(Illustration by Guido Scarabottolo)

(Illustration by Guido Scarabottolo)

To become more effective, nonprofits and foundations are turning to various sources for advice. Some look to experts who can share knowledge, research, and experience about what works—and what does not. Others turn to crowdsourcing to generate ideas and even guide decisions about future directions or funding.

Experts and crowds can produce valuable insights. But too often nonprofits and funders ignore the constituents who matter most, the intended beneficiaries of our work: students in low-performing schools, trainees in workforce development programs, or small farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. In bypassing the beneficiary as a source of information and experience, we deprive ourselves of insights into how we might do better—insights that are uniquely grounded in the day-to-day experiences of the very people the programs are created for.

Why don’t we place greater value on the voices of those we seek to help? Why don’t we routinely listen to our most important constituents?

Well, we listen a little. On site visits, funders talk to participants in the programs they fund, but these are largely staged events and hardly represent a systematic solicitation of beneficiary responses. Some nonprofits survey those they seek to help, but the quality of these surveys is typically poor. There are usually no benchmarks against which to compare results, so it is difficult to interpret the information and improve performance.

It isn’t that we don’t care about beneficiaries. They are, after all, why programs exist and why funders provide support. They are why those of us who work to solve tough social problems are inspired to work hard each day.

Perhaps we don’t really trust the beneficiaries’ point of view. Maybe we’re fearful of what they might say—that without the benefit of “expertise” they might be misinformed or wrong. Perhaps we’re scared that we will learn something that calls our approach into question. Maybe we don’t know how to solicit beneficiary feedback routinely in a way that is reliable, rigorous, and useful. Or perhaps incentives aren’t aligned to value sufficiently the insights we have gathered.

In business, companies often receive a prompt wake-up call when they don’t listen to their customers—sales and profits, the universal measures of success, generally decline. In the social sector, however, we may not get timely notice if we ignore our beneficiaries. Beneficiaries have few choices. They frequently accept a flawed intervention rather than no help at all, and they often express gratitude for even a subpar effort. As Bridgespan Group partner Daniel Stid describes the incentive structure, “[Beneficiaries] aren’t buying your service; rather a third party is paying you to provide it to them. Hence the focus shifts more toward the requirements of who is paying versus the unmet needs and aspirations of those meant to benefit.”1

This distorted power dynamic makes it more important for social sector leaders to seek and use the voice of the beneficiary. In this article we provide examples in education and health care where the perspective of beneficiaries is systematically solicited and used to guide program and policy decisions. In describing these promising cases, we look at the value of that information and what makes it useful. We also consider the challenges to beneficiary feedback that are specific to the social sector, recognizing that beneficiary feedback alone is not the answer.

We believe that listening to beneficiaries is both the right and the smart thing to do. Beneficiary perceptions are an underdeveloped source of information that can improve practice, leading to better outcomes. This isn’t a mere assertion on our part: a growing body of research demonstrates the link between beneficiary perceptions and beneficiary outcomes.

Early Rumblings

Even in business, where the consequences of not listening to customers can be quick and brutal, rigorous focus on customer perspectives is relatively new.2 Jamey Powers, son of J. D. Powers, explained a few years ago that in the auto industry, it took some time to make the customer’s voice part of the industry standard. J. D. Powers started by surveying the customers of one company, and in time, other companies saw the wisdom of such a systematic approach. It now seems that every industry—airlines, hotels, and retailers—is benchmarking customer opinions about products and services through online surveys.

