Entrepreneurship. It’s the creative juice that fuels the economy. It is also one of the most effective tools we have to chip away at the growing wealth gap. Business ownership has long provided a path to economic mobility and wealth creation, at least for those with the resources to get started. Yet many valid new ventures die or languish for lack of capital. That’s especially true for ventures led by women, people of color, rural entrepreneurs, and for social enterprises with unconventional models.

We’ve all seen the stats: Two-thirds of venture funding in the United States goes to just three states, and most of it to ventures led by white males. Women and minorities are also at a disadvantage when seeking angel investment and bank loans. When we leave out large swaths of the population, we all suffer.

Part of the explanation for this gap lies with human nature: We tend to favor people who are similar to us—what researchers call homophily—and when the decision makers are white men of a similar socio-economic background, the results are all too predictable.

What if instead of fighting the forces of unconscious bias, we could harness them? What happens when we remove the traditional financial gatekeepers and open up investment decisions to the community? If we change who does the funding, does that change who gets funded?

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

A great experiment in democratized finance is underway, and it is beginning to shed light on these questions. Recent changes in federal and state laws have given all Americans the ability to invest in small businesses and ventures they believe in. Until now, that natural impulse to invest locally or according to personal values was very hard for all but the wealthiest people to act on.

The last piece of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act went into effect just over a year ago and is already transforming the funding landscape, allowing entrepreneurs to bypass traditional gatekeepers and reach out directly to their, customers, supporters, and the public at large for investment capital.

This kind of community-based investing allows more niches, remote areas, and smaller projects than the economics of professional underwriting allow. And what the community, as underwriters, lack in professionalism, they make up for in local intelligence, empathy, capacity, and bandwidth.

The Community Capital 500

At investibule, a Public Benefit Corp I cofounded with Arno Hesse, we’ve had a unique view of this grassroots financial revolution. For the past year, we have aggregated crowdfunded offerings open to all investors—what we call “community capital.”

We take a broad and inclusive view of community capital, spanning regulations, funding types, and platforms. That includes equity, debt, and revenue share offerings conducted under the federal JOBS Act, intrastate laws (where possible), and direct public offerings. It also includes some non-securities, such as no-interest loans, rewards, and “pre-pay” opportunities.

To be clear, we do not handle transactions, but aggregate offerings across 30-plus funding platforms. The goal is to make it easy for individuals, regardless of their net worth, to discover opportunities to invest in and support businesses they believe in.

To provide a glimpse into the future of funding, we recently analyzed the first 500 offerings featured on the site, from September 2016 through mid-August 2017. Let’s call them the Community Capital 500 (CC500). Here is what we learned.

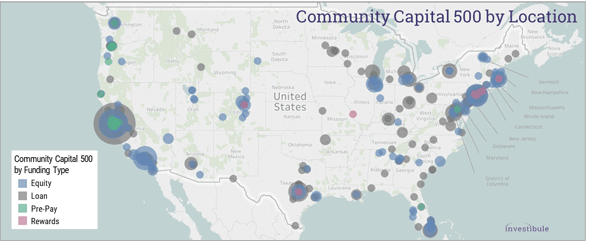

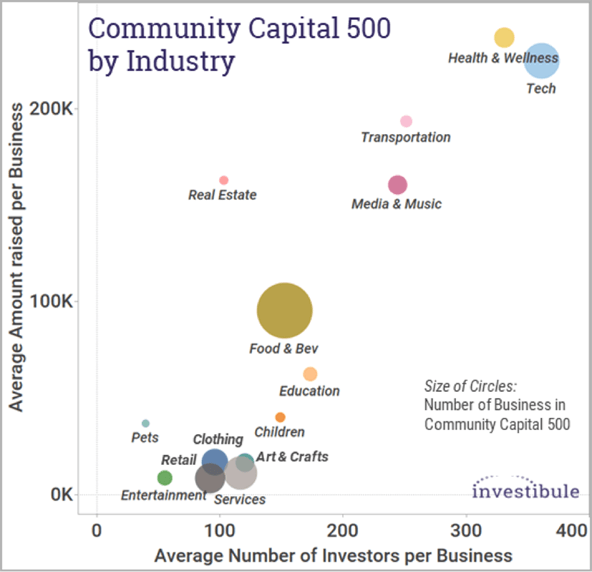

Business and Geographic Diversity

The CC500 is comprised of a vibrant mix of businesses. While tech reigns in the venture capital world, it is a distant second to food and beverage ventures, in terms of volume, among those we analyzed. Retail, health and wellness, clothing, entertainment, transportation, media and music, education, and service-oriented businesses are all part of the mix.

