Illustration by Justin Renteria

Illustration by Justin Renteria

Recent news coverage of Hot Bread Kitchen reads as if it were written about two different organizations. The New York City bakery is widely acclaimed for its innovative selection of international breads, but it is simultaneously an award-winning workforce development program. Hot Bread Kitchen is a hybrid organization: Its employees, mostly low-income immigrant women, bake bread inspired by their countries of origin, while learning job skills that can lead them to management positions in the food industry. In this way, Hot Bread Kitchen combines two traditionally separate models: a social welfare model that guides its workforce development mission and a revenue generation model that guides its commercial activities.

To outside observers, combining social welfare and revenue generation models might seem unnatural. But Hot Bread Kitchen’s founder, Jessamyn Rodriguez, whose professional experience includes training at Daniel Boulud’s flagship restaurant as well as a decade working in international development, pursued a vision for how each would complement the other. The business model would use product sales to fund its social mission, reducing dependence on donations, grants, and subsidies, as well as to scale up the organization. Rather than take a nonprofit model and add a commercial revenue stream—or take a for-profit model and add a charity or service program—Hot Bread Kitchen’s integrated hybrid model produces both social value and commercial revenue through a single, unified strategy.

Hot Bread Kitchen exemplifies a larger trend among social innovators toward creating hybrid organizations that primarily pursue a social mission but rely significantly on commercial revenue to sustain operations. Such hybrids have long existed in certain sectors, such as job training, health care, and microcredit—but in recent years they have begun to appear in new sectors, including environmental services, consulting, retail, consumer products, catering, and information technology.

As part of the first large-scale, quantitative research study of nascent social entrepreneurs,1 a collaborative team from Harvard Business School and Echoing Green, a nonprofit with a 25-year record of supporting early stage social entrepreneurs, reviewed more than 3,500 recent Echoing Green Fellowship applications2 to better understand hybrid models. Over the last five years, applications from organizations that combined earned and donated revenue grew significantly: In 2010 and 2011, almost 50 percent relied on hybrid models vs. 37 percent in 2006. These entrepreneurs sought to address social issues in domains as diverse as hunger, health care, economic development, environment, education, housing, culture, law, and politics. This recent increase in the number of hybrids results in part from social entrepreneurs’ willingness to be less dependent on donations and subsidies, as well as from an increased interest in creating sustainable financial models in the wake of the 2007-08 financial crisis.

Like hybrid species in nature, hybrid organizational models can be a fountain of innovation. But they also face distinct challenges that may prevent them from thriving. When organizations combine social mission with commercial activities, they create unfamiliar combinations of activities for which a supportive ecosystem may not yet exist. Hybrids also must strike a delicate balance between social and economic objectives, to avoid “mission drift”—in this case, a focus on profits to the detriment of the social good.

This article examines hybrids and the specific challenges they face in legal recognition, financing, pricing of goods and services, and creating a balanced organizational culture. We also explore emerging solutions to these challenges for those seeking to combine the value-creating potential of for-profits and nonprofits.

Integration as the Hybrid Ideal

The organization of the commercial and social sectors has long been governed by an assumption of independence between commercial revenue and social value creation. For more than a century, activities necessary to create commercial revenue, it was assumed, could not substantially affect or improve on social welfare, and vice versa. Thus most organizations that sought to pursue social value and commercial revenue simultaneously pursued differentiated strategies.

For instance, corporate philanthropy programs were viewed as a nonbusiness activity and were conducted at arm’s length from corporations’ core activities. On the other hand, many nonprofit organizations attempted to sell products or services, creating revenue streams to reduce dependence on philanthropic and public funders. Yet earned income programs, often unrelated to the core activities of nonprofits, did not always live up to expectations.3

Today it is clear that the independence of social value and commercial revenue creation is a myth. In reality, the vectors of social value and commercial revenue creation can reinforce and undermine each other. The social consequences of the recent financial crisis demonstrated with great clarity the danger of “negative externalities”—social costs resulting from corporate profit-seeking activities. But in some cases, “positive externalities” may also exist. It is this possibility that integrated hybrid models seek to exploit.

When we talk to entrepreneurs and students about hybrid organizations, a common theme that emerges is what we call the “hybrid ideal.” This hypothetical organization is fully integrated—everything it does produces both social value and commercial revenue.4 This vision has at least two powerful features. In the hybrid ideal, managers do not face a choice between mission and profit, because these aims are integrated in the same strategy. More important, the integration of social and commercial value creation enables a virtuous cycle of profit and reinvestment in the social mission that builds large-scale solutions to social problems.

