Abriendo Oportunidades mentors provide training to indigenous Guatemalan girls. (Photo by Phil Borges/Population Council)

Abriendo Oportunidades mentors provide training to indigenous Guatemalan girls. (Photo by Phil Borges/Population Council)

The majority of adolescent girls—girls aged 10 to 19—live in low- and middle-income countries, and are well poised to build the capabilities they need to fulfill their potential, and to contribute to the health and well-being of their families and communities. Empowering them represents an unprecedented opportunity for progress: When we keep adolescent girls healthy, safe, and in school, and give them skills and a say in their own lives, they have a path to healthy, productive adulthood. They are better able to gain knowledge, are less likely to become pregnant, and have more earning power. Society as a whole also benefits: Greater opportunity for young women to join the workforce can help close the workforce gender gap and boost national gross domestic products.

Based on evidence showing that investing in girls yields substantial returns, including reductions in early pregnancy and increased earning power, more and more donors, policymakers, and nonprofits are focusing on girls. Since 2015, the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), for example, has invested more than $750 million in HIV prevention for girls and young women in 15 countries through the DREAMS Initiative. And at the 2017 Family Planning 2020 Summit, most of the 42 countries that committed to empowering women and girls with family planning made adolescents a focus of their plans.

Some combine cash transfers with girls’ clubs, or school-based sexual education with youth-friendly health services, to pursue the same goals. But these efforts aren’t necessarily evidence-based, nor are they standardized to reflect what works.

However, many organizations that deliver services to adolescent girls lack systematic guidance for programming. In particular, while many recognize the multi-faceted nature of the risks that girls face, few agree on the most effective ways to implement intersectoral approaches that address them. Some combine cash transfers with girls’ clubs, or school-based sexual education with youth-friendly health services, to pursue the same goals. But these efforts aren’t necessarily evidence-based, nor are they standardized to reflect what works. Policymakers and nonprofits need a practical, multi-sectoral framework to prioritize approaches to empowering girls and maximize the impact of their investments.

A New Framework for Empowerment

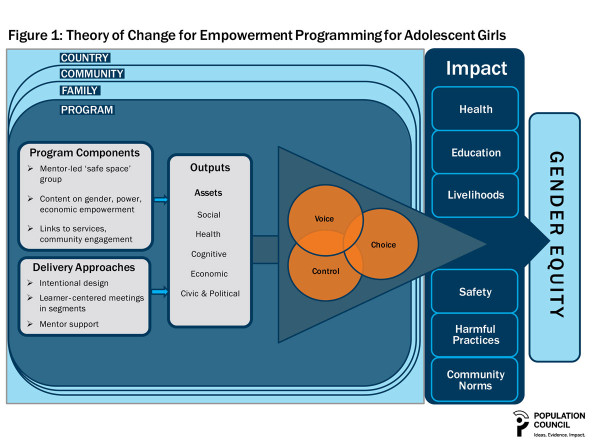

Based on our experience at the Population Council, which conducts research and develops solutions to health and development issues, and the evolving body of evidence on what works to improve girls’ lives, we developed a theory of change for empowerment programming for adolescent girls. This theory of change provides a practical framework for designing and implementing programs that center around girls’ diverse needs (such as saving money and preventing unintended pregnancy) and address multiple determinants of risk (such as social isolation or school drop-out). In doing so, these programs empower girls to make decisions and positively affect outcomes of importance to themselves, their families, and their communities. With its emphasis on inclusive intersectoral approaches, the framework also has relevance for adolescent boys and other demographics who may be disempowered because of social status, ethnicity, or disability.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

The framework contains seven core programmatic components and four delivery approaches that can help programs reach the right girls with the right content at the right time. It recognizes that girls cannot create transformational social change on their own. Indeed, factors such as gender-equitable policies, poverty reduction, education reforms, and other systemic changes influence girls’ transitions to adulthood, and can enable, amplify, or hinder the effects of empowerment programming. The framework takes account of this by reflecting a socio-ecological perspective, situating girl-centered programs within families, communities, and countries.