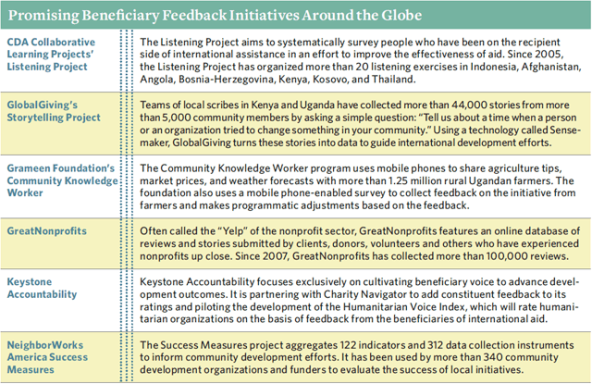

There are signs that the nonprofit sector is on a similar trajectory, both domestically and internationally. Keystone Accountability and GreatNonprofits are two organizations that were recently founded to bring the perspectives of beneficiaries to the fore. GreatNonprofits, for example, operates like Yelp, providing a way for beneficiaries and others to share stories and feedback on their experience with a nonprofit. (Disclosure: one of the authors of this article is a member of GreatNonprofits’ board of directors.) This kind of outlet for beneficiaries to provide impressionistic feedback is important and a useful complement to the systematic tools and approaches we profile here. These organizations remain small, but their mere existence and the growing number of efforts under way offer hope. (See “Promising Beneficiary Feedback Initiatives Across the Globe,” below.)

When it comes to more rigorous approaches to beneficiary feedback, the greatest advancements have been in education and health care. Health and education nonprofits often have more resources than organizations in other social sectors (such as homelessness or workforce development); have well-defined and easily “captured” populations, making survey administration easier; and are under pressure (from regulators, the media, and sometimes for-profit competitors) to produce better results.

Colleges and universities have for decades used rigorously collected student survey data to guide improvement efforts. Increasingly, we see interest in using student survey data to assess and improve high schools and middle schools as well. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, for example, has funded efforts to solicit beneficiary voice in both its domestic education work and its global health and development work. (Disclosure: the Gates Foundation was the initial funder of YouthTruth, an initiative that the authors of this article led.)

Other foundations have also sought to include beneficiary perspectives in their assessments, but they remain more the exception than the rule. A survey of foundation CEOs by the Center for Effective Philanthropy (CEP) found that 27 percent of responding foundations include beneficiary opinions in their assessments. Those that did so report a better understanding of the progress that their foundation is making strategically and a more accurate understanding of the impact the foundation is having on the communities and fields in which it works.3

How Beneficiary Feedback Can Be Used

There are three distinct points in a program’s life when one can systematically solicit the perspectives of intended beneficiaries:

- Before | When we are designing a program or initiative, incorporating the beneficiary perspective can help us understand their needs, preferences, interests, opportunities, and constraints.

- During | When a program is under way, rapid feedback loops that solicit the beneficiary viewpoint can help us adapt quickly.

- After | Once a program concludes, understanding beneficiary experience as part of a rigorous inquiry helps us determine whether a program worked and why or why not.

Our focus in this article is on the “during” stage—obtaining the perspectives of beneficiaries while they are receiving services or participating in a program—because this is the stage that is most often overlooked.4

The Voice of the Student

Five years ago, the three of us launched an initiative to help funders, schools, school districts, and education networks hear from their intended beneficiaries: high school students. The Gates Foundation was interested in understanding how students were experiencing the schools it was funding and asked CEP to create a program to collect and analyze student perceptual data.

In the design stage—guided by a national advisory board that included education leaders, researchers, youth development practitioners, media experts, and a high school student—we analyzed existing efforts. We were surprised to find that, although a variety of student surveys existed, few seemed to be helping leaders in their decision-making. Many were poorly designed and lacked comparative data, making it difficult to understand what was a good rating on any given question. And most lacked good systems for sharing data with district leaders, principals, or teachers to inform their decisions.

Students we spoke with expressed skepticism—if not downright cynicism—about the surveys. In focus groups during our design phase, students repeatedly said they doubted that anyone really cared about their views, or that survey results would be taken seriously. They rarely saw any data come back to them from the surveys they had completed.

On the basis of our analysis, we saw an opportunity to do something better. We created a program called YouthTruth. Beginning with a pilot program at 20 schools in 2008, YouthTruth has gathered feedback from approximately 142,000 students from 28 districts and networks across the United States. The project solicits students’ opinions about their comprehensive school experience—including relationships with teachers, school culture, student engagement, perceptions of academic rigor, and preparedness for the future.