Perhaps the most visible example of the pursuit of the hybrid ideal is microfinance. For many, the revolutionary appeal of the microfinance movement was that poverty might be alleviated in a way that does not require continuous subsidies. When carefully managed, an additional loan can equal both more revenue and more of the desired social impact. As we have seen in microfinance and other industries where hybrids have grown, however, the real-world pursuit of the hybrid ideal is fraught with potential missteps. Recent scandals and critiques of microfinance institutions have focused on a drift away from social mission to more typical for-profit priorities—leading many observers to question whether social problems, such as extreme poverty, can be solved through strategies that also produce revenue.

Despite these obstacles, our research reveals that some hybrids manage to integrate social and commercial activities sustainably. Still, even when leaders manage to avoid mission drift, integrated hybrids can struggle to find a suitable place between the for-profit and nonprofit sectors, especially in their quest for legal recognition and access to capital, markets, and labor. We review these challenges in the four sections below.

Challenge #1: Legal Structure

Until recently, organizations in most countries had two main legal structure options, each offering certain benefits. For-profits focus for the most part on shareholder value maximization and are permitted to distribute returns to investors. Nonprofits singularly pursue a charitable purpose, and in return, governments offer substantial tax benefits. Nonprofits also benefit from social legitimacy and goodwill that attracts grants, donations, volunteers, pro bono professionals, and other free or inexpensive resources.

In this context, an entrepreneur seeking to create a hybrid organization faces a difficult and often confusing dilemma. If the organization becomes a nonprofit, selling products or services, it may have to pay tax on revenues associated with those activities and it could also lose its tax-exempt status if the activities are sufficiently disconnected from its primary charitable purpose. Yet, if the organization becomes a for-profit, it may be discouraged from pursuing social impact by the pressures of competitive markets as well as fiduciary responsibilities that generally prioritize profit maximization over other concerns. In other words, hybrid entrepreneurs can claim the organizational benefits of only one of the multiple forms of value they create.

Indeed, a hybrid that registers as a nonprofit cannot access equity capital markets because it cannot legally sell ownership stakes to investors. But if a hybrid incorporates as a for-profit, it cannot offer the same tax benefits to donors as registered nonprofits can, even if these approaches lead to the most effective social solution. Further complicating the choice is the reality that entrepreneurs cannot fully anticipate their future resource needs at the time legal registration choices are made, and thus risk being prematurely locked in to one sector or the other.

One solution adopted by a number of hybrid entrepreneurs is to exploit the benefits of both legal structures. This typically entails the creation of two separate legal entities, one a for-profit and the other a nonprofit. Embrace, an organization attempting to commercialize a low-cost incubator for premature infants, was originally a nonprofit social enterprise. After testing the product in India, the organization explored various options for financing further growth—but found the financing alternatives under the 501(c)(3) umbrella to be limited. To access a wider pool of capital and scale up its operations, Embrace created a for-profit called Embrace Innovations. The nonprofit owns equity in the for-profit, a structure that gives the nonprofit power to control the activities of the joint venture while protecting its social mission.

Despite its benefits, this multiple-entity approach also entails complex design requirements and administrative separation that can burden management. To create better options for hybrids, several efforts are under way to establish new types of legal structures. In the United States, there are three such forms: the L3C (Low-Profit Limited Liability Company), the Benefit Corporation, and the Flexible Purpose Corporation. The L3C is a variant of an LLC, designed primarily to enable companies to access investment from tax-exempt sources such as private foundations. The Benefit Corporation is a corporate form passed in seven states and pending in four others that requires organizations to consider a designated social purpose and corresponding social impact alongside financial analysis in making strategic and tactical business decisions. The Flexible Purpose Corporation, which has passed in California and Washington (where it is called the Social Purpose Corporation), requires boards and management to agree on one or more social and environmental purposes with shareholders, while providing additional protection against liability for directors and management.

Around the world, other hybrid legal structures have emerged. In the UK, for example, a Community Interest Company (CIC) provides tax benefits to hybrids that agree to limit their distributions to investors. A CIC, once given governmental approval, has its assets “frozen” and designated for general community benefit. Investors can receive capped dividends on their investment, but the principal is never retrieved. Yet in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere, legal registration is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of how legal systems affect the growth and success of hybrids. Areas of corporate law, such as the tax code, were not built for organizations that pursue social and financial value. Still, the emergence of new hybrid legal structures will likely encourage increased hybrid activity. What remains to be seen is which legal structures will be the best fit for hybrids.

