Many people think of social enterprises as small organizations that rely mostly on charitable gifts to operate. In fact, social enterprises are often much larger and more market-driven than thought, while still maintaining a social mission. They also play a significant role in the economies of many of the countries they operate in, according to one of the most comprehensive surveys of social enterprises ever undertaken.

In the past, many social enterprises relied on grants to fund most of their operations. No more. Today, sales of products and services are the most important source of income for the social enterprises we surveyed, making up more than half of their budgets. And they have seen these revenues without compromising the “social” part of “social enterprise.”

Not surprisingly, all surveyed social enterprises are profoundly committed to a social mission. And contrary to what many think, social enterprises are in fact enterprises, not just small businesses. In 2014, the 1,030 social enterprises we surveyed generated more than €6.06 billion in revenue, served 871 million beneficiaries, employed just over half a million people, and helped many more—roughly 5.5 million people—to find a job, making labor markets more equal and ensuring social inclusion of people with disabilities or migrant backgrounds.

These are just a few of the highlights of our recent survey of 1,030 social enterprise directors in China, Russia, Germany, Hungary, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. This survey by the “Social Entrepreneurship as a Force for More Inclusive and Innovative Societies” (SEFORÏS) consortium, conducted between April and December of 2015, is one of the most comprehensive ever conducted of social enterprises.

The cooperation of these social enterprises, combined with the financial support of the European Union, allowed us to build the most robust and largest panel database on social enterprises to date. It is unprecedented in its depth, too; on average, the social enterprise directors invested two hours of their time responding to our questions.

In this article we offer a sneak preview of the survey results. A much more detailed cross-country report on social enterprises is available, as are reports on social enterprises in individual countries.

Social Enterprises Are Businesses

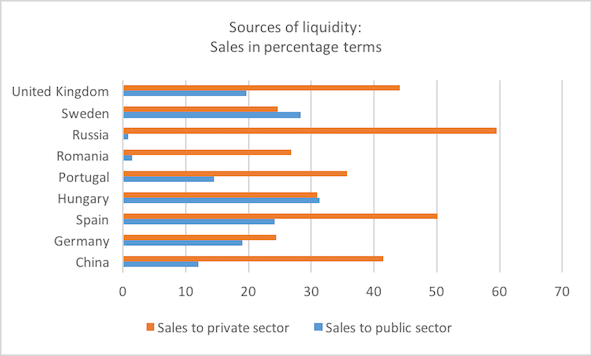

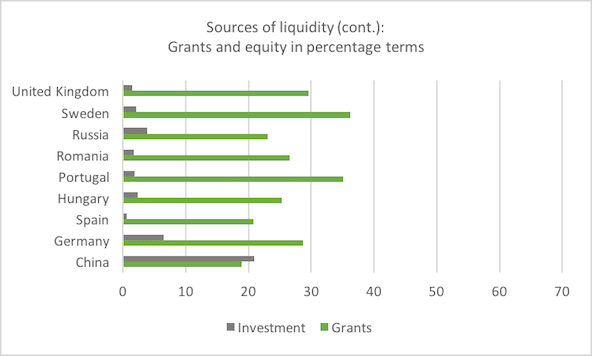

For 70 percent of the social enterprises we surveyed, selling products and services constitutes their primary operational model.1 In all nine countries, revenue generation through sales was the most important source of liquidity. The social enterprises financed on average 57 percent of their activities this way. Yet there are differences between countries: In Romania, for example, financing through grants was nearly as important as sales.

In most countries, the bulk of sales comes from selling to the private market, not to government. The exceptions are Sweden and Hungary. In Sweden, the government is not only the most important ‘buyer’ of social enterprise products and services, but also accounts for the lion’s share of grant funding available to social enterprises. In Hungary, sales to the private market are more or less on par with sales to the public sector.

In all countries, grants represent the second most important source of liquidity, accounting for an average of 27 percent of financing. By contrast, investment capital appears to play only a minor role in all countries. A notable exception is China, where equity provides 21 percent of the surveyed organizations’ financing, the majority of which is also founder-financed.

Social Enterprises Are Driven by a Social Mission

That the social enterprises in our survey are firmly anchored in the market is not at odds with their social mission. Across countries, social enterprises seek to align their social impact and revenue-generating activities in their day-to-day operations. They also report that the purpose of their organization is clearly and predominantly social.

