(Illustration by iStock/Feodora Chiosea)

(Illustration by iStock/Feodora Chiosea)

Universities are a critical part of innovation ecosystems, but most measures of innovation assess their impacts in terms of doctoral students, scientific publications, patents, and the commercialization of technology. Why should we neglect the potential of universities to create value through social innovation? The UN Sustainable Development Goals—sometimes called “the world’s to-do list”—include gender equality and human rights, which, in turn, are linked to many of the other goals. By harnessing research and human capital towards inclusive innovation, universities have the potential to drive massive advances in social, economic, and environmental development.

At Ryerson University, the Diversity Institute (DI) works in partnership with diverse stakeholders to use research, deep knowledge of innovation processes, and talent to advance diversity and inclusion in employment, politics, health, education, and community. Since 1999, the DI has advanced practical strategies to drive change, for example, by shedding light on barriers faced by diverse groups (considered a “best practice” by the Ontario Human Rights Commission) and developing evidence-based solutions to drive change. The United Nations Global Compact named DI a best practice among business schools for its work translating research into action to leverage innovation processes to drive inclusion.

Working with other academic partners, government, private sector, and community partners, DI uses a systems approach to address barriers for underrepresented groups and, in turn, to improve social outcomes and support economic growth. Informed by the Critical Ecological Model, the organization focuses on understanding societal, organizational and individual factors that create systemic inequality in order to develop, apply, and evaluate innovative approaches to advancing inclusion.

This analysis informs the work to address barriers at the societal, organizational, and individual level. For example, DI research informs the development of laws which shape as well as reflect values as well as combatting stereotypes in the media. At the organizational level, DI has developed tools to build organizational capacity for advancing diversity and inclusion in employment, in corporate and non-profit leadership, and in the delivery of social services. Finally, acknowledging the role of the individual in creating broad societal change, DI focuses on strategies to build individual capacity to drive change. The ecological model allows DI to bridge ideological and theoretical divides which typically dichotomize structural change and individual agency.

Research to Effect Policy Level Change

DI’s approach to enhancing inclusive innovation requires organizational and government leadership that reflects the diversity of the country’s population. Numerous research projects have exposed the lack of diversity in corporate and government leadership, in academia, and in the media. For example, DI’s DiversityLeads project, a multi-year research project, collected data in Toronto and Montreal between 2011 and 2019, benchmarking and assessing the progress of women and racialized people in senior leadership positions and boards of directors across six sectors, through an intersectional lens. Progress has been made, but massive gaps remain: in Toronto, for example, where close to half the population is racialized, white women outnumber racialized women by 10:1 on corporate boards. Among 300 corporate board members, only 4 percent were racialized and only one individual was identified as black.

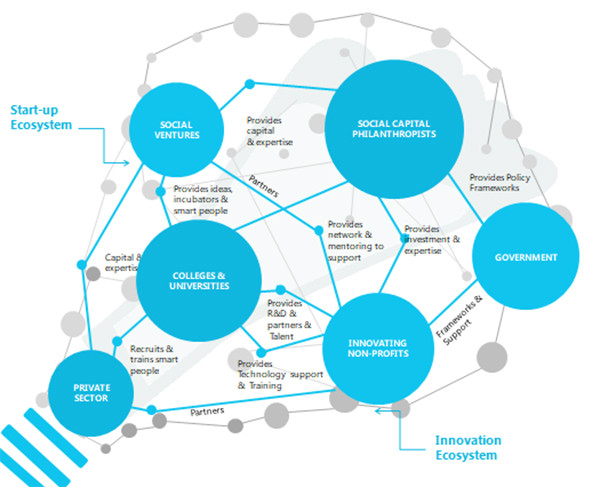

The Social Innovation Ecosystem (Courtesy of Ryerson Diversity Institute)

The Social Innovation Ecosystem (Courtesy of Ryerson Diversity Institute)

Strong data from projects like DiversityLeads supported efforts to change legislation including Bill C-25, which was passed in 2018, requiring federally-registered companies (55 percent of corporate Canada) to publicly disclose diversity on their boards, create a diversity strategy and set targets, or explain their noncompliance. Initially, C-25’s proposed regulations only required mandatory reporting on gender, but DI demonstrated that other groups were even more excluded and argued that the new law was an opportunity to advance other underrepresented groups, including racialized minorities, Indigenous peoples, and persons with disabilities, as required by Canada’s Employment Equity legislation. As a result of DI’s advocacy, the regulations were amended to include a definition of diversity and requiring disclosure of information to shareholders on at least each of the four designated groups.