Together, these 500 ventures offer a snapshot of American ingenuity. They are involved in industries as wide ranging as grassfed beef, the newly legalized kind of grass, and even jetpacks. There are family-run businesses, women and minority-led ventures, co-ops, and B Corps.

As in conventional finance, a handful of coastal cities represent a large share of the acitvity. But funding is spilling over into other areas, including Alabama, Wyoming, and the shores of Hawaii.

Small Checks, Big Impact

People are investing in these businesses. Sixty-eight percent of the CC500 successfully raised their minimum funding goal or more as of mid-August, and another 12 percent still had time to go—a far better success rate than most busineses see when seeking angel or venture funding, or even a bank loan.

All told, the CC500 raised more than $52 million from more than 72,000 investors—an average of $161,000 and 234 investors per funding campaign. Offerings ranged from small loans on Kiva, which crowdfunds zero-interest loans of up to $10,000, to $1 million-plus equity crowdfunding offerings.

It’s clear community capital is financing small businesses and ventures that otherwise might fall through the cracks of conventional finance, via small checks from lots of investors.

Social Justice

The data is especially promising for women and people of color. In fact, community capital is flipping traditional venture capital funding bias on its head. While still underrepresented as a whole, women and minority-owned businesses in the CC500 outperformed the average: Seventy-six percent of women-owned ventures and 73 percent of minority-owned ventures sucessfully raised funding, compared to 68 percent for the CC500 as a whole.

Community capital is helping entrepreneurs like Lynn Johnson and Allison Kenny of Spotlight Girls expand their Oakland, Calif.-based empowerment programs for girls nationwide. It’s helping Native American Natural Foods restore buffalo to the Great Plains and an economic livelihood to the Lakota people of South Dakota. It’s also helping Century Partners extend the Detroit revival to overlooked neighborhoods and encouraging their residents to participate.

Spotlight Girls cofounders Lynn Johnson and Allison Kenny with their daughter. (Photo courtesy of Spotlight Girls)

Spotlight Girls cofounders Lynn Johnson and Allison Kenny with their daughter. (Photo courtesy of Spotlight Girls)

Community capital is tilting toward social justice and toward building a financial system that serves all people, not just those with the right connections and collateral. By allowing community members to share in their success (or failure, as may be the case), this new form of funding can help empower communities, build wealth, and keep profits local.

A Global Phenomenon

The investibule data adds to the growing body of evidence that crowdfunding is fulfilling its promise of getting capital to a wide range of deserving entrepreneurs, no matter their zip code or skin color, or where they went to school.

The most sweeping study to date comes from PriceWaterhouseCoopers and the Crowdfunding Centre. Their Women Unbound study analyzed 465,000 rewards-based crowdfunding campaigns from nine of the largest crowdfunding platforms globally, including Kickstarter and Indiegogo. The campaigns sought seed funding to develop or launch new products or businesses. These campaigns are outside the realm of investment, but the dynamics that motivate backers and investors are similar.

The study found that, overall, female-led campaigns were 32 percent more successful at reaching their funding targets than male-led campaigns. In the United States, women were successful 24 percent of the time compared to 20 percent for their male peers. Although they set on average lower funding targets, women campaigners attracted higher pledge amounts from individual backers—$87 per backer on average, compared to $83 for men.

Evolving the Model

While it’s not yet clear to what degree individual investors and communities are benefiting, early anecdotal evidence suggests that some of these ventures are creating jobs and sharing profits with investors.

Meanwhile, other challenges remain. How do we raise awareness and educate investors and entrepreneurs about responsibly using these new funding tools? How do we get community capital to underserved communities that can benefit but have limited resources to invest? Do we need new models?

As we ponder these questions, foundations, impact investors, local governments and other stakeholders might consider what role they could play. For example, could they lend social validation or financial support to funding campaigns within their target communities? There are already examples of this kind of collaboration.

In New York City, the Department of Small Business Services has launched a partnership with the microlender Kiva aimed at supporting women entrepreneurs. The city will provide the first 10 percent of loans sought by New York-based women on Kiva, with a goal of supporting at least 500 businesses over three years. And the Michigan Economic Development Corp. has contributed more than $4 million to date in matching grants of up to $50,000 each to community projects that have successfully met their public fundraising targets on a local rewards-based crowdfunding portal called Patronicity.

This emerging grassroots funding model presents an opportunity for foundations and other impact players to engage with the populations they seek to help, and experiment with a more “bottom-up” model. They may find that they benefit from the wisdom of these communities.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Amy Cortese.