Disheartened over the teacher-student disconnect that impeded learning in India’s mainstream public education system, a veteran educator named Elizabeth Mehta believed she had a solution: a model where teachers, teacher educators, and students learn from each other. In 2003, having developed seven women from Mumbai’s marginalized community into skilled, early childhood teachers, she and her husband Sunil Mehta launched an NGO called Muktangan, derived from Hindi, meaning “free space.”

Over the ensuing years, they launched seven municipal schools plus a teacher education center, and partnered with UNICEF to train government “master educators” who, in turn, trained more than 10,000 teachers in the state of Maharashtra.

As Muktangan scaled and the work of managing the NGO grew, the Mehtas decided to gradually transition out of day-to-day leadership. They recruited three separate executives in succession, in an attempt to find a new leader for Muktangan. For different reasons, all three amicably departed.

The Mehtas have now turned to building a senior team from within the organization and coaching its members to lead, as it is this team that shares Muktangan’s values and vision. They have identified a promising individual from the team, who will ultimately take the NGO’s helm. “If Muktangan is going to sustain and expand, it can no longer be led just by us,” says Elizabeth Mehta. They just had to find the right leader.

The Mehtas’ story is not uncommon. Their conundrum—how to let go of an organization they brought to life and successfully transition to a new leader—extends across much of India’s social sector. Our research reveals that widespread doubts persist about whether NGOs and funders have done enough to develop the leaders who will replace the sector’s first-generation pioneers.

Gaps in Leadership Development

In part, the sector’s misgivings stem from a growing recognition that many Indian NGOs overly depend on a single leader, often the founder. A recent Bridgespan Group survey of approximately 250 NGOs (to the best of our knowledge, the first data-driven study of NGO leadership development in India) revealed that founder dominance runs deep. Founders are engaged with about 88 percent of NGOs launched more than 20 years ago and have remained at the helm (as “founder-leaders”) of more than a quarter of these organizations. And founders are involved in 99 percent of NGOs launched between 11 to 20 years ago. Yet these founder-leaders do not often think about the next generation; 50 percent of the surveyed NGOs do not have any leadership succession plans in place, and more than 70 percent of NGOs lack a succession plan even for their senior-most leader.

Diving in further, we probed a set of exemplar NGOs profiled in the Stanford Social Innovation Review article, “Why Indian Nonprofits Are Experts at Scaling Up,” which spotlights 20 organizations that have extended their reach to millions of constituents. With an average tenure of 22 years, founders currently lead—in title or in practice—65 percent of them.

Like the Mehtas, some of the pioneering social entrepreneurs who launched NGOs a decade or two ago are beginning to relinquish their spot at the peak of the organization’s pyramid. Those who are contemplating a transition or have recently done so include: Madhu Dasa, who gave up the CEO post at Akshaya Patra, which he founded in June 2000; Dipak Basu, who conceived Anudip in 2005 and recently brought on an executive director to begin managing the NGO day to day; Matthew Spacie, who founded Magic Bus in 1999, attempted to bring in a successor for several years and recruited Jayant Rastogi as the CEO in 2016; and Vishal Talreja, who launched Dream a Dream with 15 others in 1999 and remains as chief executive, but restructured the organization in part so he could relinquish some of the decision-making.

Given the long tenures of some NGO founders, the pace of turnover will likely accelerate in the coming years. The next generation of leaders will soon have to fill the vacuum. But according to our survey and more than 50 follow-up interviews,1 they are ill-equipped to do so. More than half of the surveyed NGOs do not feel confident that anyone internally could effectively lead the organization in the absence of their senior-most leader.

“Most leaders do not strive to develop leaders,” says Megha Jain, an associate director at the strategic philanthropy foundation Dasra. “Many acknowledge [the need] when pointed out, but do not think about it as a primary part of their job or prioritize it against other urgent, day-to-day deliverables.”

Evidence that Indian NGOs are failing to put a premium on developing leaders includes:

- NGOs have not prioritized time and resources toward investing in promising talent. Some 53 percent of the polled executives do not believe their organization is capable of developing effective leaders—a candid yet eye-opening concession.

