(Photo by iStock/Orbon Alija)

(Photo by iStock/Orbon Alija)

In previous essays, we’ve discussed how powerful stories can motivate people of different backgrounds to care about and engage with large and complex challenges like reversing climate change or social injustice. But that’s only part of the equation. Once they’re inspired, you need to get them to act.

NGO and nonprofit calls to action are often an afterthought. Many organizations spend big money on producing engaging stories and events, then find themselves scrambling last-minute for what to ask people to do. What’s more, it can be hard to distinguish social change goals from calls to action. As a result, calls to action sometimes feel too small and disconnected from the problem (“Want to fix climate change? Follow us on social media”) or too big and ambiguous for any one person to take on (“Stand up for the climate”).

The following four principles, rooted in social science and best practice, can help organizations design effective, “just right” calls to action that can drive real change.

1. Make It Specific

The most effective calls to action aren’t one size fits all. They focus on a target audience and translate the overarching goal into a specific, observable behavior that the audience can adopt. Abstract calls to action can leave people discouraged and stressed. Abstraction often means the burden of identifying a particular action falls on the individual, and too many choices can be overwhelming. Specific calls to action, by contrast, increase psychological well-being by focusing people’s energy around a particular behavior, and, as a result, they are more likely to follow through on the action.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Consider: In a series of experiments, marketing and behavioral psychologists Melanie Rudd, Jennifer Aaker, and Michael Norton asked participants to perform either concrete actions (like “increase the amount of materials or resources that are recycled” and “give those who need a bone marrow transplants a better chance at finding a donor”) or abstract actions (like “support environmental sustainability” and “give those who need bone marrow transplants greater hope”). For each experiment, participants had a certain amount of time to complete the task. They also completed a survey assessing their own happiness and their ability to make others happy, as well as their beliefs about the impact of the actions they took and whether they thought they achieved the provided goal. The researchers found that the participants who performed the concrete actions were more likely to feel successful at achieving the task and felt happier with their actions. The researchers suggest that more-specific actions leave people happier, because it closes the gap between their expectations and the reality of what they can do. They theorize that framing actions using concrete language can overcome what they refer to as “helper burnout”—when the inability to achieve a goal leads to frustration, disappointment, and disengagement. Framing actions in concrete terms increases positive feelings toward one’s accomplishments and, as a result, can lead to sustained engagement and action.

2. Make It Feel Achievable

Efficacy is fundamental to strong calls to action. People need to believe their participation will make a difference, and that they have the power and ability to take that action. As psychologist Albert Bandura writes:

Unless people believe they can produce desired effects by their actions, they have little incentive to undertake activities or to persevere in the face of difficulties. Whatever other factors may serve as guides and motivators, they are rooted in the core belief that one can make a difference by one's actions.

Define American’s #wordsmatter campaign video explains that only actions, not people, can be illegal according to a Supreme Court ruling, and that many undocumented immigrants come to the United States legally. The campaign targeted media representatives and asks them to make a pledge to use accurate language.

Define American’s #wordsmatter campaign video explains that only actions, not people, can be illegal according to a Supreme Court ruling, and that many undocumented immigrants come to the United States legally. The campaign targeted media representatives and asks them to make a pledge to use accurate language.

Researchers have found, for example, that people are less likely to help others when the number of those in need is high, because they feel their effort is only “a drop in the bucket” in solving an overwhelming problem. This state is called “pseudo-inefficacy.” The positive feelings from helping a few do not outweigh the negative feelings of not being able to help everyone. As a result, people are less likely to act.

We see the power of a strong call to action in the work of Define American, a nonprofit organization dedicated to changing how media covers immigration in the United States. As part of its efforts to move away from harmful narratives that dehumanize immigrants and present them as a homogenous group, the organization launched its #wordsmatter campaign, which asks news organizations to commit to not using the term “illegal immigrant.” The goal: Change how news organizations talk about the issue by focusing on the words they use to describe the people in their stories. The call to action: Use the term “undocumented” instead of “illegal” when covering news related to immigration. This specific call to action ladders up to the bigger goal of shifting the narrative on immigration and focuses on a behavior that feels doable for journalists. So far, ABC, NBC, the Associated Press, CNN, and other national media companies have committed to not using the term. The Associated Press has also dropped the term “illegal immigrant” from its stylebook.

3. Make It Easy

Research tells us that people actively avoid information that obligates them to do something they don't want to do. To overcome this challenge, calls to action should not feel like an obligation or burden; they should ask people to do something they want to do and that they can do easily.

