donation levels. To manage the money, you can set up a joint bank account, establish a donor-advised fund at a community foundation or an investment company, or even create a public charity.

Giving circle members also need to decide whether or not the group can expand and how big it’s going to become. Are you going to request that members make a yearlong commitment? Can donors join at any time, or should they be allowed to sign up only at certain times of the year? Some giving circles prefer to keep the group intimate, restricting membership to the small group of people that first came together. In other cases, organizations grow rapidly and become significant forces for change.

A giving circle also needs to be prepared to learn and grow. What happens when members disagree on a voting decision, when a grantee fails to meet expectations, or when members’ interests shift over time? Setting up parameters for dealing with such challenges in advance can promote group cohesion and effectiveness. Through successes and challenges, giving circles should be forums for shared social objectives and be safe spaces in which people can engage in group learning, idea generation, and grantmaking. It is important to remember that even unsuccessful grants can be successful learning experiences and provide an opportunity to do things better in the future.

The Power of Collective Giving

Since becoming a grantee of SV2, Reading Partners has expanded rapidly. It now operates in 36 schools and serves more than 17,000 students. The ability to scale up a philanthropic enterprise like Reading Partners is critical. “In California about one in three fourth-graders can read at their grade level and nationwide it’s only slightly higher, so we’re talking about the vast majority of children throughout the country being unable to read at their grade level,” says Michael Lombardo, CEO of Reading Partners.

Lombardo believes that the support of an organization like SV2—which brings skilled, knowledgeable, and highly engaged donors along with funds—has been important in helping Reading Partners grow. “It gives an organization like ours a disposition to be bold,” he says. “It’s about taking risks and trying to do what seems to be impossible.”

Reading Partners isn’t the only one that has benefited from the relationship. Involvement in the program gave Fors a huge philanthropic learning opportunity. Working with grantees has taken him from high-energy classrooms to chaotic startups where social entrepreneurs compensate for their lack of organizational capacity with their excitement and enthusiasm. After months of volunteering his time and expertise, Fors created a strategic plan for Reading Partners based on a visionary growth plan. After presenting the strategic plan to the Reading Partners board, Fors joined the board, and he is now its chairman. Since retiring from his last company, Fors has become a full-time, high-engagement philanthropist, chairing the boards of Reading Partners, New Teacher Center, Social Venture Partners International, and SV2.

“For me, getting involved in this way was the beginning of seeing the potential leverage you can get from this kind of work,” says Fors. He also loves collaborating with nonprofit leaders and spending time with his venture philanthropy partners. “You’re developing a much deeper network of friends because you share this profound common value,” says Fors.

Philanthropy begins with the heart. It’s an expression of our love for humankind. Yet love is not always enough. To tackle the huge, complicated problems affecting the lives of those around us, we need the support of others. We need to do more with less, channeling precious philanthropic resources into innovative ways of giving—learning constantly, partnering with others, pooling funds, and generating new ideas by sharing our knowledge and experience. Getting together to give—whatever the membership size, collective giving level, structure, or purpose of the organization—is a powerful way to transform the world while also transforming your giving.

This article is based in part on the book Giving 2.0: Transform Your Giving and Our World, by Laura Arrillaga-Andreessen (Jossey-Bass, 2011).

Laura Arrillaga-Andreessen is a lecturer in philanthropy at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and founder and advisory board chairman of Stanford University’s Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society (PACS). She is the founder and chairman emerita of Silicon Valley Social Venture Fund (SV2), president of the Marc and Laura Andreessen Foundation, and a director of the Arrillaga and Sand Hill foundations. She is the author of Giving 2.0: Transform Your Giving and Our World (Jossey-Bass).

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Laura Arrillaga-Andreessen.