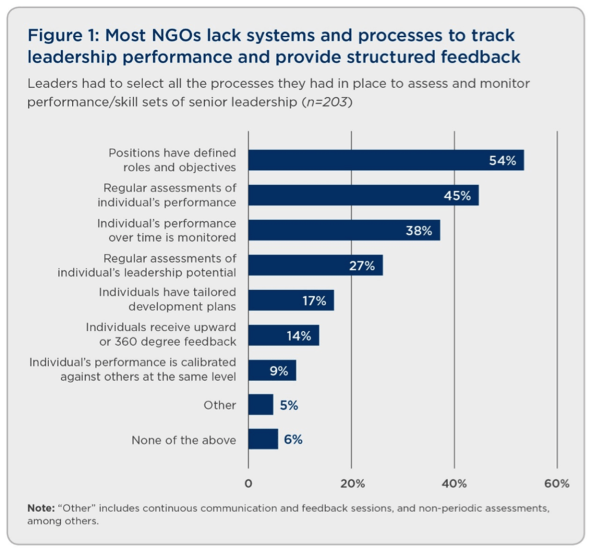

- NGOs lack systems to track senior leaders’ performance and provide structured feedback. Just over half of the surveyed NGOs have defined the roles and objectives for their senior positions; fewer than 40 percent monitor senior leaders’ performance (see below). Thus, leaders do not have the opportunity to identify and address the gaps in their skill sets.

- There’s a paucity of opportunities for people with promise to grow, as just 54 percent of NGOs provide even informal coaching and mentoring. Additionally, more than 60 percent of NGOs are unaware of the paltry number of external leadership development programs in India.2

Even basic systems for monitoring performance are rare among Indian NGOs. (Image by Alison Rayner)

Even basic systems for monitoring performance are rare among Indian NGOs. (Image by Alison Rayner)

The result: India’s NGOs lack a deep bench of homegrown leaders who can support the pioneer at the top and step up when that person leaves. The implications threaten these organizations’ ability to sustain and scale impact, at the very moment when stakeholders’ expectations of impact are climbing. Funding flows into the social sector are escalating, driven by the rise in individual philanthropy and corporate social responsibility contributions. Funders and NGOs themselves are demanding better and bigger results. If India’s NGOs are to make real strides toward ambitious goals such as providing equitable healthcare, ensuring high-quality education for children, or providing access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation, they will have to confront the unassailable fact that exceptional organizations rely on exceptional leaders—and they need to grow more of them.

Barriers and Building Blocks

Fortunately, NGOs recognize they need to fill this talent gap, and take on the challenge of cultivating homegrown leaders who will support and succeed the pioneering founders. A full 97 percent of survey respondents say leadership development is vital to their organizations’ success, a belief echoed by funders. And some NGOs are already taking replicable steps to grow their in-house leadership talent. Their experiences, gleaned from interviews and secondary research, identify the building blocks for surmounting three critical barriers to developing leaders: underinvestment in a foundational culture, irregular leadership needs assessment, and anemic leadership development practices and systems.

Barrier 1: NGOs lack a foundational, leadership development culture and often do not have a shared understanding of what this should look like. Pushed in part by donors to focus almost exclusively on delivering programs, NGOs do not emphasize talent development and often shortchange themselves by under-investing in people. In our interviews, several NGO leaders struggled to articulate what “leadership development” means. They associated development primarily with training programs and sending leaders to conferences.

Building block: Starting at the top, NGOs need to build a culture where leadership development is everybody’s business. It takes dedicated founder-leaders to define and grow a culture that nourishes the next generation. Those who commit to the challenge hold themselves accountable for their own and others’ development. The ideal is for people at every level to feel confident enough to champion learning, the first step to leading.

One such organization that has started down this path is Smile Foundation. Launched in 2002, Smile Foundation takes a holistic approach to driving social change by focusing on child education, family healthcare, employment enhancement, and women’s empowerment. Today, the NGO reaches 400,000 children and their families in urban slums and villages in 25 Indian states.

The organization’s Empowering Grassroots initiative aims in part to build leadership capacity in community-based organizations working in villages and slums. Building on the same theory, Smile Foundation’s model seeks to empower employees at every level by ensuring that decision-making is decentralized at the level of the regional director, manager, or team closest to the issue. Because decision-making is pushed to the front lines, more people can build skills through on-the-job experience. “Leadership is not associated with position and power,” says Amit Prakash, senior manager of research and program development. “Anybody can play that role.”

Even as Smile Foundation works to put more authority in the hands of employees through their daily work, it also cultivates additional learning opportunities to increase the odds that people grow and make better decisions. Leaders encourage senior managers and people with particular skill sets to informally mentor junior staffers and stakeholders. At the same time, the organization has implemented specific mechanisms to help people build skills together. For example, it participates in an initiative called Change the Game Academy, which combines online courses and face-to-face coaching on project management, communication, and local fundraising. And groups within Smile Foundation, such as the Project Approval Committee, give emerging leaders the opportunity to step outside their daily responsibilities and think about challenges confronting the entire organization.