Challenge #2: Financing

As in the case of legal structures, financing has evolved for for-profits and nonprofits, but not for hybrids. On the one hand, the for-profit sector has sophisticated vehicles for financing through equity and debt. On the other hand, a smaller but similarly specialized infrastructure of national and community foundations, early stage fellowship grantors, and venture philanthropists exists to provide funding to the nonprofit sector. Although these sources of nonprofit capital are scarce, they have long been the typical source of funding for organizations pursuing a social mission.

The current pathway to funding for hybrids is not so clear. One approach is to adopt a differentiated funding strategy that accesses profit-seeking investors for commercial activities and nonprofit fundraising and public subsidies for social activities. Sanergy Inc., a waste conversion startup that installs toilets in some of the poorest slums in the world, leverages such an approach. During 2011, Sanergy’s leaders created two organizations: a nonprofit and a for-profit, each of which is uniquely dependent on the other for its sustained existence. Under this hybrid structure, the for-profit develops and scales up capitalintensive sanitation technology and infrastructure, and the nonprofit supports sanitation infrastructure and services within low-income communities. Reflecting on this funding approach, David Auerbach, Sanergy’s co-founder, said: “We’ve found that grant funders are comfortable with the social mission priorities in the nonprofit, and that investors like the fact that we cannot fulfill our financial goal without actually providing hygienic sanitation. Both are inextricably linked.”

Instead of relying on a differentiated funding strategy, many hybrid entrepreneurs focus initially on getting funding from the nonprofit sector. Apart from traditional nonprofit sources of funding in the form of grants or donations, program-related investments (PRIs)—which enable private foundations to allocate investments through equity, debt, or a mixture of both—have increased access to capital for US hybrids. We find that many hybrid entrepreneurs have been able to find supportive capital partners through this type of early stage financing.

Meanwhile, some hybrid entrepreneurs have started targeting more typical for-profit sources of funding. In the case of Frogtek—a for-profit social venture that develops business tools for microentrepreneurs in emerging markets—CEO David del Ser decided to incorporate as a for-profit because he believed startup financing could come from mainstream venture capital, enabling faster growth. But del Ser admits that attracting venture capital has been significantly more challenging than initially envisaged. He attributes the difficulty to investors’ inability to quantify Frogtek’s risk even though the return potential is attractive. Still, Frogtek has been successful in engaging angel investors whose values align with those of the organization.

Clearly, traditional early stage equity financing methods used by the venture capital industry are not suited to social ventures. Rather, investors who embrace the same dual objectives as hybrid entrepreneurs are needed. One such group is impact investors who are comfortable with hybrid models and their blend of social value creation and commercial revenue. Despite recent estimates that the global impact investing market will be at least $500 billion within the next decade,5 most hybrid entrepreneurs we have encountered still experience difficulty in raising capital. Solving this challenge will require changes in the mindsets of investors, who will have to accept a return that can range from a below market to market rate, as well as improved capital placement structures.

Challenge #3: Customers and Beneficiaries

Traditional businesses usually think of their consumers as customers, whereas traditional nonprofits think of their consumer base as beneficiaries. Hybrids, however, break this traditional customer-beneficiary dichotomy by providing products and services that, when consumed, produce social value. When consumption yields both revenue and social value, customers and beneficiaries may become indistinguishable. This kind of integration is powerful, in part because it resolves the deeply felt tension between mission and growth. When customers and beneficiaries are the same, focusing on growth doesn’t take away resources from beneficiaries; rather, growth of sales and fulfillment of mission are inseparable. It should be no surprise that many of the fastest growing hybrids have this feature, including microfinance and other models in the developing world that produce goods and services for the bottom of the pyramid.

Depending on the social issue that they aim to address, however, hybrid entrepreneurs may not be able to integrate social value creation with earning commercial revenue in a single transaction. An obvious challenge to this type of integration is that many beneficiary groups lack the financial means to pay for the value they receive from a product or service. Even when products or services create financial value for beneficiaries, the realization of that value may be so distant that it is impractical to recapture. For example, educational programs might increase a child’s future earnings, but organizations cannot recoup the child’s future wealth. For this and a myriad of other areas addressed by the social sector, integration of customers and beneficiaries may never be possible or desirable.