DI research has also helped make space for inclusion by challenging definitions of the entrepreneur: as part of the Women Entrepreneurship Knowledge Hub (WEKH), DI research showed that equating “entrepreneurship” with Silicon Valley icons like Jobs, Zuckerberg and Dorsey (Apple, Facebook and Twitter founders) not only excludes women and marginalized groups, but shapes programs and policies which in turn do not serve them. For example, women are majority owners of only 15.6 percent Small Medium Enterprises but comprise 38 percent of self-employed Canadians. Most programs to support entrepreneurs, including those designed to support economic recover post COVID 19, focus on SMES with employees with the unintended consequence of excluding women. By raising these structural issues, work by DI showed the gaps in supports and services in critical areas. During the COVID-19 outbreak, women entrepreneurs were also far more affected by the crushing burden of additional child care and homeschooling and there can be no recovery without addressing these issues. Insights into such structural issues have also informed DI’s work with immigrant, indigenous, and Black entrepreneurs.

Building Organizational Capacity

DI also develops the tools to help organizations advance diversity and inclusion across the value chain. For example, the DI’s Diversity Assessment Tool (DAT) provides a comprehensive organizational analysis that moves beyond mere representation, looking at leadership and strategy, performance metrics, culture, operations, R&D, marketing, outreach, and more. The DAT informs DI’s consultation with major organizations across sectors, including, most recently, diversity analyses of Ontario’s Innovation Ecosystem and of the Canadian sport ecosystem in collaboration with Canadian Women and Sport. By connecting diversity and inclusion to organizational goals and strategies, DI has helped lead significant changes across sectors.

Reimaging the role of the University in driving social change is a critical mandate. One of DI’s most successful projects was the Ryerson University Lifeline Syria Challenge (RULSC), which was developed in response to the Syrian refugee crisis: by harnessing the power of students, the charitable status of the University, and its expansive network of faculty partners and other institutions, the RULSC created a crowdsourcing platform initially targeted at raising funding and volunteers to privately sponsor 10 refugee families. Within four months it mobilized 1000 volunteers, raised $5 million, and secured commitments to privately sponsor 100 refugee families, along with providing them support with housing, employment, and social opportunities. A key takeaway from this work, and from the enormous support from other universities and organizations, is the great capacity of the university to leverage its people, its infrastructure, and its influence to take responsive humanitarian action and create social value.

Action-Research Supporting Individual Capacity

Because systemic inequality exists at all levels of society—macro-, meso- and individual—the responses must all levels. Supporting structural and organizational change is therefore a critical part of driving systems change, but so is supporting individual agency and capacity. To this end, research by DI has challenged assumptions about the “skills gap,” which often leads to a focus on upskilling or reskilling job seekers. DI’s research, by contrast, reveals the barriers and biases that lead organizations to ignore talented individuals such as internationally educated engineers, computer scientists, and physicians who have high rates of unemployment and under-employment.

DI is also challenging assumptions about pathways to success and the preoccupation with Science Technology Engineering and Math (STEM) training, using evidence to suggest that social and emotional intelligence, or “soft skills,” are often equally critical to job success. Among its many initiatives, DI has created the Advanced Digital and Professional Training Program (ADaPT), an employer-centered work-integrated learning program designed to bridge skills gaps by offering alternative pathways to help youth and diverse groups transition into employment. Now in its sixth year, ADaPT has trained over 600 new graduates, with 88 percent successfully placed in internships, and dramatically improving employment prospects particularly for arts and social sciences students and graduates. ADaPT has also shifted employer perceptions about needed skills and hiring practices.

In a similar vein, the Newcomer Entrepreneurship Hub (NEH) and the Women’s Entrepreneurship Hub (WE-Hub) address employment barriers faced by immigrant and women entrepreneurs by providing experiential learning opportunities, resources and mentorship to help them start and grow their own businesses and develop transferrable skills for employment. Led by diverse entrepreneurs and experts in a supportive environment, the programs offer free access to language training, childcare, transportation and other wrap-around services to remove common barriers to accessibility for vulnerable groups. Ongoing surveys offer continuous feedback from the participants to improve the program, but also serve to inform service providers on best practices for creating programming for their clients. The results have produced a model that is being replicated and adapted across the country.