Finally, Smile Foundation has rolled out a 2017-2018 work plan that seeks to build employees’ ability to innovate and lead. As part of that effort, it will put in place succession plans for current leaders, beginning with the chief operating officer, who hopes to identify a successor in the next three to five years. In this way, Smile Foundation’s executives begin to build pathways for next-generation leaders.

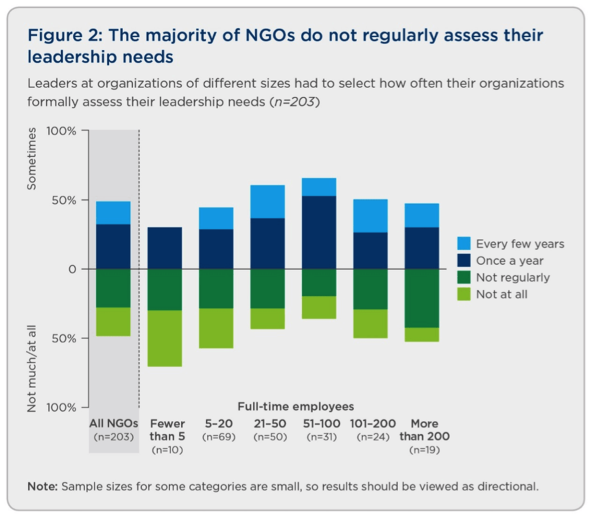

Barrier 2: NGOs do not assess their leadership needs on a regular basis, especially in the context of meeting future challenges and seizing opportunities. Fifty percent of NGOs surveyed said they do not formally assess their leadership needs on a regular basis, including 22 percent who do not assess their leadership needs at all (see below).

Few NGOs regularly assess their leadership needs, even larger NGOs. (Image by Alison Rayner)

Few NGOs regularly assess their leadership needs, even larger NGOs. (Image by Alison Rayner)

Building block: NGOs need to map leadership development needs and adapt as the organization scales. Organizations get a higher return on leadership investments when they target the white space between their current base of skills and their future challenges. Founder-leaders (like other senior leaders) at high-performing NGOs define the organization’s goals and then determine the skills required to achieve them. This allows them to meaningfully measure their leaders’ performance and future potential, and plan for any gaps. Importantly, they do not cling to the organization’s leadership model; rather, they adapt it for the future.

Consider the Bangalore-based, Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship & Democracy, which seeks to improve the quality of citizenship and infrastructure in India’s cities. The NGO, which has 115 full-time employees, focuses on civic learning, civic participation, and “city-systems” reforms. Since the organization launched 16 years ago, its founders have constantly reassessed and reinvented its leadership structure to better confront emerging challenges. The NGO’s leadership model has so far undergone three major iterations:

- Janaagraha 1.0: Originally from India, Ramesh Ramanathan and Swati Ramanathan had high-flying careers in the United States, in finance and in urban planning and design, respectively. On their return to India, they launched Janaagraha in 2001. Over the next four years, they took on the gamut of foundational tasks, from building programs to managing the minutiae of running a startup.

- Janaagraha 2.0: By 2005, the Ramanathans realized the organization would have to professionalize its operations if it were to extend its reach. “The organization was in mission-mode and not organized in a formal structure,” recalls Sapna Karim, head of civic participation. “We were running with large numbers of volunteers and very few staff.”

Seeking to backfill the gaps in Janaagraha’s operational expertise, the founders recruited private-sector executives with deep experience in areas such as finance, IT, and marketing. They then installed a five-member management committee to steer the organization. The move pushed the second-line leaders to step up and take full responsibility for all of Janaagraha’s operations, not just their individual portfolios. In that way, the organization’s “bench” learned to lead by doing.

- Janaagraha 3.0: Although the lead-by-committee model helped Janaagraha grow through its adolescence, decision-making could not keep pace with the organization’s expansion. “It was great to have collective ownership,” says Karim. “But there had to be a first among equals.”

In 2016, the Ramanathans decided to augment the committee with a chief executive, but with one stipulation: The CEO had to come from within. It would take too much time for an external recruit to learn to navigate the complexities of managing Janaagraha’s programs. Together, the senior leaders selected Srikanth Viswanathan, then-coordinator of advocacy and reforms, to shepherd Janaagraha into the future.