Hybrid organizations addressing these types of social problems typically differentiate between customers and beneficiaries. Mobile School, a Belgian nonprofit, for example, provides educational materials to children who live on the streets through a “mobile school,” basically a box on wheels containing blackboards and educational board games. Because Mobile School serves poor children, it cannot sustain its operations through selling materials or equipment to its beneficiaries. Instead, founder Arnoud Raskin launched a consulting business, Streetwize, which is incorporated as a social purpose company in Belgium. Streetwize’s activities, which are separate from Mobile School, generate revenue to sustain the nonprofit’s operations. The board members of Mobile School are shareholders of Streetwize.

Although they can be effective and sustainable, such differentiated approaches raise a number of challenges for hybrids that may need to make trade-offs between serving customers and beneficiaries. As Raskin puts it, “When we created Streetwize, there was a risk for Streetwize and Mobile School to grow into two disconnected organizations. Although they are two separate entities, engaged in different activities, the challenge is to make sure that they both remain focused on the mission of Mobile School. I view my role as making sure that we never compromise on this.”

Yet such differentiated approaches are not the only options for hybrids. Some still have different populations of customers and beneficiaries, but their social and economic activities are more integrated. The beneficiaries of Hot Bread Kitchen, for example, produce and sell a product for customers, while learning job skills. In this case, social value is intimately related to sales, but is not contained in the product or service itself. Certain products and services that are valuable to both customers and beneficiaries create opportunities for even more integrated models. Indeed, for some hybrids such as commercial microfinance organizations, the beneficiaries of the service are the only customers of the organization. This overlap enables the organization to focus on one set of activities that fulfill its social and financial objectives. Like all hybrids, however, these organizations are still subject to the risk of mission drift, as they may give priority to profit seeking over social mission. This drifting may lead them to either start charging higher prices or expand their customer pool by targeting wealthier and more profitable market segments.

Challenge #4: Organizational Culture and Talent Development

All hybrid organizations face the challenge of remaining focused on their missions. At early stages, the passion and dedication of the entrepreneur can organically communicate such commitment within the organization. But as organizations grow, the influence of entrepreneurs on new staff becomes less direct and powerful. When direct influence weakens, culture becomes a critical means by which beliefs and values are communicated and maintained. Hybrids face the special challenge of building an organizational culture committed to both social mission and effective operations.

To keep the mission on course while still making enough money to sustain their operations, the leaders of hybrids must make deliberate cultural decisions. First, they must identify and communicate organizational values that strike a healthy balance between commitment to both social mission and effective operations. Equally important is the selection, development, and management of employees who are capable of recognizing and pursuing social and economic value.

Because hybrid organizations not widespread, job candidates with extensive experience or training in hybrid working environments typically do not exist. The alternative for hybrid entrepreneurs is to hire either people who have work experience in only one sector—be it the social or market sector—or a mix of people from both. Hiring people who all previously worked in the same sector decreases the likelihood of organizational conflict, but it significantly increases the risk of mission drift, as employees are likely to slip into the habits and skills they learned in their previous work. On the other hand, hiring a differentiated combination of people from disparate sectors can help the organization better balance its social and economic objectives but risks conflict between employees.

Bolivian microfinance NGO Banco Solidario (BancoSol) was one of the first to spin off its lending operations into a regulated commercial organization in 1992, transitioning from a typical nonprofit organization to a hybrid. As a nonprofit, BancoSol could not keep up with demand for loans from low-income entrepreneurs. The newly created hybrid organization would be in a better position to achieve this mission, as it would be financially self-sustaining. Needing both social work and banking skills, BancoSol hired a combination of employees from the social and business sectors and planned to train them to work together to achieve common goals. According to Francisco Otero, BancoSol’s first CEO, a balanced organizational culture would be created by “converting social workers into bankers and bankers into social workers.” Despite BancoSol’s training efforts, however, the single-purpose backgrounds of their employees made it hard for them to adjust to the hybrid model. Those with a social work background and those with a financial background ended up resenting each other and fighting constantly, so that the organization could hardly operate.