YouthTruth was designed to emphasize comparative data, so leaders could easily understand the relative strengths and weaknesses of particular schools and programs. The YouthTruth model shares data in understandable ways: in-depth reports, individualized conference calls to discuss results, and access to an online library highlighting how other schools have used YouthTruth feedback.

YouthTruth has spurred significant changes by participating schools. Some schools have revamped curricula in response to the results; some have instituted new disciplinary, mentoring, and student advisory processes; and others have reallocated personnel time. One school principal explained, “When we started this process, we thought this was just going to be another district-run student survey. We have never been able to use the data we have received in the past from our student surveys…. I didn’t realize YouthTruth would be so action-oriented. This data is incredibly helpful.”

That focus on student perceptions as a force for continual improvement is what motivated the Aldine Independent School District in Houston to participate in YouthTruth. The district—with 64,000 students, 84 percent of whom are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch—won the Broad Prize for Urban Education in 2009. Despite its strong performance, school leaders wanted more data and they wanted to hear more directly from students. All but one of Aldine’s 11 high schools participated in the survey in 2011-12, and 73 percent of students completed the survey. Houston Endowment picked up the tab.

The YouthTruth findings showed numerous opportunities for improvement. The districts’ schools tended to rate lower on school culture—questions like whether students agree with statements that “most students in this school treat adults with respect,” that “most adults in this school treat students with respect,” and that “discipline in this school is fair.” There was a wide range of differences in ratings of high schools, and district superintendent Wanda Bamberg noted that these differences tended to correlate with differences in academic achievement. District leaders are now using the YouthTruth results to guide their planning. Individual schools are drawing on the data in campus decision-making, from revisiting a discipline management plan to augmenting staff development programs and improving two-way communication with students.

Aldine is hardly alone. An independent evaluation by researchers from Brandeis University found that 98 percent of school leaders who have participated in YouthTruth had used—or planned touse—YouthTruth data to inform specific changes at their school. In a more recent survey of repeat participants, 92 percent of school administrators agreed that they had used YouthTruth to make specific programmatic or policy changes at their schools.

YouthTruth’s data collection and administration efforts—using online surveys and encouraging schools to make the survey a significant event in the school—have resulted in high response rates, averaging 76 percent in all participating schools. YouthTruth’s emphasis on comparative data requires that the core survey instrument be the same in all schools, but it was found that most questions have equal relevance regardless of context or geography—although the interpretation of results might differ. Districts and schools can add custom questions to get at specific concerns they feel are not sufficiently covered in the core survey.

An important design element of YouthTruth is its emphasis on obtaining authentic student responses and closing the loop with students. YouthTruth emphasizes the importance of candor and reassures students that their confidentiality will be protected. YouthTruth also helps students understand that the survey results will influence change. MTV produced a video that schools can use to introduce students to YouthTruth. As the MTV personality Carlos Santos puts it, “usually you take a test and your teachers give you feedback. Well, this time, it’s the other way around. You’ll be grading them.”

Participating schools pledge to share results with students. Gaining a commitment from schools to report back to students isn’t just to demonstrate respect for the time and thought students put into completing the survey. It also makes it more likely that school leaders will act on the results.

For YouthTruth to make a difference in schools and districts over the long haul, it needs to be repeated at regular intervals. The overwhelming majority of participating schools plan to repeat, and many already do so annually. About half of the participating schools in the 2011-12 academic year were repeat users. This repetition allows school leaders to gauge progress and helps create a culture in which student voice is valued.

Student perceptions can complement other academic measures, such as test scores, in assessing school performance. Research has demonstrated that there is a relationship between student perceptions and outcomes. Not only can students discern who is an effective teacher, but better student experiences—as reflected by selected student perceptions—have been associated with more positive academic outcomes. A YouthTruth module takes feedback to the level of individual teachers, giving school leaders an invaluable way of identifying teachers who are stars and teachers who need support.