Programs that aim to empower adolescent girls should incorporate key components and delivery approaches to build assets that drive gender equity.

Seven Components of Community-Based Empowerment Programming

1. Girls’ groups. Programs should bring peers and mentors together in girl-only groups stratified by age, schooling, and/or marital status to build supportive relationships. For benefits beyond social capital, programs also need to build girls’ knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy, and link them to essential services and social institutions.

2. Safe Space. Girls’ group meetings should take place in existing venues, such as community centers or classrooms after hours, that are private and safe so that girls feel comfortable participating and communicating about sensitive topics.

3. Mentors. Ideally, mentors are young women from the local community who have navigated challenges like the ones program participants are experiencing. Mentor roles should include delivering core content, serving as role models, and providing practical assistance in emergencies.

4. Content on gender and power. Most girls’ empowerment programs include life-skills training centered on sexual and reproductive health; to be most effective, content must explicitly address gender norms and power dynamics in sexual relationships.

5. Economic empowerment. Programs also need to address the influence of economic factors on girls’ participation and impact. Economically empowering girls directly (such as through cash transfers) or indirectly (such as through financial literacy training) can reduce parental opposition and counteract the opportunity cost of participation.

6. Referral networks. Mentors should also be part of an active referral network, referring girls to outside services and resources like clinics and banks as needed. Programs can also help by providing an escort or helping defray transport or service costs.

7. Community engagement: Program staff, parents, and community members should come together to build knowledge and shift attitudes, thus contributing to an enabling environment where gender norms don’t inhibit girls’ participation or limit program impact. For instance, facilitated conversations can foster discussion between parents and other influential community members on themes related to girls’ group activities.

Four Program Delivery Approaches

Empowerment programs need to include not only the right elements—the “what” as described above—but also the right approach to implementation—the “how.” The way an organization implements the seven components can make or break a program.

1. Intentional design and targeting. Community-based programs can help reach marginalized adolescents, such as girls who are married, out-of-school, or living with disabilities. Many of these girls miss out on programming delivered through common channels like clinics and schools, yet face the highest risk. Organizations must gather detailed local information about adolescents’ diverse circumstances to determine where, and with whom, they should work. In Ethiopia, the Population Council used a community-level, child well-being assessment tool called the Child Census to identify areas with the most out-of-school and/or married girls. It then used the results to inform decisions about which kebeles (public administrations) were likely to benefit most from the expansion of Berhane Hewan (Light for Eve), a child-marriage prevention program.

2. Frequent meetings in segments. Another strong delivery approach is to set up meetings between groups of girls who share distinct characteristics, such as age or marital status, at least once a week for a year or longer. Girls who participate regularly have more program exposure and derive more benefits. In urban Ethiopia, for example, Biruh Tesfa (Bright Future) aims to reduce the social isolation of extremely disadvantaged, out-of-school girls. Trained mentors go house to house, inviting excluded segments of eligible girls—including domestic workers, girls living with disabilities, and rural-to-urban migrants—to regular meetings in safe locations donated by local kebeles. Girls meet as often as five times per week at times that vary to accommodate their work schedules.

3. Learner-centered, interactive pedagogy. Training approaches should be interactive, participatory, and learner-centered. Mentors can emphasize skill-based learning and critical thinking using materials adapted for individual girl segments. In Bangladesh, Bangladeshi Association for Life Skills, Income, and Knowledge for Adolescents (BALIKA) aimed to delay marriage among girls aged 12 to 18 in areas with the highest child marriage rates. It used three skills-building approaches to empower girls: 1) educational support; 2) training on life skills and gender rights with the It’s All One Curriculum to deliver unified education on sexuality, gender, HIV, and human rights; and 3) training on skills for modern livelihoods.