Another Bolivian commercial microfinance organization, Caja de Ahorro y Prestamo (Los Andes), launched three years after BancoSol. It learned from BancoSol’s experience and adopted a radically different hiring and socialization approach. Rather than look for job candidates with experience in either social welfare work or finance, Los Andes hired college graduates with essentially no work experience and then trained them to be microfinance loan officers committed both to the social mission of the organization and to effective operations. The idea was that without social-based or profit-based experience, employees would find it easier to adhere to the hybrid mission. Although this approach constrained the rate of growth at first, it proved to be more sustainable. Later, BancoSol changed its hiring and socialization strategies and adopted an approach closer to Los Andes’.6

Los Andes’ strategy of hiring inexperienced people and socializing them into a hybrid organization work environment may not always be ideal for early growth, but many hybrid entrepreneurs we have studied adopted this approach. For example, Adive, a French nonprofit that aims to transform the workforce of French corporations by connecting them with ethnic minority suppliers and entrepreneurs, has adopted the same strategy. “In the hybrid space, it is often easier to work with junior people who have no preconceptions as to what the job entails,” explains co-founder Majid El Jarroudi. “They can be trained to do the work, while embracing the social mission and the need to have effective operations.”

No matter which hiring approach they choose, hybrids face the additional challenge of designing compensation systems, tasks, and governance policies that reinforce an organizational culture committed to both social mission and effective operations. Los Andes, for example, developed an incentive system for loan officers that tied pay to the number and quality of the loans in their portfolios. The quality criteria used were meant to ensure that the pursuit of the social mission would remain Los Andes’ priority.

The Future of Hybrids

In the aftermath of the 2007-08 economic crisis, the global economic system is still regarded as broken. Calls for reform have been particularly strong among youth. Vast unemployment, ballooning debt, and entrenched inequality have left a generation of young people frustrated with modern capitalism and motivated to change it. Among the voices for reform, hybrid entrepreneurs are opening the way for a reformulation of the current economic order, combining the principles, practices, and logics of modern capitalism with more inclusive humanitarian ideals.

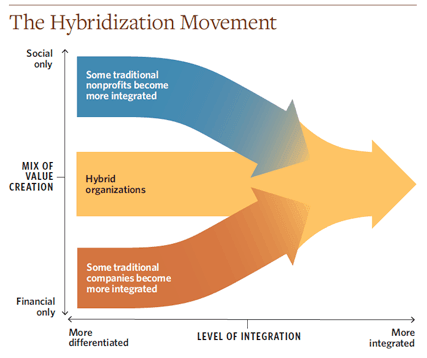

The essence of this movement is a fundamental convergence and reconfiguration of the social and commercial sectors, from completely separate fields to a common space. (See “The Hybridization Movement.”) Hybrid organizations that are currently being created serve as a testing ground, and we expect that the most successful models will be replicated (see yellow arrow in the graphic). Yet hybrid entrepreneurs are not the only actors through which the hybridization of the economy is happening. Existing for-profit and nonprofit organizations are also part of this trend.

Using the guideposts of value creation and strategic integration, one can map the movement of organizations from the commercial and social sector toward more integrated hybrid forms. Whereas corporations’ social programs were once primarily philanthropy, fully differentiated from business core, many are moving toward the adoption of more integrated social responsibility programs, in which the creation of economic and social value are coupled (see orange arrow in the graphic). Similarly, many nonprofit organizations continue to seek ways to adapt their existing models to generate some revenue to be less dependent on donors (see blue arrow in the graphic).

We expect this hybridization movement to be slow and gradual, as existing organizations are already embedded in models and stakeholder networks that constrain major strategic change. For full hybridization to occur, for-profit and nonprofit organizations and hybrid entrepreneurs need resources that align with their goal of creating both social and economic value. Hybrid organizations will require innovations in legal status, professional training, and capital financing, so that they do not need to make constant trade-offs between social and economic goals. At the field level, a critical step will be the development of measurement and reporting systems that recognize both social and financial value. The development of this ecosystem will not be the work of any heroic individual or organization; rather, it will require the creation of new systems by elected officials, policymakers, social impact investors, educators, and consumers who lift up a generation of hybrid organizations and their managers.

We are not suggesting that all nonprofits should seek profits. Some critical solutions to social problems will never be commercially viable, and it is important that we continue supporting these through grants and subsidies. Nor do we believe that all corporations are likely to become fully integrated hybrids. But for many entrepreneurs, integrated hybrid models offer a promising vehicle for the creation of both social and economic value. Someday, we may look at the advance of hybrid organizations as an early step in a broad reformulation of a current economic order, which for all of its successes has left many disenfranchised. Hybrid organizations offer a bold, sustainable infusion of humanitarian principles into modern capitalism. Yet, as with all sweeping social changes, success will require leadership and persistence. The promise of hybrids is very real, but much work lies ahead.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by John Walker, Cheryl Dorsey, Julie Battilana & Matthew Lee.