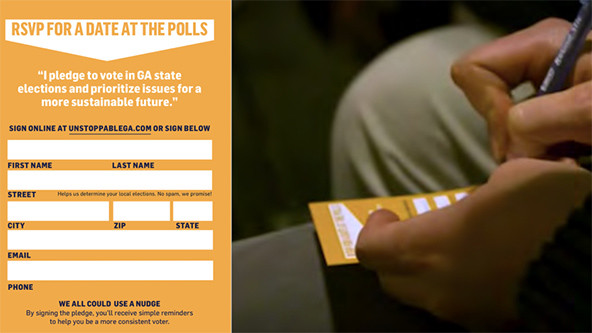

The vote pledge card Exposure Lab provided during its Big Screen Bloc Party sought to increase environmental turnout in Atlanta, Georgia.

The vote pledge card Exposure Lab provided during its Big Screen Bloc Party sought to increase environmental turnout in Atlanta, Georgia.

Consider the nonprofit Danish Nudging Network’s test of different approaches to reduce littering in public places. In Copenhagen, 90 percent of the population support recycling, yet one-third litter regularly. An experiment tested whether making it easy to throw away trash could change this habit by painting big green footprints on the ground that lead people to trashcans. The study found that the footprints reduced littering by 46 percent. In another example, public health studies on how to engage low-income Minneapolis parents in actions that protect their children from lead exposure found that parents were more likely to engage when presented with easy-to-do actions they could incorporate into their regular routines. For housing with older plumbing, for example, the more time water sits in service lines, the more lead will likely be in the water. Letting the water run for a short period of time before using it to cook or clean is one way to reduce the amount of lead in it.

Using “nudges”— small, positive reinforcements and directives that incrementally move behavior in a particular direction—also makes taking action easier. Nudges can include things like defaults, where people are automatically enrolled in programs that will help them (such as retirement savings or health coverage) unless they choose to opt out, and reminders (such as follow-up emails, calendar invitations, and text messages that help people follow through).

One field experiment, for example, found that a text message nudge following a film about corruption significantly increased corruption reporting within communities in Nigeria. And Exposure Labs used reminder nudges as part of its Big Screen Bloc Party film series to drive voter turnout with passive environmentalists in Atlanta—people who care deeply about the environment but rarely show up at the polls. It placed pledge cards under guests’ seats asking them to commit to voting—to take a simple, immediate action. From there, it worked with the Environmental Voter Project on a series of follow-up texts and email messages to remind people of their pledge and provide upcoming election dates. Pairing the pledge with the storytelling power of film resulted in higher-than-average pledge rates at events, and the majority of pledge-takers turned up at the polls.

4. Make It Feel Like Everyone Else Is Doing It

We are social creatures with an innate need to belong within social groups. When we perceive a behavior as a group norm, it motivates us to engage in that action because we assume everyone else is. People are also motivated to maintain a positive sense of self. As a result, we often seek and justify actions that are in our self-interest and help us maintain status within our social groups. Identifying a community based on a shared group identity and connecting your action to that identity will help them see their personal interest in engaging in the behavior.

For example, one study released by the USC Norman Lear Center Media Project found that people were more likely to click a “donate” button on a story about homelessness when the action was framed as a moral and social norm (“To do some good, join the 33,354 people who have used Action Button, and click an amount below to make a donation today”) as compared to a general call to action (“Click an amount below to make a donation today”). Similarly, social psychologists Gregg Sparkman and Greg Walton conducted an experiment in which people in line at a cafe read either a statement describing how some people have limited their meat consumption (existing norm) or a message describing how some people are starting to limit their meat consumption (new norm). People who read the message about the new norm were 34 percent more likely to order a meatless meal, as compared to the 17 percent of those who read the existing norm.

Another example is the inspiring Immortal Fan campaign developed by Ogivly & Mather. With the goal of increasing organ donations in Brazil, the campaign connected becoming an organ donor with the robust sense of pride among football fans in Brazil. It used stories featuring real patients on waiting lists to inspire donors and framed the call to action as “becoming immortal fans.” It also made it easy to sign up for an organ donation card across multiple online and offline platforms. In the end, the campaign drew in more than 51,000 new donor cards, and the waitlist for heart and corneal transplants reduced to zero.

The Immortal Fan campaign, produced by Ogivly & Mather, increased organ donations by attaching the action of becoming an organ donor to the identity of sport fans.

Storytelling-driven efforts can inspire people to engage in social change, but mobilizing action requires that organizations thoughtfully design what they ask people to do, and how. Nonprofits must anchor their approach in the science of how people think and behave, and translate change goals into calls to action that are specific, feel achievable, make taking action easy, and align with group norms.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Max Steinman, Annie Neimand, Samantha Wright & Ann Christiano.