(Illustration by iStock/PeopleImages)

(Illustration by iStock/PeopleImages)

As I scan the ideas-for-good sprawled across tabs on my computer screen—from a mobile grocery store to solve food deserts to a mental health app to encourage kids processing trauma to an app to connect the incarcerated with loved ones and families—the job of whittling down the applicant pool gets much harder because of the single-most problematic assumption so many of them make: that a single enterprise at scale will solve a massive social issue.

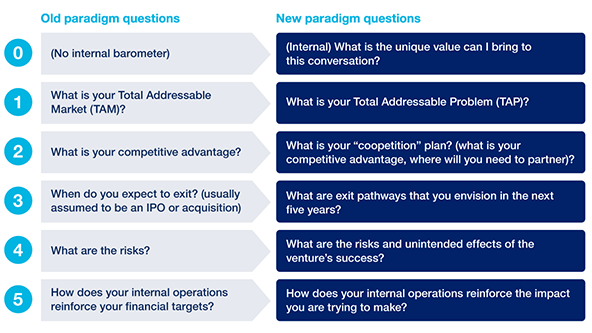

For years, social enterprise pitch competitions have operated the same way: Submitters present their world-changing idea and judges ask them standard questions rooted in a venture capital model. People too often conflate scaling impact with scaling enterprises. When we evaluate social ventures, why would we port over the Silicon Valley venture capital lens which incentivizes bigger, better, faster when positive impact may not always have this intent. As a pitch competition judge of social enterprises, incubators, and accelerators, I’ve seen hundreds of these ideas over the past five years, and nearly all of the social enterprise pitch competitions I’ve participated in apply a “grow fast, make money” model in the questions they ask: How well does the venture understand the problem, target customer, and market opportunity? How well does the solution uniquely address a problem or need in the market? How well does the venture have a competitive advantage? What is the traction made thus far?

These questions only make sense if we’re trying to incentivize scaling an organization. But doesn’t creating sustainable social impact require a different model than a Silicon Valley venture? After all, no single organization can solve global social problems. It will take a coordinated effort across sectors from social ventures to policymakers to local social service providers.

What if the pitch format used different judging criteria to promote scaling the venture and the impact itself? I know there are others out there that are thinking the same way, and as judges, we hold the power to change the rules of the game.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

A Call for a New Judges’ Playbook

If scaling impact—rather than the enterprise—is the goal, there are five must-ask questions that I recommend for my fellow judges. But take note, social entrepreneurs: These are also the questions you should be prepared to answer. Let’s use that first business idea I was asked to evaluate—a mobile grocery store to solve food deserts in blighted neighborhoods—and put this new model into practice.

0. (Internal) What value can I bring as a judge? Judges should constantly question the expertise they bring to an evaluation. I’m not an expert on food deserts, but on this panel, I was the lone business-oriented social impact practitioner, so I offered insight into the complexities of gentrification and affordable housing—alongside healthy food access. The voice of lived experience is crucial to exploring social impact and must be part of any judging panel. Moreover, those in the position of power have an imperative to use their voices responsibly and make room for the right voices to be heard.

1. What is your “TAP” (Total Addressable Problem)? A typical panel will ask about the Total Addressable Market (TAM), essentially “what’s the market opportunity?” But when it comes to impact projects, we should first ask if the venture truly understands the social problem and how it is evolving, something like the Total Addressable Problem (TAP): the magnitude of the problem being addressed and its interlocking causes. Ann Mei Chang, former Chief Innovation Officer at USAID and author of Lean Impact, asks it beautifully, “Are we falling in love more with the solution or problem?” In the case of food deserts, there is limited access to affordable and nutritious food in a given urban locale. Providing access to a new food source is a good start, but how will cooking, preparing, and consuming this nutritious food have a positive health impact on community members? What ways are the venture changing habits for people not used to eating healthier? Know your TAP, and then we can talk about solutions.

2. What is your “co-opetition” plan? If successful social ventures know how to compete, they also know how to cooperate toward scaling impact. Part of the complexity of solving social issues are the numerous actors within the solution landscape. When it comes to mobile food delivery, after all, competitors and collaborators abound. But while VC-based models might only look at the competitor side—and only see businesses like Peapod or AmazonFresh—a venture that’s truly trying to solve food deserts will find a whole suite of collaborators to consult and coordinate with: urban farmers who can provide the healthy produce, nutritionists who know how to change diets, policymakers to incentivize healthier food options, financing actors such as SNAP, food market purveyors and organizers, community health workers, and, of course, consumers and customers.

3. What are your exit pathways? Exits—whether by acquisition, a mezzanine round, or an IPO—signal the market that an organization has reached a certain level of financial sustainability and scale. While exits, as such, rarely happen in the social venture space, it’s no less important to understand what victory markers an entrepreneur can hang his or her hat on when the venture achieves significant milestones in revenue, profit, market validation, and, of course, impact. While a venture capitalist declares victory when the venture no longer needs to produce more value, an impact funder can declare victory when the social problem is solved or there has been significant headway made, done in a sustainable way; an impact “exit” could be when a venture becomes extinct. Social entrepreneurs should think about the different pathways to achieve scale, from acquisition, closing down, or influencing policy changes, in addition to making a profit. In the case of solving food deserts, this may mean not just creating versions of a Peapod solution, but also influencing policy and wrapper services that incentivize the transition to healthier eating behaviors. Scenario planning with different future end-states are important for ventures to consider and for funders to press social ventures to think about thoughtfully.

4. What unintended effects might success have? If the food desert solution requires a mobile delivery component, will that exacerbate traffic, congestion, and pollution? We must ask what broader effects the solution will ultimately have on the problem? Will it lead to new ones? Strong social ventures that work on complex problems will know the importance of a systems view. What if Facebook had had the foresight in its early days to anticipate their position as a seeming arbiter of truth? Preparing for future scenarios is important for any organization, but to claim a positive impact, ventures need to create net positive social outcomes. As judges, we have a unique role in asking these types of questions to ensure that we’re seeing the cascading effects that solutions have on a broader system not just how to fund a potential “unicorn.”

5. How do your internal operations reinforce the impact you intend to make? For today’s social ventures, the values that underpin operations must be established and reinforced early. Is the mobile grocery store venture, for example, hiring local community members that can contribute and reinvest back into their own communities? What sourcing decisions will they make that reinforce the impact they want to make? Does this also mean investing in and supporting a pipeline of urban farmers even if it means smaller margins in the short term? Evaluating the operations of social ventures now comes with more skepticism than it did before. Take the initial criticism of TOMS around its buy-one, give-one model that has now shifted to integrate into existing nonprofit programs instead of distributing it on their own: Consumers are much more savvy and won’t be enamored just by the claim of impact, but want to know that impact is being achieved well and authentically. These are important questions ventures need to wrestle with up front before they can be successful, acquire venture-backed money, and establish a brand.

Upping the Game for Both Judges and Social Entrepreneurs

As judges and impact investors adopt more sophisticated language and understanding of the social impact space, we should also be incentivizing ventures that understand these aspects. I’ve already seen the sea change start to happen at Georgetown University and the how groups like the Global Human Development Program has partnered with the Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation to incentivize students to think along this new paradigm to solve the world’s ills: rewarding ideas with expansive problem definitions, ensuring that ventures identify partners who hold key expertise to solve the problem, and encouraging other scaling levers including policy changes.

The change is coming. The next time I go to a “Shark Tank”-style social enterprise pitch competition, I hope we’ll have better-trained “sharks” that know how to ask and how to push our social entrepreneurs to think smartly about their ventures—ones that truly scale positive social impact.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Nate Wong.