4. Continuous support for mentors: Program success depends on mentor performance. Adequate training, supportive supervision, and opportunities for mentors to interact all enhance mentor effectiveness and retention. It’s important that programs offer them compensation similar to comparable local jobs. In rural Guatemala, Abriendo Oportunidades (Opening Opportunities) works with rural indigenous girls to reduce their disadvantage and improve their lives. Girls meet weekly with female mentors aged 18 to 25 who run and facilitate the program. These mentors enable culturally sensitive discussions of issues and become positive role models. Mentors also participate in quarterly “training spaces” to learn new content, improve their skills, and learn from each other. Site coordinators provide weekly mentor support, monitor their performance, and provide constructive feedback.

What Delivery Looks Like in Practice

The overall design of Biruh Tesfa, described above, illustrates the combined potential of these four delivery approaches. Working through local female mentors, the program uses interactive techniques to build basic literacy skills, as well as to provide information and services to reduce sexual exploitation, abuse, and HIV risk. Mentors also provide girls with vouchers and referrals for free health and HIV services, often accompanying girls who are scared to go alone. Between 2006 and 2016, more than 75,000 out-of-school girls in the poorest areas of 18 cities participated in the program. An evaluation found positive effects that included strong social support, HIV knowledge, and desire for HIV testing, as well as literacy and numeracy for girls who had never had formal schooling.

We define assets as the store of value—the human stock—that girls can use to reduce risk and expand opportunity. For example, self-esteem can help them excel in school or at a job interview, while financial assets can protect them from risky sexual relationships.

BALIKA uses a similar delivery model. Girls meet weekly with mentors in safe, girl-only locations called BALIKA Centers, typically located in schools, to develop friendships, learn new technologies, borrow books, and acquire life skills. In the initial phase—which is currently expanding—more 9,000 girls in 72 communities participated over 18 months. Teachers and mentors recruited girls, liaised with families and communities, ran center activities, and engaged with community support groups. A randomized controlled trial evaluation found that BALIKA reduced the likelihood of child marriage by up to one-third, laying the foundation for better health, educational, economic, and social outcomes. These results show that it is possible to reduce the prevalence of child marriage in a relatively short time, which BALIKA did by working with communities to implement holistic, skills-building programs for girls that elevated their status.

Building Girls’ Protective Assets

Programs that deliver all seven components using the delivery approaches above work to build girls’ protective assets. We define assets as the store of value—the human stock—that girls can use to reduce risk and expand opportunity. For example, self-esteem can help them excel in school or at a job interview, while financial assets can protect them from risky sexual relationships. Rather than approaching girls through a single sector, an asset-building approach considers the whole girl.

Protective assets include social assets like trusted relationships with peers and adults, and health and human assets such as access to health services. Examples of cognitive assets include literacy, problem solving, and critical consciousness. Economic assets include financial literacy and budgeting skills, while things like leadership skills, negotiation skills, and identity cards are civic and political assets.

The thinking is that when girls gain assets, they are empowered as individuals and as groups, which they express by exercising voice, choice, and control. Girls use their voice—their say in decision-making in households, politics, business, and other realms—through participation, leadership, and collective action. Choice means they have the option to stay in school or join the labor force, and can decide whether, when, and with whom to have sex or to marry. And control means they have power over their bodies and mobility, income, and other resources. It also means having equitable legal rights and access to justice, as well as freedom from discriminatory social norms.

As girls exercise voice, choice, or control, they may start to disrupt social norms. Within supportive families, communities, and policy environments, this can improve girls’ health, education, and livelihoods. And if many girls in a given community participate in empowerment programs, this may create a “tipping point” that fosters new norms about girls’ value that endure. Ultimately, these shifts will substantially improve girls’ well-being and life chances, and promote gender equity.

We need intersectional approaches to reduce the wide-ranging risks that millions of adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries face. We hope that this practical, multisectoral framework will help donors, governments, and nonprofits empower girls, harness the potential of the largest-ever generation of adolescents, and promote gender equity.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Miriam Temin, Sajeda Amin, Thoai D. Ngo & Stephanie Psaki.