Janaagraha also engaged the consultancy Aon Hewitt in a year-long effort to help it become a learning organization (as outlined in Peter Senge’s book, The Fifth Discipline). The endeavor, led by the NGO’s founders, involved using focus groups, case studies, and various assessment tools to examine Janaagraha’s current leadership team and design for the future. Next, CEO Viswanathan wants to roll out an organization-wide performance competency framework developed with the help of a senior executive volunteer from the Tata group.

Barrier 3: NGOs lack processes, systems, and practices for developing leaders. While on-the-job “stretch” experiences can be powerful, founder-leaders do not systematically plan for them or ensure they meet development needs. Nor do they supplement these experiences with formal programs that build leadership knowledge and skills. Underlying causes for today’s ad-hoc development practices include insufficient resources (both funding and tools), low awareness, and lack of prioritization.

Building block: NGOs need to provide opportunities tailored for high-potential talent that make leadership development an everyday habit. Founder-leaders who successfully build homegrown leaders do three things well: track and assess the performance and potential of second-line executives and managers, provide constructive feedback, and deliver learning opportunities customized to each individual’s development needs. These organizations understand that leadership development works best when such tasks are woven into a formal process, which helps build a culture of continuous learning and improvement.

And yet, even though the vast majority of survey respondents say that leadership development is vital to their future success, more than half concede they are incapable of grooming the talent within their own ranks—an extraordinary waste of human potential. A notable exception is an NGO called Make A Difference (MAD).

Launched in 2006, MAD mobilizes 4,250 young leaders to seek better outcomes for roughly 3,400 children annually in shelter homes that extend across 23 cities. MAD’s holistic range of interventions includes academic support, life skills, emotional health, and transition readiness.

MAD transitioned to a dual leadership model in 2014, when an external advisor, Rizwan Tayabali, joined founder Jithin Nedumala as co-CEO. Together, the CEOs set a tone of collaboration and learning for the organization. MAD’s second line is comprised of directors (akin to division heads) who serve as the core decision-making team and mentors for the next level, the regional managers. Directors are expected to think like chief executives, and regional managers are encouraged to think like directors. The logic: Get people to look beyond their functional roles and take on more responsibility for the organization’s outcomes. For example, managing revenue streams is not just the finance team’s problem. “All of us,” says Tayabali, “are responsible for money in and money out.”

MAD has created a suite of explicit, low cost practices to help directors grow leadership skills, including:

- Competency Planning Session: Once a year, directors meet individually with Tayabali to discuss their life goals and long-term aspirations for contributing to the social sector. They then work backward to determine what skills and experiences the directors can gain at MAD to bring their dreams to life.

- Competency Day: Once a quarter, each of MAD’s directors gives a TEDx-style talk on a topic such as “how children learn” or “care practices in shelters.” The talks are live-streamed via Facebook to the entire organization. The benefit goes two ways: Directors build subject-matter expertise, while the organization expands its collective knowledge on relevant issues.

- Culture Meet: Every Thursday at 5 p.m., all the directors engage in group activities to address one of four areas in a rolling cycle: building competencies through shared learning, bonding as a team, reflecting on personal goals, or advancing the organization’s culture.

- External Learning: Once a year, MAD brings in external partners to hold a two-day workshop on personal development for directors. As funding for external learning is limited, the organization instead frees up dedicated time for people who want to pursue skill-building courses on platforms like Coursera or +Acumen, all the way up to multi-year, part-time MBA programs. In return, people share what they have learned with the rest of the organization, reinforcing a culture of continuous development.

MAD is already seeing results such as more efficient decision-making and clearer alignment around goals. Thus, Tayabali and Nedumala are pushing leadership development practices further out into the organization—to regional and city managers, and even its sprawling network of young leaders.

How Funders Can Help

For all of this leadership development innovation, neither Smile Foundation, Janaagraha, MAD nor any other NGO can fully empower its next line of leaders and transition from pioneering founders on its own. Funders have a critical role to play, especially around supporting grantees and building an ecosystem around leadership. However, fewer than 30 percent of NGOs report that funders are involved in their leadership-building efforts, and more than 50 percent of survey respondents report that their organizations have received zero funding to develop leaders over the past two years.

As Aparna Sanjay, executive director at Social Venture Partners India, concedes, “Even large grantmakers insist on funding only projects. We all need to make more strategic investments for organization building … such instances are very few and far between.”

Funders’ focus on tangible outcomes is understandable; we all want to see social change investments benefit constituents. But when funders hold back on investing their influence and resources in general operating support for “good overhead” like leadership development, they undercut the very processes that can sustain and scale NGOs over the long term.