Although YouthTruth has created positive change, the project remains relatively small, covering just a fraction of the approximately 25,000 US secondary schools. Skeptics continue to wonder whether student perceptions can be trusted. Currently, there are only fledgling system incentives to help elevate student perspectives from a “nice to have” to a must-have continuing measure of performance.5 And finding funding for YouthTruth has proven difficult, as cash-strapped districts are limited in what they can pay, and the education-focused philanthropic community has been slow to embrace beneficiary feedback as a funding priority.

The Voice of the Patient

K-12 education remains a nascent field for beneficiary perceptions. In contrast, health care benefits from some well-developed systems. In 2001, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a seminal report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,” which highlighted six important tasks for improving the US health care system. Among them was a call for care to be “Patient centered—providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”

The IOM report prompted a movement in the health care field to measure the patient’s experience of care—and for the providers to use those data to improve the patient experience. This movement grew out of considerable research showing that improved patient experiences are directly related to better health outcomes. When patients have better communication with providers, and when they understand treatment options and feel that they have some say in their own care, they are more likely to follow a treatment regimen and improve their health.6

Not only did the IOM report underscore the importance of patient-centered care, it also recommended aligning payment policies with quality improvement. This alignment became part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; private and public insurance and reimbursement schemes now include targets for measuring patient experience during hospital stays. Initially, the targets simply prescribed that hospitals collect data to measure patient experience, but in 2013 they will include specific goals for the quality of patient experience.

Hospitals now use a number of measurement tools in this effort. Chief among them is the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), which is intended to measure patients’ objective experience of care, not just their subjective satisfaction. The HCAHPS is a 27-item survey administered to a random sample of recently discharged hospital patients. The survey asks, for instance, about the nature and quality of a patient’s communication with his physician and nurse, a patient’s understanding of treatment options, and whether a patient felt treated with respect. All told, the core survey asks about 18 aspects of the patient experience.

Many hospitals have collected information on patient satisfaction for internal use, but until HCAHPS there were no common metrics or national standards for collecting and reporting information about the patient experience. Since 2008, HCAHPS has allowed valid comparisons to be made among hospitals locally, regionally, and nationally.7 As of May 2012, the nationally benchmarked HCAHPS was being used by 3,851 hospitals, with 2.8 million completed surveys. Summarized data are also publicly reported so that consumers can be better informed in their choice of hospitals.

“The patient experience is important,” says Dr. James Merlino, chief experience officer at the Cleveland Clinic. “We set a goal and a standard of 90 percent (patients having positive experiences with all aspects of their care) and we drive to it, sharing feedback throughout the system, down to the local units. When we started this journey several years ago, some of our units were not doing well—less than 10th percentile nationally. We have made impressive progress by continuously sharing data and holding our managers and leaders accountable.”

The Cleveland Clinic used the patient feedback to implement “purposeful rounding,” whereby nurses check in with each patient every hour during the day and every two hours at night, to see how the patient is doing. This approach not only helped the Cleveland Clinic reach the 90th percentile in its HCAHPS scores, it also resulted in greater efficiencies. Because patients are assured that a nurse will visit them regularly, they have stopped using the call button as much as before, allowing the nursing staff more time for quiet, uninterrupted treatment planning.

Clinics that serve low-income people, who are often not commercially insured, have a more difficult time obtaining patient feedback. Perhaps patients who are poor and on public assistance don’t trust the system or are afraid that any critical comments might jeopardize the care they are receiving. Or perhaps the clinics themselves do not view what the patients think as a priority. Even though these safety net clinics, as they are called, are mandated by the federal government to get patient feedback, there is no set standard for doing so, no uniform reporting is required, and no resources are provided.8

The California HealthCare Foundation (CHCF) has spent many years trying to improve the patient experience in safety net clinics throughout California, simultaneously trying to help clinics lower costs and improve health outcomes. CHCF recently supported a study of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey and other patient surveys to determine the best method for soliciting feedback from patients in safety net clinics.9 Overall, the surveys were disappointing and underscored the challenges of reaching this population. Beneficiary response rates ranged between 14 and 36 percent, too low to generate much confidence in the results. There were multiple reasons for the low response rates. Literacy was an obstacle, especially for the long CAHPS survey. Limited access to computers and the Internet, both within and outside of the clinics, also constrained efforts to collect data. And the clinics had difficulty generating accurate lists of patients to survey.