Furthermore, most social enterprises seek to systematically assess how they perform against these social goals. About 65 percent of the surveyed social enterprises report that they track their social performance, with a high of 97 percent in Portugal and a low of 48 percent in Spain. Social enterprises across all countries favor measuring social performance by counting the numbers of beneficiaries or clients served. An exception is Sweden, where the most prevalent indicator of social performance is the satisfaction of beneficiaries or clients served.

With regard to the nature of the social issues that social enterprises address, our survey indicates that there are some social issue domains that are attractive to social enterprises in all countries. For example, social enterprises tend to be active in “employment and training” and “economic, social community development” in all countries except Russia. Similarly, social enterprises are active in “education and research” in all countries except Hungary.

Other domains are not as popular in all nine countries. Social enterprises are particularly active in “social services” in Hungary, Portugal, Romania, Russia, and the United Kingdom; in “health” in Hungary, Germany and Sweden; and on the “environment” in Russia and Spain. A distinct feature of social enterprises in China is that their activities are particularly targeted at promoting “volunteering.”

Social Enterprises Don’t Compete With Government

To our surprise, none of the surveyed social enterprise directors indicated that their government is the dominant player in their market. This suggests that social enterprises are not competing with government but rather appear to complement them. Many social enterprises appear to provide services in areas where governments have completely withdrawn, as is the case in many European countries where strict austerity agendas were implemented in response to the 2008 financial crisis.

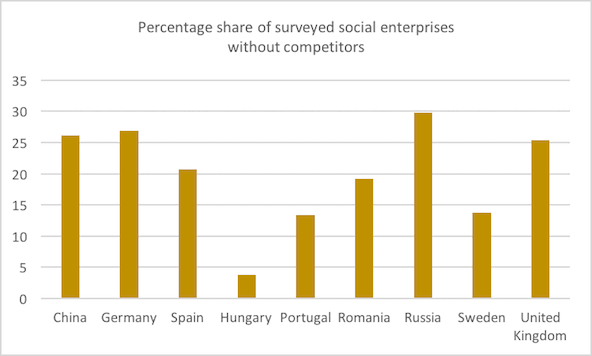

When asked what other organizations provide similar services and products to their offerings, social enterprise directors identified businesses (in China, Russia, and the United Kingdom), nonprofit organizations (in Germany, Hungary, Portugal, Romania, and Sweden), or other social enterprises (in Spain) as the most dominant type of competitor. Twenty percent of surveyed social enterprises indicated that they do not face any competition. This figure, however, masks substantial cross-country differences, from a low of 4 percent in Hungary to a high of 30 percent in Russia.

A relatively high share of social enterprises in Russia and China claim that they face no competitors. The social enterprise sector seems to be comparatively nascent in these countries, and particularly in China, where it is also changing very quickly. There, 65 percent of social enterprises were founded no more than four years ago. In Russia, the corresponding share is 43 percent, which is higher than in the other countries. But it’s not only the age of the social enterprises that is different; so is the age profile of the social enterprise directors. They are significantly younger in China and Russia than in the other countries. The average social enterprise director is in his or her thirties in China and Russia, in his or her forties Germany, Spain, Hungary, Portugal, Rumania, and Sweden, and in his or her fifties in the United Kingdom.

The Gender Gap Is Alive and Well in Social Enterprises

In China, Germany, Romania, Spain, and the United Kingdom, the majority of social enterprises are run by men (55, 55, 59, 70, and 55 percent respectively). In Hungary, Sweden, and Russia, it’s the other way around: 61, 65, and 62.5 percent of social enterprise directors, respectively, are women. This is in stark contrast to commercial enterprises, where the share of male directors (67 percent) in all nine countries is higher than that of female directors (37 percent).2 Interestingly, the way social enterprises are governed also points to relatively strong gender inclusion. Out of the 86 percent of surveyed social enterprises that have boards, only 10 percent had an all-male board.

Looking Ahead

The data we gathered comes at a critical point in time for social enterprises. It brings to the fore important trends of convergence across geographies but also intriguing cross-country differences. Our ambition is to offer an evidence base for more informed decision-making by governments, support organizations, and investors. And most important, we want to offer a resource for social enterprises to benchmark their activities and amplify their voice.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Marieke Huysentruyt, Ute Stephan & Johanna Mair.