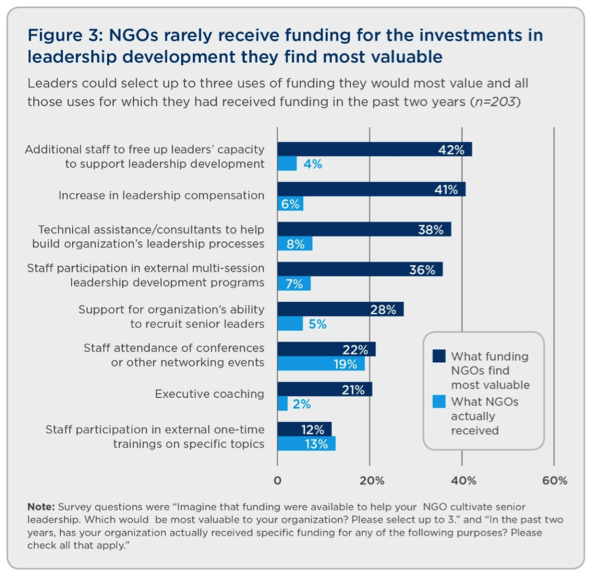

Funders can do far more to help founder-leaders at NGOs develop homegrown leaders. They can start by providing financial resources and expertise to help grantees build their leadership benches. That means “paying what it takes”—ideally through unrestricted funding or capacity-building investments tailored to grantees’ specific needs—to build leadership capacity (see below). They can also add incentives to their grantmaking, by including specific requirements for developing leaders.

Money catalyzes efforts to build effective leaders; so too does knowledge. Funders also have a vital role to play in connecting NGOs to relevant expertise, whether though formal networks such as Social Venture Partners, or through direct referrals to external experts in areas such as leadership and fundraising.

And yet, it is not enough to focus solely on individual NGO founders. The challenges are too vast. There is a yawning need for funders to help build the entire ecosystem for leadership development in India, by investing in sector-wide supports and articulating a value proposition that spurs action.

Funders can invest in developing external training programs customized to the specific needs of senior Indian NGO leaders, and in particular founder-leaders, as opposed to the broader approach that many programs take. Funders can also develop tailored resources akin to the +Acumen initiative, launched in 2012, which features a range of free or low-cost, online courses covering such topics as adaptive leadership and storytelling.

Funders can do much more to tailor leadership investments to each NGO’s needs. (Image by Alison Rayner)

Funders can do much more to tailor leadership investments to each NGO’s needs. (Image by Alison Rayner)

Equally important, funders can make the case for developing homegrown leaders and communicate it across the sector. A critical first step is to build an evidence base that spotlights the “return” on leadership development investments. They can also communicate the necessity—and the urgency—of cultivating the next generation.

In an essay published in BloombergQuint, Amit Chandra, a leading philanthropist and managing director of Bain Capital, delivers an unequivocal message: “With [the increased] level of financial capital available [to NGOs], it is imperative that we invest in human capital that is capable of handling much larger flows [of finance] with greater impact and accountability … If we apply the same approach that we have in building companies towards the development sector, I believe we can make much better progress in solving India’s social sector problems, because a lack of funding is no longer a problem.”

The Path to Building a Bench of Homegrown Leaders

NGOs and funders across India are increasingly recognizing that no founder, no matter how pioneering, can keep pace with the needs of a growing organization. Like the Mehtas, more and more pioneering founders are opening their eyes to the fact that as organizations scale, so does their complexity and the array of problems to solve—a challenge for any solo leader to navigate. Yet in most organizations, this recognition has not translated into action.

Because NGOs and funders have not adequately addressed the challenges and constraints of cultivating leaders, the result is too often the same: A pioneering founder takes on most of the decision-making, without nurturing a strong second line. Thus, the next generation of NGO leaders is ill-prepared to amplify the sector’s achievements and overcome the country’s challenges. That is not a formula for long-term success.

Moving forward, the sector will require two things: a shift in mind-set, so as to make leadership development a priority, and concerted effort by all stakeholders. Founder-leaders of NGOs like Smile Foundation, Janaagraha, and MAD offer practical, real-world approaches to developing the next generation of leaders from within. But their ideas and insights are starting points, not blueprints others should dogmatically follow. Ultimately, it is up to each organization and its funders to explore and test what works, and invent their own best practices for cultivating tomorrow’s leaders.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Pritha Venkatachalam & Danielle Berfond.