Challenges Ahead

Although we believe that rigorously listening to beneficiaries is powerful, there are, as we have seen, several significant challenges to this work.

It’s expensive | Reaching beneficiaries can be expensive and time-intensive. Schools and hospitals provide controlled environments, with significant resources, in which it is relatively easy to reach people. Even with these advantages, the cost of delivering a YouthTruth survey and playing back results to a school is several thousand dollars per school. We are working hard to drive down those costs without compromising rigor or quality, but it isn’t easy. For human services organizations, where the beneficiaries can be difficult to survey and where the budget constraints are especially severe, it’s easy to see why this work often falls off the priority list.

It’s difficult to get responses | Many intended beneficiaries lack Internet access. Others are less than fully literate, making it difficult for them to understand and respond to a survey. For many, being a beneficiary of a vital service can engender fear and anxiety and a resulting reluctance to respond to surveys candidly. We saw the cynicism in our student focus groups when we were exploring the potential for YouthTruth. Likewise, safety net clinic patients were often quite reluctant to participate in the patient surveys, possibly out of fear of reprisal.

It makes us uncomfortable | Hearing from those we are trying to help can be challenging. What if they don’t think what we do is working? What if their perspectives call into question our most fundamental assumptions? People working in the nonprofit sector are overwhelmed by demands for help and work hard to meet them. It can be difficult to then take the extra step of creating rigorous feedback loops.

Better Decisions

In health care and education, when beneficiary feedback is collected with improvement in mind, it leads to better decisions. Still, collecting and using rigorous feedback from beneficiaries remains too often the exception rather than the rule at nonprofits and foundations.

Admittedly, health care and education are easier fields in which to collect beneficiary perceptions than fields whose client population may be more transient, such as homeless shelters. But we believe that there is likely to be a relationship between the degree of difficulty in collecting the feedback and its ultimate value. That’s because the fields in which beneficiary feedback is more difficult to collect are likely to be the very areas in which the intended beneficiaries are especially lacking a voice.

There is certainly a strong moral argument for listening to the people you seek to help. Who among us would want others deciding what is right for us without being asked how we feel about it and how we are experiencing it? But the cases in health care and education demonstrate that there is also an essential effectiveness argument for hearing from those we want to help. A study recently published in American Heart Association journal demonstrated that patients’ perceptions of care, especially nursing care, predicted both the clinical quality of care and lower inpatient mortality rates for acute myocardial infarction.10

Results from education studies suggest an analogous link between student perceptions and measures of academic performance. The recent Measures of Effective Teaching study found that some student perceptual data are positively correlated with student achievement data, and in fact are more predictive than classroom observations. In another study, those schools in which students could see the connection between their schoolwork and later success in college and the workforce had lower absence and failure rates.11 Researchers at Stanford University’s John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities have completed a number of studies, soon to be published by Harvard University Press, documenting the link between student perceptions and student outcomes.12

These links suggest that beneficiary perceptions are useful leading indicators of the longer-term outcomes we seek. Leading indicators are important because they allow decision makers to make improvements while the program is under way, rather than waiting until after negative outcomes—patients dying or students dropping out—to make adjustments. Beneficiary feedback isn’t just the right thing to do; it’s the smart thing to do.

The authors wish to acknowledge the feedback we received from colleagues who commented on an earlier draft of this paper: David Bonbright, Paul Brest, Barbara Chow, Jack Fischer, James Knickman, Larry Kramer, James Merlino, Christy Pichel, Melissa Schoen, Rhonnel Sotelo, Jane Stafford, and Daniel Stid.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Valerie Threlfall, Fay Twersky & Phil Buchanan.