Lessons Learned

DI’s experience emphasizes the importance of bridging theory and practice, and of recognizing that research excellence and relevance are not mutually exclusive. By harnessing innovation models of change, entrepreneurial approaches to identifying and exploiting opportunities, and leveraging the assets of post-secondary institutions, DI has demonstrated how to translate research on diversity and inclusion into practice. Some of the principles and approaches can be applied across university departments and research institutes, and have broad applications to stakeholders beyond the education sector, including governments and non-profit organizations as well as individual entrepreneurs:

1. Define goals, objectives, and strategy based on evidence and an understanding of systems. All DI projects rely on rigorous research and a strong theory of change, grounded in the ecological model and ongoing evaluation.

2. Have a plan but be prepared to pivot; try, iterate, and try again. Action-research and community-based projects require agility and innovation. Universities can be highly bureaucratic, but critical to DI’s success was a “strategic action” orientation characterized by clear vision and defined goals, while being prepared to adapt and pivot to changing contexts. Key to this success is DI’s ability to obtain external funding through entrepreneurial action, while leveraging cross-sector partnerships to gain support and communicate the value of our approach to senior administration within the university. The RULSC project was created in less than an hour and had commitments to sponsor hundreds of refugees while other institutions were still in meetings to plan their response.

3. Create a “coalition of the willing” rather than consensus. When it comes to creating meaningful change, there will always be opposition, but it is necessary to identify allies in this type of advocacy work. For example, despite resistance by various stakeholders to DI’s call to expand the requirements of Bill C-25, we brought together like-minded groups and individuals who shared a commitment to change that was inclusive of racialized and Indigenous groups, persons with disabilities, and other excluded populations. Success with legislative change in Bill C-25 hinged on bringing more than 30 diverse organizations to the table in support of the DI brief. This was also key to DI’s success in developing the proposal for the $260 million Future Skills Centre as well as the $8.6 million Women Entrepreneurship Knowledge Hub. These projects required bringing together more than “the usual suspects” and leveraged decades long relationships with businesses and community organizations.

4. Leverage Design Thinking approaches to focus on user need. Seek to understand the users, challenge assumptions, and clearly define and redefine problems in order to develop effective responses. For this process to be effective, we have to be clear about who the users are and make it easy for them to participate. For example, with the RULSC project, while the focus was to support refugees, engagement of sponsors was also critical to the project’s success, so input from sponsors regarding their challenges with the process, as well as ideas from volunteers was constantly collected and implemented throughout the project’s development.

5. Create an entrepreneurial culture, which means pursuing goals with an eye to the resources available. Avoid bureaucracy which, in contrast, requires waiting for desired resources to be at hand. Bureaucracies tend to be conservative, resist change and value tradition and rules. They value plans, accountability and compliance. Entrepreneurs have a bias towards action, pivot as necessary, ask forgiveness, not permission, and are focused on results. DI embraces entrepreneurial values, processes and culture by identifying diverse opportunities, from industry consultations on Diversity and Inclusion, to undertaking major government-funded projects such as the WEKH and the Future Skills Centre. As a result, DI raises more than 99 percent of its operational funding. Experience shows that timing is not just important, it is often everything.

6. Embrace new technologies but recognize it is not a panacea. Building sharing platforms has been critical with many DI projects. DI partners with Magnet, an advanced AI-enabled digital platform which links one million job seekers and more than 100,000 employers, allowing DI to build critical mass and scale quickly. Finding innovative ways to apply technology in support of job seekers and entrepreneurs has been critical, but equally so has been the research that informed these applications. We learned through our extensive research on future skills and the “skills gap” that connecting with skilled workers was a major challenge for employers, while new graduates often lacked connections in their industry. We leveraged our partnerships along with Magnet technology in order to develop a platform that serves these specific needs, while also offering training through ADaPT to enhance the skills of these jobseekers.

7. Track, evaluate, and share results. Being entrepreneurial does not obviate accountability. Tracking results with strong feedback loops is critical to being able to pivot and adapt. Throughout all our programs, such as the NEH and WE-Hub, we gather continuous feedback from participants. Throughout the 12-week program, we administer surveys after each NEH and WE-Hub class and track participants’ progress as business owners even after the course is complete. This constant feedback has allowed us to improve the program with each new cohort, adding new wrap-around services as accommodations are requested and further develop educational content according to what works.

While more has been written on the insights from each of the cases, the overarching lessons really surround the importance of ensuring the inclusion of diverse groups across all steps in the process of innovation, and at all levels. Beyond that, the Diversity Institute is an important case to show the opportunity for educational institutions to embrace their mission as drivers of social innovation, harnessing the knowledge, the talent, the credibility and massive resources they have to address social issues, including the need for diversity across the innovation ecosystem.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Wendy Cukier & Erica Wright.